Book Excerpt: A Brand New Ballgame: Branch Rickey, Bill Veeck, Walter O'Malley and the Transformation of Baseball, 1945-1962

Chapter 21: California.

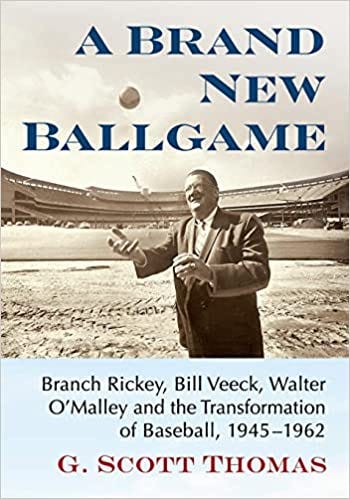

Most of the works celebrated in this book excerpt series are historical studies, and I’d argue that all of them are more compelling than your typical U.S. History 101 or Western Civ. With number 17 in the series, I am pleased to recommend one such work, “A Brand New Ballgame: Branch Rickey, Bill Veeck, Walter O'Malley and the Transformation of Baseball, 1945-1962,” by G. Scott Thomas (McFarland, November 11, 2021, $17.99 Kindle, $34.99 Paperback).

While I hope you’ll buy and read every one of the 496 pages of “A Brand New Ballgame,” fans of the Dodgers, Giants and the old Pacific Coast League will be especially interested in chapters 19, 20 and 21. I have chosen the particularly juicy “Chapter 21: California” to excerpt today. It begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.

Part III: 1958-1962. Chapter 21: California.

The Dodgers and Giants had fallen out of the pennant race by Labor Day 1957. Brooklyn was nine games behind Milwaukee; the Giants were twice as far back. Both teams were playing out the string, leaving plenty of time for Horace Stoneham to pay a quick visit to his adopted city, and for Walter O’Malley to conduct simultaneous negotiations on both coasts.

Stoneham hustled in and out of San Francisco within twenty-four hours in late August. He inspected the proposed site for the Giants’ new ballpark on Candlestick Point, met with Mayor George Christopher, and sparred with the local press. “Things are magnificent,” he told the reporters. They asked skeptically if he had spent much time at Candlestick, which was known for its stiff and chilly breezes. “Your native San Franciscan is used to this weather,” Stoneham said dismissively.

O’Malley, meanwhile, continued to play one city against the other. The Brooklyn Sports Center Authority was a dead letter — everybody agreed on that — so he revived his original plan. The Dodgers owner met with New York deputy mayor John Theobald on August 26, again proposing to build his own ballpark if the city would quickly condemn twelve acres at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush. He estimated that the stadium would cost the Dodgers $21.5 million ($197 million as of 2020). City Hall’s reaction was muted. “If Mr. O’Malley’s offer aroused city officials here, it is not immediately apparent,” wrote Bill Becker in the New York Times.

Robert Wagner, who was up for reelection in November, had feared a huge outcry against the departure of the Giants and Dodgers, but New Yorkers were surprisingly apathetic. The anticipated flood of letters, phone calls, and telegrams never materialized. The mayor shrugged his shoulders when a reporter asked if the baseball issue seemed politically dangerous. “Not particularly,” he said. This nonchalance trickled down to his staff. “If we find that O’Malley and Stoneham are dead set about leaving New York,” said William Peer, Wagner’s executive secretary, “then we’ll just have to pick up our marbles and go home.”

Robert Moses did not share this indifference. He reacted to the latest stadium proposal with an unalloyed blend of annoyance and contempt. O’Malley had once again stressed his love for Brooklyn, which greatly irritated Moses. “I have heard this speech over and over again ad nauseum,” the czar moaned. “From time to time, Walter has embroidered it with shamrocks, harps, and wolfhounds, and has added the bouquet of liqueur Irish whiskey.” Moses’s anger was accentuated by O’Malley’s dismissal of the stadium site in Queens, which the latter considered unsafe. “What Walter says about foundation problems at Flushing Meadow is rubbish,” Moses said.

O’Malley was also negotiating with Los Angeles officials as August turned to September, much to the displeasure of those closest to him. His wife and daughter emphatically opposed a coast-to-coast move, as did a majority of the Dodgers’ front-office employees. Buzzie Bavasi never forgot a staff meeting where O’Malley asked for a show of hands. “The vote was eight to one not to go to California,” he said, “but the one vote was Walter’s.”

Most of the men in uniform were unhappy, too. “If you’d have asked the players on the Dodgers to take a vote, it might have been 25-0 to stay in Brooklyn,” pitcher Don Drysdale recalled in 1990. Center fielder Duke Snider remembered two years earlier that he had been “heartsick” at the prospect of moving. Their emotions were especially notable because both of these future Hall of Famers had been born in Los Angeles.

But Drysdale was wrong about unanimity. A third Dodger destined for Cooperstown, Brooklyn native Sandy Koufax, thought it might be fun to live somewhere different. “I have to confess that, Brooklyn boy or no, I was rather looking forward to another adventure,” Koufax later wrote. Contemporary newspaper accounts suggested that he wasn’t alone. The Los Angeles Times reported in 1957 that Drysdale (“why all the stalling?”) and Snider (“most of the fellows can hardly wait”) were especially eager to head west, regardless of their memories three decades later.

Yet their fates remained uncertain as O’Malley continued to prod New York officials and dicker with their Los Angeles counterparts. He seemed to be making no discernible progress until September 10, when tycoon Nelson Rockefeller unexpectedly declared his desire to save the Dodgers for New York. “Certainly the greatest city in the world should have two baseball teams,” said Rockefeller. “It has proved that it can support them.”

This was a game changer. Rockefeller was one of the richest men in America, so wealthy that he could have paid for a stadium himself. The mayor of Los Angeles all but surrendered. “If it is true that Mr. Rockefeller has entered this picture, I’m very much afraid we don’t have much of a chance to get the Dodgers,” Norris Poulson said disconsolately.

Rockefeller had never been a sports fan — he directed his passion toward his massive art collection — but it was an open secret that he intended to run for governor of New York in 1958. Professional politicians considered his plans absurd. How could such a blue blood possibly connect with the average voter? Rockefeller confided his political dreams to a former three-term governor, Thomas Dewey, who slapped him on the knee. “Nelson, you’re a great guy,” Dewey laughed, “but you couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in New York.”

That’s where the Dodgers came in. Rockefeller’s chief aide, Frank Jamieson, pushed him to intervene. “Most politicians have to build themselves up. You’ve got to bring yourself down,” Jamieson said. Here was an opportunity to grab a few headlines and appeal to the workingmen who loved the Dodgers. “You don’t have to buy the team,” Jamieson said. “You just have to make a bid, to show your interest.”

The next nine days brought a whirlwind of publicity. Wagner, Rockefeller, and O’Malley huddled for more than two hours on September 18 to hammer out the final details of their secret proposal. O’Malley offered only three words — “it has merit” — to reporters who pushed for details. But there was widespread dissent when the plan was unveiled the following day. Rockefeller wanted the city to condemn the Atlantic-Flatbush site, then sell the property to him for two million dollars. He, in turn, would lease the site to the Dodgers, rent-free, for twenty years. The team would have the right to buy the land at any time.

James Lyons, the Bronx borough president, expressed the majority view. “There is no great need to subsidize the Dodgers,” he said. Rockefeller quietly exited the stage — his political profile having been greatly enhanced by all the front-page play — and the momentum shifted back to Los Angeles.

The time inexorably came for New York’s teams to say goodbye. The fate of the Dodgers had not yet been announced, but it was assumed that their Tuesday night game against the Pirates on September 24 would be their farewell to Brooklyn. Only 6,702 fans bothered to show up. Ebbets Field organist Gladys Goodding played tunes appropriate for the occasion: “California, Here I Come,” “After You’re Gone,” “Don’t Ask Me Why I’m Leaving,” “Thanks for the Memories,” and “How Can You Say We’re Through?” She capped the 2-0 victory over Pittsburgh with “Auld Lang Syne.”

The Giants wrapped up their forty-seven-year stay in the Polo Grounds five days later. Among the 11,606 in attendance was the widow of John McGraw, the team’s Hall of Fame manager from 1902 to 1932. Blanche McGraw came to pay her respects despite her sadness — “New York can never be the same to me” — but Horace Stoneham was curiously absent. “I couldn’t go to the game,” the owner explained. “I just didn’t want to see it come to an end.” His Giants played listlessly, losing 9-1 to the Pirates, but most fans stayed till the bitter end. They cheered loudly as their favorite player, Willie Mays, came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. “I never felt so nervous,” Mays said. “My hands were shaking. It was worse than any World Series game.” He swung wildly, hoping to salute the fans with a home run, but tapped back to the pitcher.

All eyes now turned west. The National League had set a deadline of October 1 for resolution of the Dodgers’ fate, yet O’Malley still lacked a firm offer from Los Angeles. Poulson was proposing to give 185 acres of Chavez Ravine to the Dodgers, while promising to help the team secure another 115 acres from private owners. He pledged that the City Council would vote on his package by October 7. The league unanimously granted O’Malley an extension.

Poulson’s proposal required two-thirds approval — ten of the fifteen council members — and he knew it would be a close call. The land deal was unpopular with conservative elements in Los Angeles, led by Councilman John Holland, who blasted it as “nothing but a steal and a giveaway.” The resulting meeting was predictably contentious and extremely long.

The marathon began as O’Malley watched Game Five of the World Series in Milwaukee — the very city that had inspired his desire to build a new stadium — and it droned on as he flew back to his home in Amityville on Long Island’s southern shore. A desperate Rosalind Wyman reached him by phone shortly after he walked in the front door. She pushed for a commitment that might help her to sway the council’s recalcitrant members.

“I am going to the floor,” Wyman said. “I would like to say you are coming.”

But O’Malley would not tip his hand, not even at this late hour. “Mrs. Wyman, I am grateful for everything you have done,” he said. “I am grateful for everything the mayor has done. But I have to tell you if I could get my deal in New York, I’d rather stay in New York.”

Wyman returned to the debate, saying nothing to her colleagues about the bewildering conversation. Had O’Malley made a secret arrangement in New York? Did he view Los Angeles as a mere bargaining chip? Or was he truly torn, unable to decide between his native city and the promised land? Wyman didn’t know what to think. She cast an affirmative vote when the time finally came, and nine others joined her. The 10-4 vote barely met the threshold for approval.

O’Malley remained uncharacteristically quiet the following day. It fell to the assistant general manager of the Dodgers, Red Patterson, to post a fifty-two-word statement in the World Series press room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria. The press release announced that the Dodgers would be taking “the necessary steps...to draft the Los Angeles territory,” a convoluted way of saying that they were heading west.

The agonizing decision had finally been made, and O’Malley swiftly put Brooklyn behind him. He shot a telegram to Mayor Poulson: “Get your wheelbarrow and shovel. I’ll meet you at Chavez Ravine.” And he summoned reporters from Los Angeles newspapers to his old office on Montague Street, eager to establish new relationships as quickly as he could. “Good teams and good attendance go hand in hand,” he told them. “It takes money to build a winner. Witness Milwaukee’s success. Well, the Braves can consider themselves challenged as of today.”

Robert Wagner appeared confident on the surface, yet no politician ever operates without fear. The mayor still wondered if the loss of both National League clubs might emerge as a last-minute issue in his reelection campaign. He hustled to preclude the possibility, declaring on September 26 — twelve days prior to the Dodgers’ official departure — that he would soon appoint a committee to secure a new NL team for New York.

There was no particular reaction to his announcement. Millions of local fans were experiencing a mixture of anger, depression, and grief. Their gloom enveloped the city, inspiring Arthur Daley to write a remarkably pessimistic column in the New York Times. “Will there ever again be another National League club in New York?” Daley asked in mid-October. “The answer is a vehement no.” Individual action of any sort — even as simple as political retribution against the mayor — seemed pointless.

This lethargy worked in Wagner’s favor. He crushed his Republican opponent, Robert Christenberry, by 924,000 votes on November 5. It was the largest margin of victory for any mayor since 1898’s five-borough amalgamation, and it remains the biggest to this day. Wagner ran up an edge of 331,000 in Brooklyn alone, winning three-quarters of the borough’s votes. The baseball issue had truly caused him no harm.

But some owners worried that the sport itself would not be so lucky. Phil Wrigley had loyally supported both moves —”Mr. Stoneham knows what he is doing, and what he is doing is strictly his own business” — yet he wasn’t sure it was wise to vacate the nation’s largest market. He warned his colleagues that they might have opened the door for a third major league. “I mean an independent group competing with the present leagues. Why not?” Wrigley said.

The president of the Class AAA International League was thinking along the same lines. Frank Shaughnessy announced on October 17 that the IL’s Havana Sugar Kings would relocate to Jersey City in 1958. He hailed it as “the first big step in becoming a third major league” and speculated about adding a club in Brooklyn. “I don’t know how long it will take,” said Shaughnessy. “Maybe a year, two, or five. But we are on our way.”

Ford Frick had no intention of allowing a repeat of the protracted Pacific Coast League nightmare of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Some of the International League’s markets seemed big enough for the majors — Buffalo, Miami, Montreal, Toronto — but others were way too small. The Rochester region had only 600,000 residents, Richmond just 400,000. The commissioner brusquely advised Shaughnessy to jettison his big-league dreams. The IL would not be putting a team anywhere in the New York metropolitan area — not in Jersey City and definitely not in Brooklyn.

Frick had other headaches. If two of baseball’s flagship franchises could abandon North America’s largest market, why couldn’t smaller teams indulge themselves? Calvin Griffith resumed his flirtations late in the 1957 season, even though President Eisenhower had just signed a bill authorizing a new fifty-thousand-seat stadium for the Senators. Griffith greeted a delegation from Minneapolis — “I listened intently and was happy that I sat in on the session” — and visited the city’s two-year-old ballpark after the World Series. The two sides held eight meetings before Griffith pulled the plug on October 21.

The young owner promised to restrain his wandering eye in the future, proclaiming his loyalty in an op-ed piece in the Washington Post. “This is my home,” Griffith wrote on January 15, 1958. “As long as I have any say in the matter, and I expect that I shall for a long, long time, the Washington Senators will stay here, too. Next year. The year after. Forever.” Frick applauded the sentiment, though he conceded that Washington could be a tough place to make money. “From the standpoint of baseball, it is not good to be leaving the nation’s capital,” the commissioner said. “But you have to think of the poor devil who is holding the franchise.”

It would have been unthinkable a decade earlier, but the Indians were also debating a move. Cleveland’s 1957 attendance was only 722,256 — 72 percent short of Bill Veeck’s 1948 total of 2,620,627, still the big-league record. Hank Greenberg, who had remained in the front office after Veeck’s departure, was now the general manager, and he had gone sour on Cleveland. He privately urged the team’s chairman, Bill Daley, to grab Minneapolis before Griffith changed his mind. “Our management was composed primarily of Clevelanders, and they were afraid to make the move. I was pushing for it,” Greenberg later admitted. Daley eventually had his fill of Greenberg’s agitation, firing the GM in October 1957, then buying his share of the Indians a year later.

This turbulent state of affairs — the air of uncertainty that pervaded baseball — gave hope to Robert Wagner. He appointed four men to his baseball committee on November 29 and challenged them to lure a National League team to New York. He assumed it would be a simple task.

Three of Wagner’s appointees were well-known. James Farley had been one of Franklin Roosevelt’s closest aides. Bernard Gimbel was chairman of the renowned department store that bore his name. Clinton Blume had pitched for the Giants in 1922 and 1923, and then served as president of the Real Estate Board of New York. A somewhat obscure lawyer, William Shea, rounded out the panel.

It came as a surprise when Shea was named the committee’s chairman — and even more shocking when he emerged as the point man in New York’s recruitment drive. “We are in competition with other cities now,” Shea said confidently, “but I can’t see certain National League teams resisting an offer which includes fourteen million people within thirty-five miles.”

The new chairman winnowed his list to three targets. The Braves, Cardinals, and Cubs were blessed with solid fan bases and stable ownership; they weren’t moving anywhere. That left the Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Philadelphia Phillies as possibilities. Shea approached each of them, dangling a short-term lease at Ebbets Field and the long-range prospect of a new ballpark. He believed that one of the three would shift to New York before 1958’s opening day. “I started out to get a team, and it looked easy,” he said later.

The Board of Estimate, New York’s preeminent legislative body, added weight to Shea’s pitch in January 1958, voting to build a stadium on city-owned land. But the resolution wasn’t quite as decisive as it originally appeared. It stipulated that absolutely no action would be taken until a National League club made a solid commitment. “You just can’t build a stadium on a promise,” Wagner explained, even though a city with fewer resources, Milwaukee, had succeeded by doing precisely that.

It didn’t matter in the end. The owners of the three targeted teams were unanimous in their refusal to relocate. Powel Crosley briefly feigned interest in leaving Cincinnati — “we are under no obligation to stay here” — in order to obtain more parking around his ballpark. The city quickly caved, allocating two million dollars for an additional twenty-six hundred spaces near Crosley Field. Pittsburgh’s John Galbreath refused to even discuss moving. “[I] won’t even entertain any thoughts of it,” he said. Philadelphia’s Robert Carpenter Jr. was similarly adamant. He politely sat down with New York’s representative, then he firmly said no.

This last meeting had the greatest impact on Shea, who was impressed by Carpenter’s loyalty to his city. “I begin to see that I am placing myself in the position of asking him to do the very thing I would never do. Pull out of your own town. That cured me,” Shea recalled. He resolved to find a different solution to his problem, though he knew it would take more time than he had originally expected. The National League would not be playing ball in New York in 1958.

The Pacific Coast League had no choice but to accept the National League’s invasion of its territory. Three franchises were affected. The Seals, who had been based in San Francisco since 1903, slipped off to Phoenix. The Angels, whose ties to Los Angeles dated back to 1892, shuffled nine hundred miles north to Spokane, Washington. And the second PCL club in L.A., the Hollywood Stars, crept inland to Salt Lake City.

The Dodgers and Giants agreed to pay an indemnity totaling $946,000 ($8.65 million in 2020 dollars) to be split equally by all PCL teams except Phoenix and Spokane, which were owned by the two big-league invaders. But the windfall was coupled with a demotion. The PCL was stripped of the Open classification that Pants Rowland had worked so hard to obtain in 1951. Its return to the AAA level — triggered by the loss of its biggest markets — evoked no sympathy from the baseball establishment. “This change of the baseball map has been hanging over the Coast League’s head for ten or twelve years,” said Phil Wrigley, “but its owners never did a thing about it. Baseball, in general, is that way. It never does anything until the roof caves in.”

That was a perfect description of Horace Stoneham’s management style over the years. Inaction was his preferred strategy, so he had naturally remained passive as his Giants deteriorated and the Polo Grounds crumbled. His decision to move to San Francisco shocked his fellow owners because of its uncharacteristically proactive nature. This new Stoneham — a man of surprising efficiency and resolve — remained in the forefront in the wake of the 1957 season. He swiftly made himself at home in San Francisco, accompanied by a moving van jammed with the club’s equipment and office furniture. “Personally, I’m not really missing Broadway and New York so much,” he would insist after just a few months in California.

Stoneham made progress on several fronts. He decreed that his club would remain the Giants — “we think it’s a pretty good name” — even though local fans advocated a switch to the Seals. He hammered out a deal for temporary use of tiny Seals Stadium, which had just 22,900 seats, and he approved the blueprints for his new ballpark on Candlestick Point. Contractors promised that it would be ready for opening day in 1959.

There were a couple of hitches in this generally smooth transition. Stoneham’s biggest failure in New York had been his unwillingness to promote the Giants. He sought to turn over a new leaf in San Francisco, even agreeing to speak at a baseball banquet that winter. It did not go well. Stoneham rambled incoherently, then abruptly stopped. “Some of us drink too much,” he muttered, ending his experiment in public relations. A more dispiriting episode involved the efforts of star center fielder Willie Mays to purchase a home. “I’d never get another job if I sold this house to that baseball player,” said the recalcitrant builder, who carefully left out the fact that Mays was black. The sale was eventually consummated, but only after San Francisco’s supposedly liberal orientation was laid open to question.

Yet the Giants’ move, taken all in all, appeared to be going well, inspiring the San Francisco Chronicle to brag in a January 1958 editorial. “In San Francisco, the city that knows how, the Giants are in business, flourishing and making friends like sixty,” the paper crowed. “In Los Angeles, the city that never has known how, chaos and frustration are roomies.”

The Chronicle’s jab contained a kernel of truth. Walter O’Malley and thirty Dodgers employees had landed in Los Angeles on October 23, 1957, greeted by several hundred excited fans at the airport. But the team’s arrival was far from an unalloyed success. O’Malley was served with a subpoena shortly after stepping on the tarmac. A taxpayer group had filed suit against the Chavez Ravine land swap, charging that construction of a baseball stadium did not constitute a “public purpose,” the very objection that Robert Moses had raised in New York.

That first day foreshadowed the Dodgers’ entire first winter in their new home. Every success, or so it seemed, was diluted by a subsequent failure. O’Malley stoked the enthusiasm of his new fan base — “we’re not going to be second to Milwaukee in anything” — only to be inundated with bills for moving expenses, the PCL indemnity, and leases that remained in effect for Ebbets Field and Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium. He trumpeted his impressive ticket sales — pocketing a million dollars by late November — only to learn that eighty-five-thousand citizens had signed petitions demanding a referendum on the Chavez Ravine deal. “We never had such a thing in New York,” sputtered O’Malley, who was stunned to learn that local voters would decide the fate of his dream ballpark in June 1958.

His biggest problem was simply finding a place to play for the upcoming season. Sportswriters expected the Dodgers to settle into Wrigley Field, which O’Malley had acquired when he purchased the minor-league Angels. But he turned up his nose at its puny capacity, lack of parking, and general decrepitude. It reminded him of nowhere quite as much as Ebbets Field, and he cast his veto.

Only two stadiums in Los Angeles were big enough for O’Malley. Both, however, were ovals that had been designed for football. He preferred the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, but its governing board deadlocked on the Dodgers’ application, with four members voting in favor, four against. So he turned reluctantly in December to the Rose Bowl. It had all the seats he could possibly desire — slightly more than one hundred thousand — though its location was not ideal, ten miles northeast of downtown in suburban Pasadena.

“The Rose Bowl will prove to be a happy stadium for our West Coast debut,” O’Malley declared in early January, putting the best face on an unhappy situation. But the two sides could not agree on a formal contract, and the Dodgers suddenly found themselves adrift again. O’Malley desperately gave Wrigley Field a second look, renewed contact with the Coliseum, and even floated a drastic possibility. “If anything should happen to make it impossible for us to open in Los Angeles,” he said, “we could still return to Brooklyn.”

The lengthy stadium debacle horrified Norris Poulson — “I’m sorry to say we are the laughingstock of the country” — and he finally intervened to force a solution. The mayor brought O’Malley and the Coliseum Commission together on January 17, 1958, and they managed to reach an agreement. “This ended my longest losing streak,” O’Malley joked lamely as he shook hands on the deal. Only ninety-one days remained before the season opener, and there was plenty of work to be done. Dugouts and a press box had to be built in the Coliseum, the vast territory beyond right field had to be fenced off, and a gigantic 40-foot screen had to be erected above the left-field fence, which loomed just 250 feet from home plate.

O’Malley was destined to pass into baseball mythology as the quintessential mastermind, a clever strategist who coolly planned every facet of his epic move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. But his legend did not comport with reality. The Chavez Ravine transaction — the impetus for the Dodgers’ relocation — had quickly become entangled in a lawsuit and a referendum, both of which had caught O’Malley off guard. And the team’s temporary stadium was clearly inadequate, perhaps the most absurd ballpark in the history of the major leagues.

The task of filling the Dodgers’ new home fell to Harold Parrott, the Ebbets Field ticket manager who had come west with the club. He considered the Coliseum to be a joke — he likened it to a “gigantic saucepan” — and he scoffed at any suggestion that O’Malley might be a genius. The haphazard nature of the California shift caused him to think otherwise. “The move,” he would later write, “was about as well thought-out as a panty raid by a bunch of college freshman who’d had too many beers.”

About the author:

G. Scott Thomas has been a journalist for more than 40 years, specializing in politics, demographics, sports, business, and education. His blog, Baseball's Best (and Worst), is updated on Tuesdays and Fridays at bestworst.substack.com. Thomas holds a B.A. in American history from Washington and Lee University, and currently lives in Tonawanda, N.Y., with his wife.

Can't read any history of The Move without thinking of the 300 Mexican-American families uprooted by the powers-that-be to appease the team we root for. A number of references in here to that aspect of the move, but all devoted to political machinations. Maybe i missed a mention of the human beings who lost their homes with little or no compensation. Nevertheless, every spring i'm a fan again, and the past sinks into the past.