Book Excerpt: Baseball's Brief Lives: Player Stories Inspired by the Infinite Inning

Don Drysdale, Preacher Roe, Delino Deshields and Pee Wee Reese are featured within.

With number 13 in our book excerpt series, I am happy to recommend “Baseball's Brief Lives: Player Stories Inspired by the Infinite Inning,” by Steven Goldman (Baseball Prospectus, 2022, $14.99 Paperback). An interesting volume by an equally interesting author.

I asked Mr. Goldman to explain the title, and tell us a bit about the work, and here is that explanation:

The Infinite Inning is a podcast in which I try to explore the game's past in unexpected ways, often by using it as a way to form analogies about the present. One thing I've learned from doing that exercise again and again is that there are valuable things to be learned from thousands of players, not just the handful who get into the Hall of Fame. In other words, it's not how many home runs a player hit, but who he was and what happened to him. That's where you can learn something that might change your understanding of the game, or of the broader world beyond it. (Which is not to say the numbers aren't fun too--I have plenty of them in the book.)

One way that I've tried to demonstrate that is by selecting these 100 players at random. That's also where the title BRIEF LIVES came in. There is a famous book from the 1600s that had that title, much emulated since. As I wasn't writing full biographies of these players but literally brief lives, it seemed appropriate to tip my hat in that direction. More than that, though, players, at least professionally, literally do have brief lives. Thus the title also acknowledges this reality of baseball.

That's what the book is--a collection of 100 brief lives, longer than a Baseball Prospectus player comment, shorter than a biography, in which I tried to give them reader some key story about each of the players. It's my hope that people will come away with an appreciation for the humanity inherent in baseball as well as the broad array of talents and characters that have populated it. It's all so much deeper than a Cooperstown plaque can convey.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Brief Lives is chock full of Dodgers, of which I have chosen four to share with you: Don Drysdale, Preacher Roe, Delino DeShields and Pee Wee Reese.

From Chapter One: Team of Greats.

DON DRYSDALE, RHP

518 G, 1956–69 209–166, 2.95 ERA (121 ERA+), 67.1 WAR

Imagine dying in an Edward Hopper painting. Hopper’s most famous piece is Nighthawks, his depiction of a noirish nighttime diner, but he often painted people alone, whether on trains, in apartments, restaurants, hotel rooms, or even a movie theater. Sometimes there is more than one person in the painting, but it’s clear they’re alone together, not connecting. Some of the solitary occupants of these rooms are men, and some are women. They vary in states of dress and undress, but the nudity isn’t erotic or an expression of freedom, it’s a concession to loneliness: If no one sees you, you have nothing to conceal. Occasionally, as in his Macomb’s Dam Bridge or House by the Railroad, even buildings are alienated. The bridge depicted in the former is adjacent to Yankee Stadium (old and new), but Hopper chose an angle that didn’t include that welcoming edifice. Not every Hopper painting conforms to this theme, and the painter himself liked to deny there was a theme at all, but the bulk of his work exists in the penumbra of human warmth.

After Don Drysdale retired in 1969, he stayed in the game as a broadcaster, bouncing through Montréal, Texas, Anaheim, and Chicago before finally landing back in Los Angeles. He had a wife and four children but nevertheless pursued a peripatetic life. That life no doubt had its comforts and amenities, but the vagabond’s existence has certain risks, whether one sleeps in a suite or on a park bench. On July 3, 1993, Drysdale suffered a fatal heart attack while alone in a Montréal hotel room. He was less than three weeks away from his 57th birthday.

I did a pre-game interview with him recently and I remember thinking how good he looked. How healthy and strong. I guess you never know what’s going on inside a person.

—Dusty Baker.

There are no further details to give, because the ex-pitcher was alone when he died; Drysdale had had some heart problems, and they caught up with him at a moment when aid was impossible. He saw the Dodgers beat the Expos, probably had dinner, then retired for the night. Fans take for granted the high status enjoyed by ballplayers and the other participants in major-league baseball and often use that to claim that the players owe them something— say, not striking for better pay or improved conditions, or playing through a pandemic. Never let it be forgotten that baseball is a grind, and it can exact a price from all involved, whether players, front office members, or broadcasters. They sacrifice home and family for your entertainment, and every once in a rare while, the last thing they see on this earth is the hotel minibar or the thin comfort of an alien pillow.

Drysdale still holds the modern NL record for hitting batters, with 154. “The pitcher has to find out if the hitter is timid,” Drysdale told Dave Anderson of The New York Times in 1979. “And if the hitter is timid, he has to remind the hitter he’s timid.” He picked up the philosophy from veteran pitcher Sal “The Barber” Maglie, who was with the Dodgers when Maglie was 40 and Drysdale was 19. Maglie only hit a few batters per season, though; his point was about intimidation, pushing the batter off the plate so he could drop a curve on the outside corner. Drysdale took it to an extreme, hitting up to 20 batters a season. A number of pitchers have since hit more batters than Drysdale (the closest active pitcher, Charlie Morton, has 148 (through midseason 2022) and may pass Drysdale’s total in less than half as many innings), but few of them were criticized for being headhunters, because they didn’t proselytize on behalf of intimidation like he did.

Drysdale led us in wins that year [1957]. He threw hard and he threw sidearm and he was mean enough to knock people down, but the big guy was just a kid at the time and wasn’t a smart pitcher or sure of himself…. Driz, as I called him [was] a very volatile guy. He had a hair-trigger temper. He was a good guy, but he could be as mean as [Koufax] was clean.

—John Roseboro

From Chapter Two: Names

PREACHER ROE, LHP

333 G, 1938, ’44–54 127–84, 3.43 ERA (116 ERA+), 29.6 WAR

Branch Rickey was the most important general manager of all time, but trades weren’t his strong suit. He was focused on sales because (a) his creation of the farm system gave him a massive surplus of players, and acquiring more of them wouldn’t have alleviated the problem; and (b) he got a cut of each transaction. That’s not to say he never made a great deal. It’s fitting that his best swap came as a consequence of his historic decision to sign Jackie Robinson.

Dixie Walker was a productive and popular outfielder known as “The People’s Cherce.” As his primary nom du baseball suggests, he was also a Stars ‘n’ Bars flyin’ Southerner who lived down to one’s worst expectations of bigotry, initiating a petition during spring training 1947 intended to pressure the Dodgers into abandoning the promotion of Robinson. This prompted the famous late-night meeting in which Dodgers manager Leo Durocher told the players that it didn’t matter if Robinson was “black, white, or striped like a fucking zebra,” because he was going to help them win, and that was what mattered. Walker asked to be traded. Rickey was fine with that, but he bided his time, getting one more good year out of Walker before fleecing the Pirates by sending Walker and two pitchers for Roe, third baseman Billy Cox (a weak hitter but with a sterling defensive reputation), and infield prospect Gene Mauch.

Walker was just about done, and the two pitchers didn’t work out. Roe, who was going on 32, was coming off of a two-year period in which he had gone 7–23 with a 5.21 ERA (77 ERA+). Despite being a hard thrower, weak control had kept Roe buried in the Cardinals chain for most of his twenties. World War II manpower shortages and a questionable draft status made Roe attractive to the Pirates, who traded for him. He pitched well in 1944 and ’45, but, after the 1947 season, the Pirates must have been tempted to write him off as a wartime-only player, as so many other 4-F players were. There should be a scouting award for whoever it was with the Dodgers—be it Branch, his son (“The Twig”), or some other perspicacious baseball mind—who was able to look at Roe and see that he had the capacity to be remade.

There were some mitigating factors: Roe had pitched through the after effects of a fractured skull in 1946 (a phys-ed teacher in the offseason, he protested a call while coaching a girls basketball team; the ref put him in the hospital). Coincidentally or not, Roe’s velocity disappeared along with his cranial integrity. He compensated with off-speed stuff and one of the best spitballs of his time. It would be fascinating to know if the Dodgers were aware of the spitball at the time of the trade. Roe wondered that too, not the spitball part, but why Rickey bothered to acquire him at all.

“He said he figured I had had tough luck in the last three years,” Roe quoted Rickey as saying in For the Love of the Game, “and I was gonna have a lot of good luck now and he wanted it to be with Brooklyn.” Roe’s stats suggest there was some truth to that, but maybe Rickey was talking less about poor defensive support and was thinking more of Roe’s eight-inch skull fracture. Either way, the Dodgers got one of the best pitchers of the Brooklyn years:

Roe’s peak season, on a cosmetic basis, was 1951, when he went 22–3 with a 3.04 ERA. He won his first 10 decisions through June 21. Nine of the 10 were complete games. On July 20, he started another streak of 10 straight wins, which lasted almost through the end of the season. He really peaked in 1949, when he went 15–6 with a 2.79 ERA (fourth-best in the league), walking 44 and striking out 109 in 212 2/3 innings to lead the NL in strikeout-to-walk ratio.

The Dodgers played the Yankees in the 1949 World Series. In the bottom of the fourth inning of Game 2, left fielder Johnny Lindell of the Yankees hit a comebacker which smacked Roe in his pitching hand. Roe completed the 1–3 play to retire the side. In the dugout, a blood blister formed under one of his fingernails. The Dodgers trainer drilled a hole in the nail to relieve the pressure, and Roe went back to the mound and completed a six-hit shutout.

The guys on my team used to call it “your Beech-Nut curve.”… That’s because of the gum. On the bench, between innings, I’d dig into my pocket for a stick of it, and say: “I’m gonna get me a new batch of curve balls.” I don’t know why Beech-Nut was better. There seemed to be something in it that would make the ball slicker than any other gum. If this is a testimonial, then they can have it for free…. I found out something else about Beech-Nut. It was the only kind of gum that would make the ink on a ball fade, and I think that might have been what caused it to be the best.

—Preacher Roe, Sports Illustrated, July 4, 1955

As duplicitous as he was, there was one batter with whom Roe could do little: In 178 career plate appearances, Stan Musial hit .381/.441/.688 with 12 home runs against him. “I figure it’s mostly up to Musial,” Roe said in 1951. “Of course, I try to keep him off balance and cross him up and sometimes I get him out and start thinkin’ I’ve found something. Then the next time I face him he knocks the same stuff I got him out on last time out of the park…. When he’s gonna hit you he’s gonna and there’s nothing you’re gonna do about it except refuse to throw the ball.”

I know one time I told Campanella that Stan’s father was sick, and I told Campy to ask Stan how his father was. When the inning was over I said, “Well, did you ask Stan?” and Campy said, “Yeah, but before he could answer he was on third.”

—Preacher Roe, For the Love of the Game

From Chapter Five: The Too-Short Peak

DELINO DESHIELDS, 2B

1615 G, 1990–2002 .268/.352/.377 (98 OPS+), 24.4 WAR

What the heck was that career? DeShields was taken by the Expos with the 12th-overall pick of the 1987 amateur draft. A high school shortstop out of Delaware, he turned down a Villanova basketball scholarship to sign. Rated the game’s 12th-best prospect heading into the 1990 season by Baseball America, DeShields had little in the way of home-run power, and, with a lot of swing-and-miss in his game, it wasn’t a sure thing he would hit for any kind of average. Arguing in his favor was terrific speed and a willingness to take a walk. In 1990, the Expos made him their Opening Day second baseman despite his having played only 47 games at Triple-A. He had never played second before, but they pushed him over so they could keep playing Spike Owen at shortstop. DeShields went 4-for-6 with a stolen base in his first game and didn’t look back.

More accurately, he didn’t look back for about a third of a season. DeShields was hitting .304/.398/.424 on June 15 when he was hit on the hand by Joe Magrane. A broken finger kept him idled for about a month. He hit .276/.356/.367 the rest of the way. Which was the real DeShields? He gave a troubling answer in 1991, when he hit .238/.347/.332 and led the NL with 151 strikeouts. With the laudable exception of drawing 95 walks, he did nothing well. He made 27 errors. He opened the season with 12 consecutive successful steal attempts, then was caught 23 times in 67 attempts the rest of the way.

It might have seemed safe to dismiss DeShields based on one and a half seasons of mediocre performance, but that would have been underestimating a thoughtful, determined player. He cut down the strikeouts (giving back some of the walks, as well) but recovered his batting average. From 1992–93, he hit .294/.374/.386 and stole 89 bases against only 25 times caught stealing, which made him attractive enough to the Dodgers that they traded Pedro Martinez to get him.

As then–general manager Fred Claire tells it in his memoirs, the Dodgers felt pressured to acquire a second baseman because their incumbent, Jody Reed, had set too aggressive a price in free agency. They bid on the Giants’ Robby Thompson, but all they succeeded in doing was pressuring San Francisco into signing Thompson to a more expensive contract. “If Jody accepts our offer, we keep Pedro Martinez.” Claire wrote. “If we sign Robby Thompson, we keep Pedro, and Will Clark probably stays with the Giants.” (Also a free agent, Clark left the Giants for the Rangers that winter.)

The Expos didn’t know they had made one of the greatest trades in baseball history. GM Dan Duquette crowed that dumping the arbitration-eligible DeShields for the salary-controlled Martinez was, “a powerful economic move.” Manager Felipe Alou was measured in his response. “This is a kid with a great arm…. Delino is on his way to being a superstar. If Martinez pitches well, this could be a good trade for both teams.” Said Montreal Gazette columnist Michael Farber, “This is the Expos’ one big deal to balance the books, one of those trades that gives Montreal baseball fans a sick feeling in their stomach.” As for the Dodgers, manager Tommy Lasorda said that DeShields, “will be more valuable to us than the relief pitcher,” echoing a similar statement by Claire.

The trade was made infinitely worse when DeShields stopped hitting. In 1996, he averaged .224/.288/.298 in 154 games, crashing to .184/.273/.222 in the second half. The Cardinals, desperate for a quality second baseman since the decline of Tommie Herr, signed him as a free agent and he made the Dodgers look bad one more time, hitting .293/.363/.440 over two years in St. Louis. Then an off year with the Orioles, then a good year, then the end. There must have been undisclosed injuries (in addition to several we know of, such as chicken pox early in 1993, a torn thumb ligament late that same year, and the broken thumb and quadriceps injuries that ruined his 1999) or off-the-field distractions, because few players have been so lacking in linearity

Society’s changed a lot. We grow up differently—faster, for one thing. Plus, you know, a lot of us black kids come from single-parent families and we’re raised by our mothers. It’s a fact, socially. A lot of us came from situations where we had to make key decisions and an early age.

I was like that. The way I see it, I made some major-league decisions well before I was in the major leagues.

—Delino DeShields, April 29, 1990

DeShields, nicknamed “Bop,” was noted for cuffing his pants high in the old-fashioned style. It was his homage to his Negro Leagues forebears. “That is just my way of saying, ‘Thank you for making all of this possible.’” He gave his son and major-league namesake, center fielder Delino DeShields, the middle name Diaab. “Diaab means ‘one who perseveres,’” he said in 1993. “Originally, I chose that name for myself. Africans lost a lot coming over here in slavery. I felt the name fit, and I said if I ever had a little boy I’d name him that. I came through a lot to get where I am. I want my baby to have those same characteristics.”

From Chapter Six: Team of Greats II.

PEE WEE REESE, SS

2166 G, 1940–42, ’46–58 .269/.366/.377 (99 OPS+), 68.4 WAR

Two of the best stories about Reese are mythical. It has long been said that the Red Sox purchased the Louisville Colonels solely to acquire Reese, who was property of the team in 1938 and ’39. That may or may not be true, but what isn’t is that the July 18, 1939, trade of Reese to the Brooklyn Dodgers was done at the instigation of Joe Cronin, Boston’s manager and starting shortstop, in order to protect his own position. The true explanation is even worse: He wasn’t trying to protect his position; he was only 32 in 1939, was still playing extremely well, and would continue to play well for another two years. He simply thought Reese wasn’t a prospect. That was it. He wasn’t venal, he just blew it. We might even exonerate Cronin completely: In some tellings of the tale, it was Tom Yawkey’s partners in purchasing the Colonels (Donie Bush and Frank McKinney) who prompted the sale so that they could realize the highest possible price on a top prospect rather than be shortchanged by a related-party transaction.

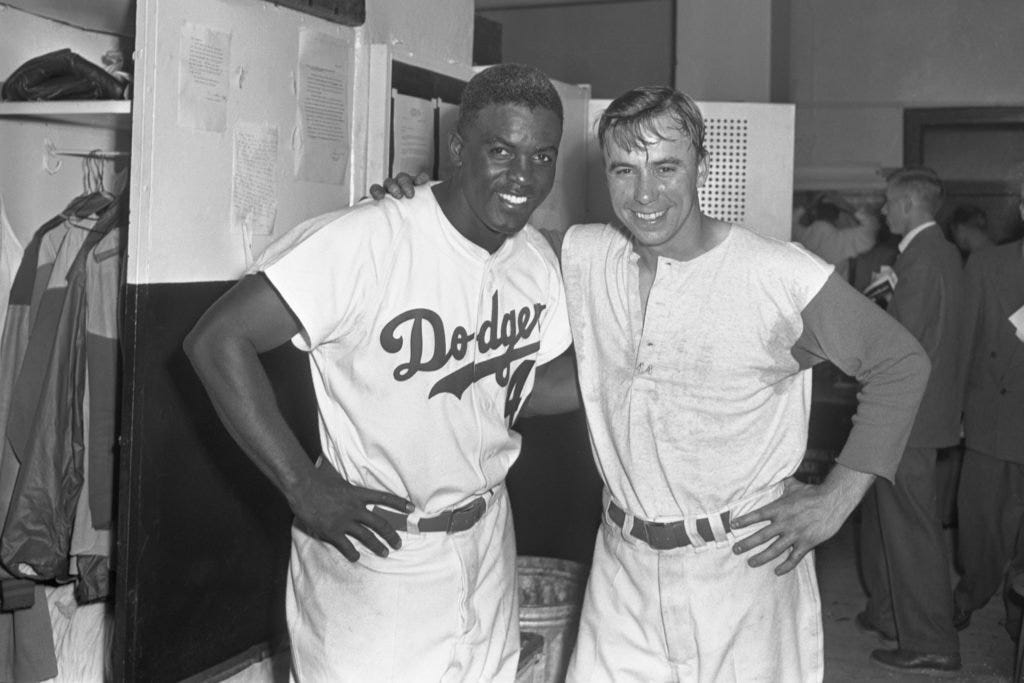

Sadly, the famous May 1947 embrace of Jackie Robinson by Reese in Cincinnati, supposedly in response to racist hecklers, probably didn’t happen, either, at least not then. Reese, a Kentuckian, was actually a little ambivalent about having a player of color on the team, but he got past it. That’s important. That matters. That Reese didn’t make a public spectacle of his support in 1947 diminishes the fairy-tale aspect of the story a bit, but that was always a lie, anyway. The result of the Robinson “experiment” was not the magical erasure of hundreds of years of received prejudices; Robinson helped move American conceptions of race by inches, not miles. It’s possible that Reese’s embrace—more metaphorical than physical—did take place the next year, in Boston (“letting the Boston players know that I was a friend of his,” said Robinson), and that’s plenty good enough, even if it’s not neat. “A really nice man is a rare man, and the crowd always spots him,” Robinson told John Lardner in 1949. “They sure guessed right about Pee Wee.” Given our legacy of white intransigence, we shouldn’t take “nice” for granted.

A familiar scene around Ebbets Field is an exchange between the fans in the boxes near the field and Reese, at his shortstop post. Often, some rabid Dodgers follower would yell in a raucous voice, “Hey, Peewee, have you had your milk today?”—and Reese always waves and nods his head, with a big smile on his face, to the delight of the crowd.

—Famous American Athletes of Today, 1947

Reese was an unusual player, and trying to find a recent analogue for him is difficult, especially given the three key seasons (ages 24–26) he missed due to World War II. Reese started out as a light-hitting gloveman but developed a little pop along the way. He also had excellent plate judgment, ran the bases well, and hit for good averages, though he only topped .286 once. That was in 1954, when he hit .309/.405/.455. If you could mix Willie Randolph and Alan Trammell you’d about have him, or Randolph and Chuck Knoblauch— which is to say, he had all of Randolph’s skills plus Knoblauch’s slightly greater power. (Hitter-friendly Ebbets Field didn’t have a notable effect on his power numbers—from 1940 through 1957, he had an isolated power of .107 at home and .107 on the road.)

Pee Wee Reese should go on to become one of the best shortstops in the history of the league.

—veteran catcher Spud Davis, 1941

When I finally decided to go and play ball in 1938, the man who got me the job at the telephone company said to me, “Pee Wee, I think you’re making a big mistake by quitting your job and going away to play baseball.” I said, “Mr. Lane, I’m young. I may as well give it shot.” And thank Heavens I did.

—Pee Wee Reese

He played shortstop for three generations of Brooklyn teams, and came to sport droll cockiness. Yet near the end, sitting on a friend’s front porch and watching a brown telephone truck scuttle by, he said with total seriousness, “I still can’t figure why the guy driving that thing isn’t me.”

—Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer

About the author:

Steven Goldman is the host of the Infinite Inning podcast, current consulting editor and former editor-in-chief of Baseball Prospectus, author of Forging Genius: The Making of Casey Stengel as well as editor and coauthor of numerous other books including multiple volumes of the bestselling Baseball Prospectus annual. He resides in New Jersey with his family, three cats, and an unmanageable number of books.

Media Savvy:

As long as we’re on the subject of interesting reads, below are three more for your consideration:

“Jackie Robinson’s final public appearance: 50 years ago at 1972 World Series,” by Rhiannon Walker at the Athletic.

“A nuanced perspective on Shohei Ohtani’s future with the Angels,” by Sam Blum at the Athletic.

“Baseball History Is No Longer Written With Ash Bats: Invasive insects and batter preferences have led to the elimination of the wood that dominated the sport for generations. There may not be a single ash bat used in this postseason,” by Zach Schonbrun at the New York Times.

Baseball Photos of the Day:

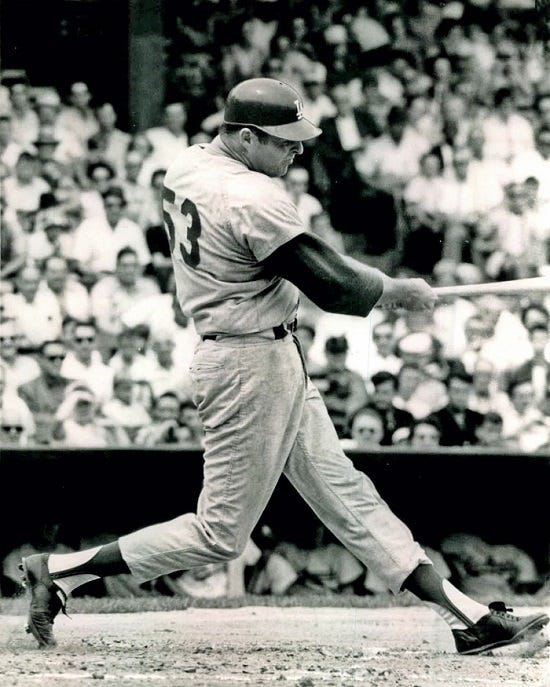

Don Drysdale.

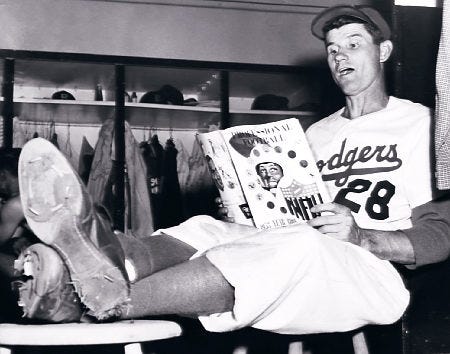

Preacher Roe.

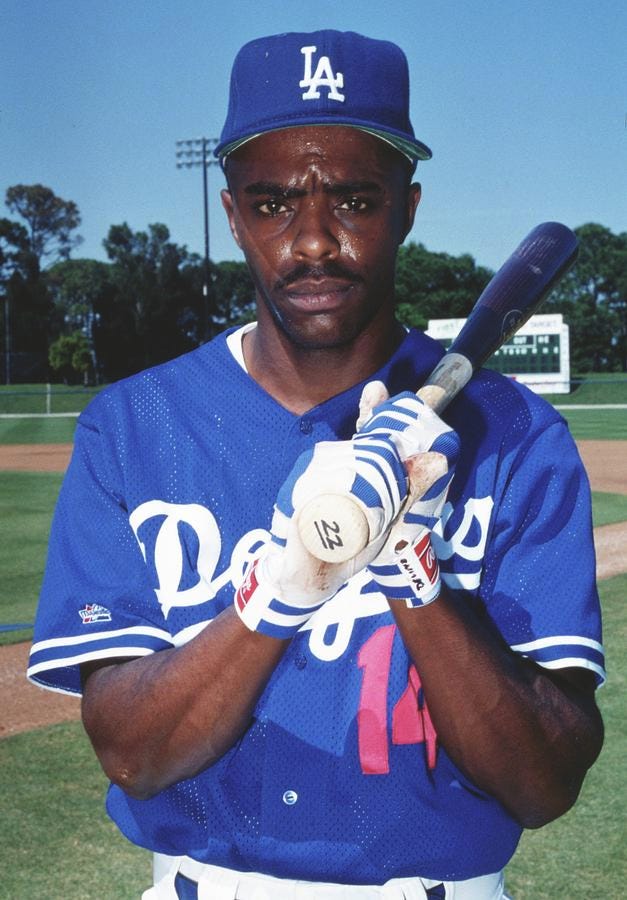

Delino DeShields.

Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.

“Yeah, but before he could answer he was on third.”