Book Excerpt: Classic Baseball: Timeless Tales, Immortal Moments, by John Rosengren

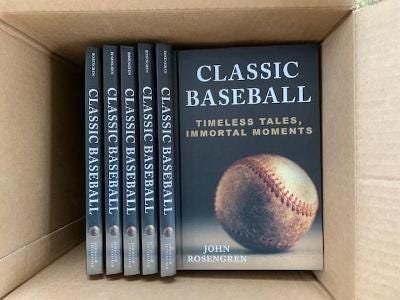

It happens every spring. New baseball books roll off the shelves just as Spring Training is (normally) in full swing. And I present book excerpts from new volumes from interesting authors. “Classic Baseball: Timeless Tales, Immortal Moments” by John Rosengren (Rowman & Littlefield, Kindle $30, Hardcover $32), out today, is one such work.

Rosengren is a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in The Atavist, The Atlantic, GQ, The New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, and the Washington Post Magazine, among more than 100 publications. He has published ten books, including Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes and The Fight of their Lives: How Juan Marichal and John Roseboro Turned Baseball’s Ugliest Brawl into a Story of Forgiveness and Redemption. His work has won numerous awards and been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He lives in Minneapolis and roots for the Twins.

I asked John to provide an elevator pitch, a kind of author-in-his-own-words description of his new book, and below is that pitch:

Baseball–rooted as it is in tradition and nostalgia–lends itself to the retelling of its timeless stories. So it is with the stories in Classic Baseball: Timeless Tales, Immortal Moments, originally by Sports Illustrated, The New Yorker, Sports on Earth, and VICE Sports, among others. Whether it be the story of John Roseboro forgiving Juan Marichal for clubbing him in the head with a bat or Elston Howard breaking down the Yankees' systemic racism to integrate America's team or a fan chasing the milestones of the game's best players or the national pastime played on snowshoes during July in a remote Wisconsin town, these are stories meant to be read and read again for their poignancy, their humor, and their celebration of baseball.

These are stories about the game's legends–Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Josh Gibson, Bob Feller, Frank Robinson, Sandy Koufax, Kirby Puckett, et al.–and its lesser-knowns with remarkable stories of their own. They cover some of the game's most famous moments, like Hank Aaron hitting No. 715, and some you've never heard of, like the time the Ku Klux Klan played a game against an all-Black team. All stories you'll want to pass along to your friends and young fans in turn.

I come at these stories as a SABR member with an MFA in creative writing, as a lifelong fan, as a former Little League coach, as a player (well into my fifties until I wrecked my throwing shoulder–what's a catcher who can't get the ball back to the pitcher?), and even an ex-umpire. I've watched the game from the press box and behind the plate; hit a single off Twins pitcher Rick Aguilera; talked to Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Yogi Berra, and plenty of others; spoken to audiences around the country about the antics of Charlie Finley and the heroism of Hank Greenberg; and impressed Leslie Epstein (director of Boston University's creative writing program and Theo's dad) with a short story about a guy who led the league in getting hit by pitches–when he berated my other stories. All of which has given me a broad and deep perspective on baseball, one that informs the stories set forth here.

Excerpt: The Legend of La Tortuga

Willians Astudillo is a utility infielder for the Minnesota Twins. And a cult hero. How did that happen?

City Pages, May 2019

Introduction: At the close of the 2018 season, a phenomenon began that carried over into 2019. Call it "Turtle Fever." Twins fans were smitten by an obsession for a flamboyant yet media-shy backup from Venezuela. I wanted to find out what beguiled them so and who this guy was.

This is not just any Friday night at Target Field. It’s “An Evening with La Tortuga.”

The Twins expected 2,000 fans to take them up on the offer of a ticket to the April 26 game against the Orioles and a Tortuga T-shirt. Demand was so high they had to print another 1,000 shirts–which promptly sold out.

In the stands above the home team dugout, a ten-year-old boy in a Twins cap watches the players filing off the field as batting practice winds down. Nelson Cruz passes by. Eddie Rosario. Byron Buxton. The boy doesn’t flinch. Finally he spots Willians Astudillo. He holds up a drawing of a green turtle and calls, “Tortuga!”

Astudillo stops. The boy tosses him a ball and pen. Astudillo signs the ball and several more for other boys who quickly gather before he heads into the clubhouse. The boys reverently regard his autograph.

Up on the concourse along the third-base side, a father walks with his eleven-year-old son, both wearing black La Tortuga shirts: a red No. 64 over a beige turtle shell on the back and the meme of Astudillo running on the front. Matt Guttman introduces his son Zach, “This is his biggest fan.”

Last summer, they attended the Twins’ final game–not to say goodbye to the old star, Joe Mauer, but to meet the new one. Matt pulls out his phone and flashes a photo. In it, La Tortuga leans into the stands, smiling with his new bestie, Zach.

Matt had the photo made into an 8” x 10” print, and when they heard Astudillo would be at Fan HQ in the Mall of America the previous weekend, they road-tripped there from their Plymouth (Minnesota) home. Matt shows another image on his phone of Astudillo signing the photo. They would not have missed this evening.

“He’s fun to watch,” says Zach, who plays baseball himself: third base, pitcher, outfield. “All over, kind of like him.”

Like many fans, Zach loves the guy. At the same time, he marvels at his quick rise to celebrity: “He doesn’t even have 200 at-bats in his [MLB] career, but is already having a theme night.”

Indeed, 142 at-bats, for those keeping score at home, and already he has not only a theme night, but a drink (La Tortuga Cocktail, served at Bat & Barrel and Town Ball Tavern) and a sandwich (La Tortuga Torta, served at a sandwich cart behind section 114) named after him. Astudillo T-shirts have sold more than any other Twins’. His highlights go viral more frequently than Rosario goes yard, which has made him an instant social media sensation and cult hero.

Astudillo has become the team’s most popular player faster than anybody in Twins history, yet he’s not even a regular starter. He’s a newbie to the majors, a journeyman minor leaguer, a twenty-seven-year-old utility fielder the marketing department esteems more than the manager, who hasn’t had the confidence to pencil him into the starting lineup this evening. Having a theme night for Willians Astudillo is like feting Jerry Terrell, retiring Al Newman’s number, or hosting a Nick Punto party. How did we get here?

Rocco Baldelli’s decision to have Astudillo start his evening on the bench enraged La Tortuga’s legions. The way they lit up social media with their frustration made it look like another Arab Spring. Their passion for him mirrors the passion he displays on the field. He’s captured their hearts. You see them post comments like “It’s not always easy to be positive about the Twins, but I love that guy,” from md56482. “The most compelling player the Twins have had in many years,” LoisMA. “Another reason why baseball is great,” Blake R., and “I love this man,” Margo L.

They call him the most talented Twin. A Hall of Famer. The GOAT. Obviously blinded by love, but forgive them. It’s been a long time since a player excited Twins Nation this much. We loved Kirby, of course. But he let us down with his dark side. Eddie Guardado had the spark but took nearly 10 years to catch fire. Torii Hunter was lovable but left. Going further back, Killebrew was too even keel. There’s simply never been a Twins player fans have fallen for so hard so fast.

The first thing you see when you look at Willians Astudillo is, well, his body. At 5-foot-9, 225 pounds, he looks more like a bowling pin than a professional baseball player. You might say, politely, he’s stocky. Husky. Chunky. Short for his weight. Could be the love child of Jack Black and Amy Schumer. A Prince Fielder Mini-Me. Bluto with a bat.

Which makes him all the more irresistible. The fan in the stands snarfing nachos from a plastic batting helmet or the guy on the couch at home with beer in hand looks at Astudillo and sees himself. “He doesn’t look like your typical ballplayer,” says Matt Guttman, who’s about Astudillo’s height yet slender. “He gives a lot of people hope you don’t have to be six-two and 250 pounds to succeed.”

Combine that with a rubbery face as flexible and expressive as Al Schacht’s framed by a mullet perm that’d be tops in any of John King’s hockey hair videos, and talent that pops up all over the field, and you’ve got the makings of baseball highlight porn. Here’s a quick tour:

The moment that got him noticed happened at spring training last year. From behind the plate, Astudillo catches the pitch and–without leaving his crouch or shifting his gaze from the pitcher–whips the ball to first base to pick off the runner, who doesn’t know what’s happened.

Playing third at Rochester in August, Astudillo fields a throw with a runner reaching the base and simply pockets the ball in his glove. When the pitcher climbs the mound, and the runner takes his lead, Astudillo pounces on him with the tag. Another runner out and left wondering, WTF?

Astudillo auditioned for the outfield with a clip he sent to Twins brass of him in center field during the 2014-15 Venezuelan Winter League season. He runs back to the wall, sets, jumps–well, more hops; he doesn’t really get much air–and nabs the ball before it disappears over the fence to deny a home run. He lands flat on his belly, rolls to his side, and raises his glove to show a clean catch–more seal performing a trick than Gold Glover.

In another fielding blooper converted into an out, this one while catching for the Twins last summer, Astudillo scampers from behind the plate to field a bunt, snaps a throw to third, collides with Jose Berrios coming off the mound, and falls flush on his face. That’s another reason he’s so entertaining–he can inject slapstick into the routine.

In a braver moment behind the plate this past April in Philadelphia, Astudillo stands his ground with the ball while Bryce Harper bears down on him. Harper tries to hurdle the turtle but collides with him. Astudillo falls back, rolls once, comes to rest on his knees, and raises the ball in his right hand to show the ump, I got him! The ump pumps his fist. Out!

Astudillo hit a walk-off homer for the Twins against Kansas City on September 9, but it was his performance after a game-winning blast earlier this year in the Venezuelan playoffs that deserves the Oscar. He swings so hard he finishes on one knee then holds the pose, forearms crossed over the knob of his upright bat, and watches the ball sail toward the left-field pole. “I thought it was going foul,” he said later. When he sees it stay fair, his enthusiasm carries him around the bases, past his teammates clumped at home, and through a routine of sideways jumping jacks the length of the dugout, exhorting cheers from the crowd. The clip’s a combination of sublime cool and unrestrained joy

But the instant classic, the one that solidified the Legend of La Tortuga, comes from September 12 at Target Field. Astudillo is on first when Max Kepler’s hit to left-center eludes Yankee center fielder Aaron Hicks’s dive. Astudillo rounds second and chugs for third. He sheds his helmet along the way–shades of Willie Mays in slow motion. He rounds third already gassed. With the throw from the outfield heading to the cutoff man, the drama plays out on Astudillo’s eloquent face. He’s grimacing, biting his tongue, willing the luggage of his body forward. His long curls unfurl behind him. He runs and runs and runs. He’s gasping. A drowning man fighting for air. The throw reaches the cutoff man. And still Astudillo chugs on. Finally–finally!–longer than it took Odysseus to find his way home, La Tortuga slides in safely.

After much ribbing from teammates and manager Paul Molitor admitting, “That was painful to watch,” Astudillo said, “I just wanted to show that chubby people also run.”

So that became his tagline. It’s on the front of the giveaway T-shirt, above the image of him on his mad dash over the words RUN, RUN, RUN.

The personality that fueled his 270-foot run and his reply are infectious among fans and his teammates. Astudillo grew up choosing Nelson Cruz for home run contests playing MLB video games, yet he’s brash enough to call the veteran “Vieja” (Old Lady) in jest. Cruz retorts with “Señor Barriga” (Mr. Big Belly). “He gets mad at me,” Cruz says, laughing. Before the game on La Tortuga night, Cruz wears one of the black promo shirts along with a handful of teammates. “He’s just fun to be around," he says. "Always positive. He brings good energy to the clubhouse.”

Kyle Gibson agrees. He likes pitching to Astudillo–whom he calls “Torts”–and playing cards with him. “I’m on a pretty good streak of beating him in the card game Casino right now. I give him a hard time about that,” Gibson says. “Because he’s a young guy, he ends up being the brunt of some jokes. He also kind of brings it on himself and enjoys it a little bit. He likes to make jokes and take jokes at the same time. He’s one of the guys who keeps it light around here.”

He seems to inspire that sort of reaction in everyone. When asked to comment on Astudillo, Twins catching coach Bill Evers smiles reflexively. Why? “Because he brings that energy every day to the game,” Evers says. “He’s fun to watch because he plays with passion. He cares about what he does, and he puts the time and effort into it.”

“I don’t know how you can talk about him and not smile,” Baldelli said in a taped television interview. He’s smiling himself, his eyes gleaming. “He’s a really enjoyable player to watch for a lot of reasons, but he’s also a really talented guy. This is a guy who has a really unique ability with a bat in his hands.”

He’s talking about Astudillo’s ability to make contact. The Turtle is a free swinger who seems to be able to hit the ball wherever it’s thrown. Back in spring training, the BP pitcher was messing with him. He edged his pitches farther and farther outside. Astudillo kept getting his bat on them. Then he moved inside, closer and closer. Same thing–Astudillo swung and made contact. Finally, the pitcher tossed a ball behind Astudillo–who turned and whacked it with an axe stroke.

Astudillo figures he developed his hand-eye coordination as a boy when his father, a retired professional baseball player, flicked corn kernels in the back yard that Astudillo picked out of the air with the swing of a broomstick. Try that at home.

Through the end of April, he had the best contact rate in the majors. His 96.8 percent was way higher than the MLB average of 76.9 percent last year (meaning when batters swung, they made contact roughly three out of four times). That skill makes him an ideal pinch hitter or batter in hit-and-run situations.

His extraordinary hand-eye coordination means he almost never strikes out, an anomaly in this age of the inflated strikeout rate. In the minor leagues, he had the lowest strikeout rate among all double-A and triple-A players the past two years and among all minor league players the two years before that. In 2,461 plate appearance throughout nine seasons, he struck out only 81 times, a measly 3.3 percent. (Anything under 10 percent is considered excellent.) In the Show, he has become the batter least likely to strike out in major league history, relative to the league. With five career home runs and four walks, he is the only MLB player with at least 150 plate appearances in the past century to have more home runs than strikeouts.

Astudillo likes to swing at the ball. He doesn't like to walk. Throughout his nine seasons in the minors, he walked as infrequently as he struck out, only 85 times or 3.5 percent of his plate appearances. He had not gotten to a 2-0 count in the majors until April 6 of this year.

When the next pitch is a ball, Twins television play-by-play man Dick Bremer observes, “Now three-and-oh to a man who’s hard to walk."

“Probably a career high with three straight pitches taken,” commentator Justin Morneau adds, chuckling.

The next pitch is a high fastball, slightly outside. He could take it–the way most batters would–for ball four and a free pass. But Astudillo, who has already bashed one home run that afternoon, swings big. Misses. And falls down.

Bremer laughs.

Astudillo fouls off the next pitch. Full count.

The Phillies pitcher delivers a 92 MPH fastball inside at the knees. Astudillo backs away.

“Astudillo has drawn a walk,” Bremer declares. “And what will be in the headlines in the newspaper tomorrow? A possible Twins win? Their three home runs? Or the fact that Astudillo has drawn a walk?!”

“All we need is a stolen base to top it off,” Morneau cracks. (That would be another major league first for La Tortuga, who comes by his nickname honestly.)

As SABRites worship at the altar of the “three true outcomes” (home runs, walks, and strikeouts), Astudillo is guilty of apostasy. Through the first month of the 2019 season, he had one walk and one strikeout. Plus two home runs. Here’s yet another aspect of his appeal. Not only is he a maverick as a disciplined free swinger, he’s also a free thinker in the batter’s box.

Despite his life-of-the-party reputation, Astudillo is subdued and serious during a pregame interview in the dugout. He answers questions in Spanish that are translated by Elvis Martinez, the Twins’ interpreter, to a reporter. Afterwards, Martinez points out Astudillo’s business-like manner is his standard M.O. with media. Astudillo came from nothing in the port town of Barcelona, Venezuela, and while he’s working near the major league minimum wage of $550,000 a year, he knows that if he doesn’t make it, poverty awaits him.

The Turtle went at his own pace through the minors. Signed by the Phillies shortly after his 17th birthday, he spent three years in the Venezuelan Summer League before winding his way through the Gulf Coast League, the South Atlantic League, and the Florida State League, only to be released by the Phillies in 2015. Signed by the Braves, he played a summer in the double-A Southern League and was released.

Winter ball in Venezuela seemed the only constant. Signed by the Diamondbacks, he batted .342 in the triple-A Pacific Coast League, but instead of being promoted, he got released. Again. The Twins signed him in November 2017 and sent him to Rochester in the triple-A International League. The man paid his dues, another credit in his favor among Twins fans with their Midwestern work ethic.

When the Rochester manager told Astudillo in late June 2018 that the parent club had called and wanted him to join the team in Chicago, he was so excited, he telephoned his parents in Venezuela, even though it was late at night. He woke them up. They didn’t believe him. Ten long years had passed since the major leagues had first expressed interest. They thought he was joking.

But it was true. In a game against the Cubs on June 30, Molitor sent Astudillo out to left field in the fifth inning to relieve Rosario on a very hot day. “I was extremely nervous, especially playing in Wrigley and in the outfield, not my natural position,” he tells Kyle Gibson on his podcast “Meeting on the Mound.” “But it felt really good to be out there and in the big leagues and to show people what I can do.” That included a single in his major league debut at-bat, which drove in the tying run. He also caught two flyballs, made no errors. And so the legend began.

Even though he lasted only three weeks, Astudillo burnished the legend when he took the mound to finish out a game already lost to the Tampa Bay Rays. Astudillo, who had won a game the summer before pitching two scoreless innings for triple-A Reno, did not threaten the job security of anyone in the Twins bullpen. He gave up five runs, including a homer to the first batter he faced. But he appeared so overmatched–David pitching to Goliath yet persevering–that he won over the fans, who embraced him as the lovable underdog.

Astudillo is listed as a catcher, though it appears he can play anywhere (except maybe pitcher). Called up again in September, he played first, second, third, left field, center field, and catcher. This season, he has added right field to his résumé. That’s led to speculation of him playing all nine positions in a game like fellow Venezuelan and Twin Cesar Tovar did in 1968. Molitor introduced the idea as a joke last year. Baldelli has toyed over it with reporters but recently insisted he would not be putting Astudillo at shortstop, the last position for him to check off the list.

Astudillo himself says he has no aspirations of following in Tovar’s footsteps–though he insists he could, pointing to 10 years playing shortstop as a youth. He thought he was going to get his chance in spring training this year when he saw his name at short on the lineup card for the next day’s game. He texted friend and countryman Ehire Adrianza, nervously asking for some helpful advice. But the assignment turned out to be a clerical error, and the next day Astudillo was at second, not short.

Still, he has proven his value with his versatility. This year and last he has appeared most often at the infield corners when he’s not behind the plate–or on the bench. Through the Twins’ first two dozen games, Astudillo had started only four games at catcher and 14 total, little more than half. Management does not seem to have complete confidence in him as a catcher, preferring the experience of Jason Castro, who had started 11 games behind the plate in the same span, or the promise of Mitch Garver, who started nine. Last year, in his first call-up, Molitor didn’t use Astudillo at catcher once.

Catching coach Bill Evers notes that Astudillo has made progress as a catcher, is adapting to implementing the game plan, and is becoming more adept with his soft hands at framing pitches to win strikes. When asked, Do you think catcher is his best position? Evers replies, tellingly, “I think he is a wonderful utility man that brings energy all over the diamond and has the athleticism even though the body type does not [make you] think of a great athlete. His an excellent athlete that can play other positions.”

So don’t expect Evers to be lobbying for Astudillo to assume the starting job behind the plate. General manager Derek Falvey has admitted, too, that he and his scouts haven’t been quite sure how to best employ Astudillo’s talents, which included a .320/.340/.531 line with 2 HR and 7 RBIs before a 10-day sabbatical on the injured list from late April into early May. La Tortuga defies standard models and current projection metrics. “There are not many [comparisons] for him,” Falvey said during spring training.

That may explain why Astudillo’s role on his special night has been limited to three brief cameos warming up the pitcher while starting catcher Mitch Garver straps on his gear. It’s not until the bottom of the eighth inning, with the game seemingly in hand, that Baldelli gives the fans what they’ve paid to see.

When Astudillo is announced over the p.a. system to lead off, the fans applaud happily, sounding louder than the 15,000 or so there.

Inspired, La Tortuga goes all in on the first pitch. He clips a foul with a swing so mighty that the follow-through staggers him across the plate to the other side.

Astudillo steps back, taps his spikes with his bat, and settles into the batter’s box. He lines the next pitch sharply but foul of the left-field pole. Fittingly, a man in one of the black Tortuga T-shirts comes up with the ball and holds it high for everyone to see.

Down 0-2 in the count, Astudillo checks his swing on the next pitch, which is outside. The catcher appeals to the first base ump.

In the press box, a reporter says, “You can’t call him out on La Tortuga Night.”

He doesn’t. The ump signals no swing. The fans exhale.

The next pitch is a breaking ball tailing off the far side of the plate. Astudillo swings–and connects, rapping a sharp grounder up the middle past the Orioles’ diving shortstop. The Tortugans let out a roar and rise to their feet.

On the railing of the Twins’ dugout, Cruz and Rosario burst into a big laugh. They clap above their heads for Señor Barriga to see.

Morneau marvels that Astudillo was able to get the barrel of his bat on a ball so far off the plate. “That’s what makes him special,” he tells the home audience.

Giggles spread through the press box. It’s as though the game’s followed an improbable yet predictable script. Astudillo has played his part, stoking the legend.

The crowd chants, “La Tortuga! La Tortuga!”

Everyone’s caught up in the moment. Morneau remarks, “That’s pretty cool to see. For a guy who’s grinded his way through the minor leagues, to get an opportunity and see everyone embrace him like that. It has to put a smile on your face.”

Tomorrow afternoon, La Tortuga will start in right field. He’ll lead off the seventh inning with a single and later make his way to third on a throwing error. He will tag up on Kepler’s sacrifice fly to left and break for home. His face will strain with the effort but then, five strides from the plate, it will flash with pain, and when you look at the replay, you’ll notice him pulling up on his left leg. His run will break a scoreless tie and put the Twins up 1-0 in a game they will eventually win 9-2. But Astudillo’s expression will be serious as he makes his way through the congratulations in the dugout. He will spend the balance of the game on the bench, and the next day the Twins will place him on the 10-day injured list with a “left hamstring strain.”

But for that moment, standing on first base Friday night, the ovation consummates “An Evening with La Tortuga.” Astudillo feels the love cascading down from the stands and emitting from his teammates. Words can’t quite capture this feeling, but he tries in an Instagram post the next morning along with a clip of his pinch hit: “Seriously, you all have no idea how much it means to me, someone who had to fight to get here, to hear this. Thank you. Sincerely, thank you.”

Postscript: After coming back from his hamstring strain, Astudillo injured his oblique making a leaping catch in late June and missed much of the rest of the season, appearing in only 58 games with the Twins. He still managed to play every position except shortstop and pitcher and finished with more doubles (9) than strikeouts (8). At the start of 2020 season, Astudillo was quarantined after testing positive for COVID-19 and saw limited action once cleared to play, appearing in only eight games during the shortened season, going 4-for-16 with no walks.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.