Book Excerpt: Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers

Chapter 19: Speaking ‘Catcherese’

Oh, what a fun book. And a wonderful trip down memory lane. With number 23 in our book excerpt series, I am happy to recommend “Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers,” by Erik Sherman (University of Nebraska Press, May 1, 2023, $15.99 Kindle, $32.95 Hardcover). It is the story of Fernando Valenzuela and the 1981 Dodgers season, from start to glorious finish.

The work is chock full of beautifully written stories about Fernando, and while I almost chose a chapter called “Houston Has a Problem,” about the first ever post-strike National League Division Series, I went with a chapter about the 1981 World Series instead. Because nothing could be more important than beating the Yankees in the Fall Classic, especially after dropping the first two games in New York.

Chapter 19: Speaking ‘Catcherese’ begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

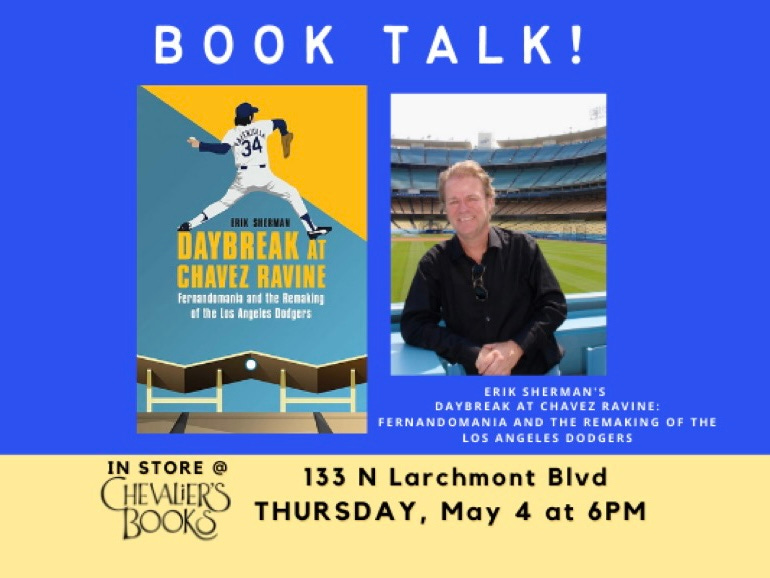

Meet Mr. Sherman, get a signed copy, Thursday at 6:00 p.m.

Chapter 19: Speaking ‘Catcherese’

The Dodgers’ desperation was as thick as the smog that hovered over downtown Los Angeles. The Yankees had won the first two games of the World Series in New York by playing every facet of the game flawlessly. From the magnificent starting pitching of Ron Guidry and Tommy John, the jaw-dropping defensive clinic put on at third base by Graig Nettles, the clutch hitting of Bob Watson and Lou Piniella, to the dominance of their closer Goose Gossage, the Yankees appeared every bit the team on a mission to capture its first World Series title in three years.

Now back at Chavez Ravine for Game Three, the Dodgers once again turned to Valenzuela to save their season. And for a team that appeared to be on the cusp of a major transitional phase, there was an awful lot riding on this must-win contest for LA. “There was a sense with the ‘core’ that this might be their last shot together,” Lyle Spencer said. “And, as it turned out, it was. They had been through those gut-wrenching World Series in ’77 and ’78 where they thought they were better than the Yankees and lost, so they had a lot of back history for that reason. A failure under pressure. So that’s why it was so meaningful to them. Most of the guys had been there in ’77 and ’78 and understood the pain. They didn’t want that again. They also were coming through in the clutch now, with Monday’s classic home run being an example of that. It was a combination of things that gave them hope. It wasn’t just Fernando, but in a sense, it was, because he was the catalyst.”

Pedro Guerrero, a member of the Dodgers’ “Kiddie Corps” and thus a player who hadn’t been around during the previous World Series matchups between these two longtime October rivals, was brimming with confidence. “When I was in the Minor Leagues in Arizona in 1978, I remember watching the Dodgers lose the World Series to the Yankees for the second straight year and said, ‘Hey they’re not going to win the World Series until I get there!’”

Still, it appeared these Yankees were peaking at just the right time— crushing teams like a runaway freight train. Like the Dodgers, they had clinched a spot in the divisional series by finishing the first half of the season atop the American League East. But with little to play for in the second half, they performed listlessly—posting a losing record of 25–26. Then, after taking the first two games of the divisional round against the Milwaukee Brewers, they dropped the next two at Yankee Stadium to force a decisive game five. Even in that game, they trailed 2–0. But then, as if on cue, they caught fire. Reggie Jackson, the man they called “Mr. October,” crushed an upper-deck two-run homer to tie the game. Then, the very next batter, Oscar Gamble, gave the Yankees the lead by stroking a home run into the right-field bleachers. From there, the Bronx Bombers piled on and won going away, 7–3, to advance to the American League Championship Series. From there, they pummeled their once and future manager Billy Martin and his upstart Oakland A’s in as dominating a three-game sweep as there ever had been in a postseason, outscoring them by a 20–4 margin in the series. And now, they were up two games to none over the Dodgers in the World Series—even without the services of an injured “Mr. October.”

If not for the promise of Valenzuela being on the hill at Dodger Stadium for Game Three, as well as the Dodgers’ uncanny ability thus far into the postseason to come back after being down in both the Houston and Montreal series, the prospects of an LA championship for the first time since the days of Koufax and Drysdale, dating all the way back to 1965, seemed bleak at best. But because of the way things were playing out for the Dodgers that October, they still had hope. “After dropping the two games in New York,” Steve Garvey recalled, “we’re on the plane flying back to LA and the guys are standing in the aisle talking. I say, ‘Well, we’ve got them right where we want them. We’ve had leads in the past. We’ve blown those. We were up 2–0 in the ’78 World Series and that didn’t work. So, why not? Do you see a pattern here—even destiny?’ And everyone was like, Yeah, maybe there is.”

“We didn’t read too many papers or turn on the television while we were down 0–2 to the Astros,” Monday added. “And we didn’t listen to too many of the experts when we had to win two in a row against Montreal. And we didn’t read the papers after we lost the first two to the Yankees. We were just either stupid enough to believe that we could do it or cocky enough to believe that we could do it.”

Valenzuela would be matched up against the Yankees’ own rookie left-handed sensation—Dave Righetti—who compiled a record of 8–4 with a 2.05 era during the regular season and a 3–0 mark in the postseason. The two young stud pitchers could have been teammates in New York had the Yankees outbid the Dodgers for Valenzuela’s services with their offer to Yucatán, of the Mexican League, two years earlier. The Yucatán team’s owner, Jaime Perez Avilla, told the New York Times in 1981, “When the Yankee scout [Wilfredo Calvino] talked to me about [Valenzuela], he didn’t make a good offer. He told me, ‘The boy is good, but I’ll be doing you a favor by signing him.’ Naturally, he was bluffing to see if he could get him cheaply.” The difference in the Dodgers’ purchase price of $120,000 and the Yankees’ reported offer of $50,000 was significant back then for an eighteen-year-old pitcher, though the idea of how just a $70,000 margin would alter the history of the Dodgers, their Mexican American fan base, and the club’s fortunes is mind-boggling.

Alternatively, the hurlers could have also been teammates in Dodgers uniforms. As noted in the book They Bled Blue, the Dodgers almost traded for Righetti in 1980, offering Don Sutton in exchange—but the Yankees got cold feet and offered the less-talented pitcher Mike Griffin instead. The Dodgers turned that deal down cold. The premise that the World Series would likely come down to the left arms of two rookie pitchers wasn’t lost on Righetti. “[Valenzuela] has to get our hitters out; I have to get the Dodgers out,” Righetti told reporters before the game. “But it’s great. It adds excitement to the Series. But I think there’s more pressure on him than me. It’s a shame that they’re in their biggest game they’ve had all year and that he’s a rookie and it’s all in his hands. But they say he’s their savior.”

The Dodgers’ savior, who had been magnificent in the postseason to that point with a 1.71 era in four starts, would catch a break with Jackson still ailing and now Nettles also out of the Yankee lineup after badly spraining the thumb on his glove hand while diving for a Bill Russell hot smash single in Game Two. But neither Valenzuela nor his counterpart in Righetti would be sharp at the outset of what was deemed to be a glorious pitcher’s duel between the two aces. Fernando escaped trouble in the top of the first when he induced Piniella to hit into an inning-ending double play ball after walking lead-off hitter Willie Randolph and then Dave Winfield, and Righetti yielded a three-run homer to Cey in the bottom half of the inning. But the Yankees then battled right back in the top of the second when Watson continued his torrid hitting with a solo home run, which was followed by a Rick Cerone double and then, one out later, an rbi single by Larry Milbourne to cut the Dodgers’ lead to 3–2. An inning later, Cerone blasted a two-run homer to give the Yankees a 4–3 lead.

This was clearly not what anybody expected—especially out of Valenzuela pitching at Dodger Stadium. “The extra round of postseason games and pitching on three days’ rest may have started taking its toll on Fernando,” Jerry Reuss theorized. “But it was the postseason, and in a lot of cases the adrenaline takes over. So you’re allowed a rough ball game occasionally. Everybody understands that, because this is the Major Leagues—it’s supposed to be that way. It’s not easy all the time. So if you have a rough game and you still can battle your way through it, like Fernando was doing in the third game, it’s impressive. I imagine every time Van Gogh picked up a paintbrush, he didn’t create a masterpiece, that there were some that he looked at and probably said, ‘No good, I’ve got to start again.’”

Valenzuela, unlike Van Gogh, couldn’t start his work over again, though, as Reuss suggested, he could still grind it out. But Lasorda was nervous. Going down 3–0 in the World Series was not an option, and he quickly got Dave Goltz up in the bullpen. Lasorda was known for his quick hook in pivotal World Series games. In what has become more Lasorda YouTube gold, the Dodgers manager was mic’d up when he removed starting pitcher Doug Rau in just the second inning of Game Four of the 1977 World Series. Rau and Lasorda famously jawed at one another on the mound and all the way back into the dugout. But Fernando’s pitching, especially in 1981, was far superior to Rau’s, and Lasorda clearly was going to give him more rope than he usually would a struggling starter.

“I think Lasorda’s mind-set was, I’m going to leave him out there. I’m going to win or lose with him,” Garvey said. “It was kind of a safe pick, because guys went nine innings back then and threw 150 pitches. So it was smart leaving him out there to pitch through it. It was very comparable to having him work out of [trouble] like he did in the first inning of the last game in Montreal. Because if we lose this game, we’re down 0–3. And even if we win the next two, then we’ve got to win two more in New York and the odds get exponentially greater against us.”

Luckily for the Dodgers, Righetti continued to struggle as well, surrendering a Garvey single and a walk to Cey to start the bottom of the third inning. Yankees manager Bob Lemon had seen enough and removed the left-hander from the game. The move, at least initially, worked well, as LA couldn’t cash in that inning, because Yankees reliever George Frazier shut them down to maintain New York’s 4–3 edge. But the inning did generate an interesting development that would pay immediate dividends for Valenzuela. When Lemon removed the left-handed Righetti in favor of the right-handed Frazier, Lasorda went to his bench and had the left-handed Mike Scioscia pinch-hit for and replace Steve Yeager as catcher in the game. By all accounts, Valenzuela was more familiar with and comfortable pitching to Scioscia. Because of Lasorda’s platoon system with his two catchers, with playing time contingent on whether the opposing pitcher was a left-hander or right-hander, Fernando pitched most of his games with Scioscia behind the plate. Additionally, because the two were close in age, Scioscia spoke at least some broken Spanish, they were both more in sync with pitch selections, and Scioscia was less demonstrative than Yeager, they were a perfect fit.

The move paid immediate dividends. Fernando settled down and retired the Yankees with scoreless fourth and fifth innings. “[Scioscia] would say, ‘Let’s throw this pitch,’” Valenzuela told mlb.com in 2021. “I would just go, ‘No, no, no,’ and he already knew what I wanted to throw. There was very good communication, very timely. In a game, that understanding is very important between the catcher and the pitcher.”

However, through five innings, Valenzuela’s pitch count had already surpassed the century mark and there was activity once again in the Dodgers’ bullpen, with both Goltz and Tom Niedenfuer up and throwing. “I was warming up in the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth innings,” Niedenfuer said. “So, I was ready.” But Lasorda continued to stick with Valenzuela, even when it would have been completely understandable to have someone pinch-hit for him in the bottom of the fifth after the Dodgers took a 5–4 lead with an rbi double from Guerrero and a run-scoring double play hit into by Scioscia. The obvious question then became, If Lasorda didn’t get a pinch hitter for Fernando at a hundred-plus pitches in the fifth and with Guerrero standing on third with a valuable insurance run, when would he? “I always had confidence every time Fernando pitched that he would go nine innings no matter what,” Guerrero said. “That was always a good thing because it gave us confidence. It didn’t matter what kind of trouble he got into because he could always get out of it and then, boom, boom, boom, he starts striking out hitters. He was something else. That’s why we called him ‘El Toro!’”

As Fernando returned to the mound to pitch the sixth, he looked invigorated—nothing like a pitcher looking to come out of a game. “He was such a fierce competitor to stay in that game,” Spencer said. “And people weren’t aware of pitch counts back then. There’s no way he would have stayed in that game now.”

Still, after Fernando walked lead-off batter Randolph, Lasorda came out for a mound visit. As legend has it and as reported in numerous pieces on the encounter, the Dodgers manager told Fernando in his native language, ‘If you don’t give up another run, we’re going to win this ball game.’ To which Valenzuela, realizing they led by a run, answered back drily in English, ‘Are you sure?’ As Lasorda would explain later, it was his way of giving the pitcher something to strive for, knowing that his pitcher wanted to keep battling and try to finish what he started. “There were several [mound conversations] that I don’t remember,” Valenzuela told mlb.com. “But to stay in the game and to not be taken out, I was always trying to evade him and give him the runaround or go someplace else to avoid having him approach me and have that conversation.”

Lasorda’s trip to the mound proved effective, as Scioscia would proceed to throw out Randolph on his attempt to steal second base and Valenzuela would then finish off the inning with a strikeout of Jerry Mumphrey and a groundout of a now seriously slumping Winfield. “Fernando pitched well beyond his years, from Day 1,” Scioscia told mlb.com in 2021. “When he came up in 1980, you saw there was a composure that he had, a poise that sometimes players have to work into. He had it right away, and I think it was exemplified in Game 3 against the Yankees. The confidence that we had in him, along with what Tommy and the coaching staff had in him was very real and we just knew that, somehow, he was going to get it done.”

Scioscia’s own solo trips to the mound as Valenzuela weaved in and out of trouble seemed to have a soothing effect on Fernando, as well. “They talked, so they must have understood each other,” Reuss said. “Maybe they speak a third language—‘Catcherese!’”

Valenzuela would pitch effectively and economically over the next two innings but with some major help in the eighth from an outstanding play at third by Cey. After Aurelio Rodríguez (filling in at third base for Nettles) and Milbourne started off the Yankees’ eighth with back-to-back singles to put runners on first and second, Bobby Murcer was sent up to bat for relief pitcher Rudy May. Murcer popped up a sacrifice bunt attempt slightly into foul territory along the third base line. Cey charged in and dove head-first to snag it, then sprang to his feet and fired to first base to double up Milbourne for a double play. It was easily the defensive gem of the game. Valenzuela then retired Randolph on a fielder’s choice grounder to third base to end the inning.

The score remained at 5–4 heading into the top of the ninth with Valenzuela—considering his pitch count and his unflattering line of nine hits and seven walks—somewhat miraculously still in the game. But Fernando would finish strong—a groundout by Mumphrey, a flyout by Winfield, and a swinging strikeout of Piniella to close out a 147-pitch performance for the ages to get the Dodgers back in the series. “[Lasorda] knew what I could do, and I think that’s one of the reasons why he let me finish that game,” Valenzuela said.

“I’ve talked with Fernando about which game in his career was his favorite,” Spencer said. “He said it was Game Three of the ’81 World Series, when he had sixteen base runners out there and still won the game. It was a game in which he had to pitch through trouble all night in his World Series debut that set the Dodgers up to win the world championship. For the team, I think it was liberating. You can’t overstate the importance of that game, just like you can’t in the final game he pitched in Montreal. He just put the Dodgers on his shoulders. And I think that’s why he was just so beloved the rest of his career. Because if you’re an athlete, you understand how remarkable those kinds of performances are. Basically, he saved the Dodgers’ season repeatedly. They could not have gotten to the World Series or won the World Series without him. And every player on the team knew that and appreciated that for the rest of their lives. What he did in Game Three just capped off the most amazing season by a baseball player I’ve ever witnessed. What could he possibly do? The only thing comparable would have been one of Koufax’s seasons—in ’63 or ’65—in terms of putting a team on your back and willing them to championships.”

For Fernando, the final pitch of Game Three—a screwball, of course— would end up being the last of his magically historic 1981 season. But his last pitch capped off far more than a World Series game. It sealed his legacy as the perfect hero with the imperfect body that inspired millions of Latinos to aspire not just to become baseball players but to pursue whatever their dreams might be. If he could do it, then why not them? Valenzuela had also single-handedly made it cool—or at least acceptable—for Chicanos to become Dodgers fans, or at least baseball fans, for the very first time. Fernando Valenzuela had sealed his legacy as a legendary figure on the baseball field and a transcendent one off it.

About the author:

Erik Sherman is a baseball historian and the New York Times best-selling author of Kings of Queens: Life beyond Baseball with the ’86 Mets and of Two Sides of Glory: The 1986 Boston Red Sox in Their Own Words. He is the coauthor of five other highly acclaimed baseball-themed books. Sherman will be a 2023 inductee to the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame for his baseball writing and hosts the 'Erik Sherman Show' podcast. Visit ErikShermanBaseball.com.

I was at that game, and it was one of my top-three in-person games; the other two were pennant-clinching games in ‘74 and ‘88. Both of those had unusual backstories for me, personally.