Book Excerpt: Dodgers!: An Informal History from Flatbush to Chavez Ravine

Chapter 7: Sandy And Big D Will See You Out.

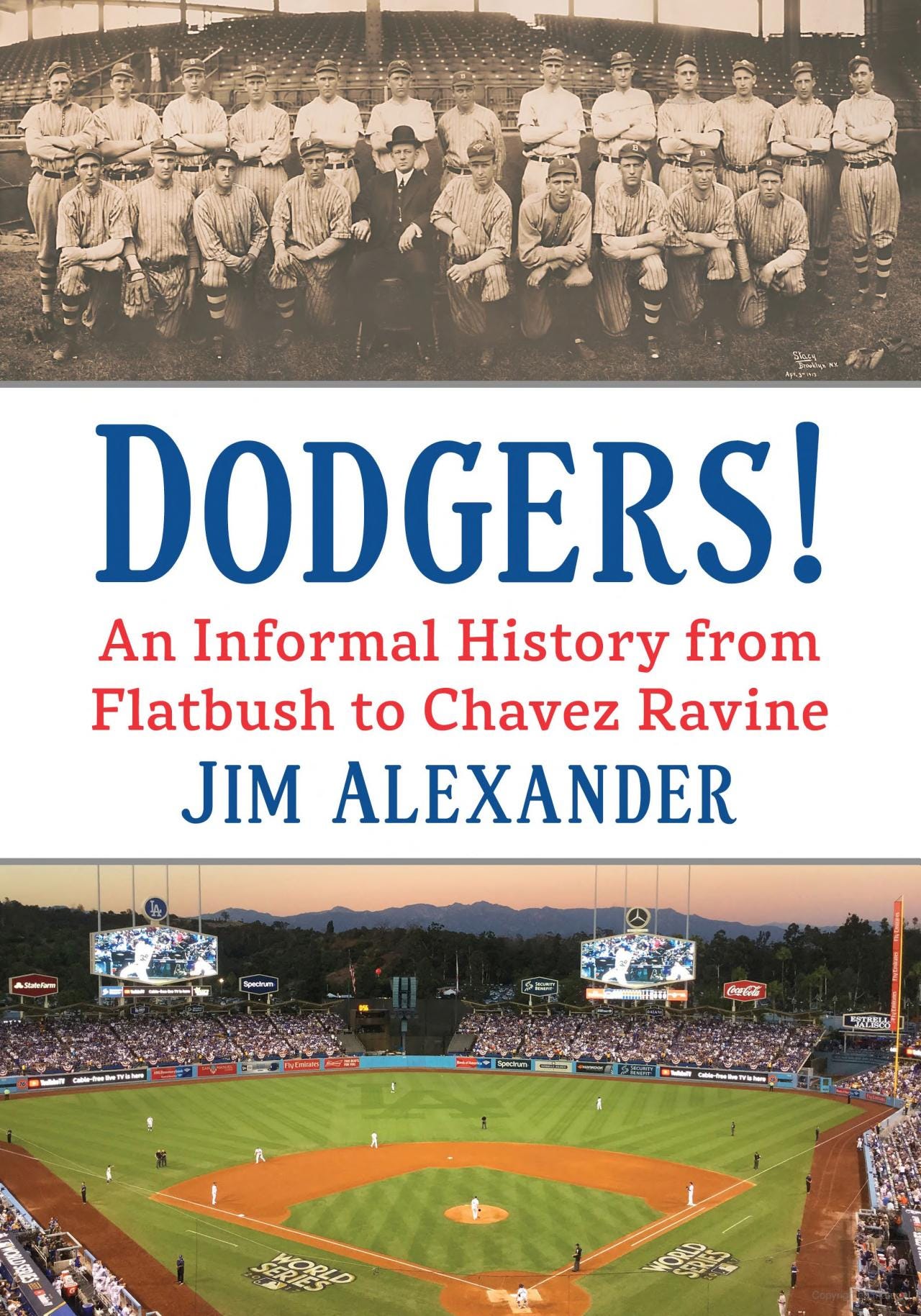

With number 12 in our book excerpt series I am please to recommend “Dodgers!: An Informal History from Flatbush to Chavez Ravine,” by Jim Alexander (McFarland, 2022, Kindle, $22.49, Paperback $49.95).

The excerpt I have chosen to share is Chapter 7, titled “Sandy And Big D Will See You Out,” which begins below.

I asked Mr. Alexander to introduce the chapter to interested readers, and here is that introduction:

“This was a project more than two years in the making, putting together the full history (if informal, as the title suggests) of the ballclub that had its roots in 1880s Brooklyn, now plays in the L.A. ballpark Tom Lasorda used to refer to as “Blue Heaven on Earth” and has a nationwide following. And it has ample references to Vin Scully, simply the best broadcaster of all time — and as I noted in a column following his passing this week, you can argue the point but you’ll never win that argument in this community. Amazingly, Vin’s 67 years of Dodger play-by-play through 2016 made up nearly half the lifespan of the franchise, which will play its 140th professional season in 2023.

“(Vin has a starring role in this excerpt, which recounts arguably the greatest game ever pitched, on both sides, and a ninth inning broadcast by Scully that was perfect in its own way.)”

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 7: Sandy And Big D Will See You Out

When Dodger Stadium opened in ‘62, built specifically for baseball and with fairer dimensions than the Coliseum, it nevertheless was a pitcher’s park first and foremost, which helps explain all those Cy Young Awards won by men who pitched there regularly.

The power alleys were originally 385 feet and straightaway center field 410 feet away. The crushed brick infield was extremely firm and fast; I remember a Baseball Digest story about the 1965 World Series between the Dodgers and Twins in which Minnesota third base coach Billy Martin was quoted as saying, “We have no infield in our league as hard as this,” momentarily forgetting that his team played the Angels nine times in that very ballpark. And the mound was, shall we say, tailored to the needs of the home team’s pitchers. Its height as dictated by the rule book was then 15 inches. At Dodger Stadium? Let’s just say lots of people had suspicions but nobody was telling.

No one took advantage of the conditions quite like Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax.

From 1962 through ‘66, the Dodgers won three pennants (and almost a fourth) and two World Series. Koufax, the Brooklyn-bred bonus baby who needed seven seasons to conquer his wildness, was 111-34 in those five seasons. Drysdale, who was signed out of the San Fernando Valley and joined the Brooklyn club in 1956, was 98-69 during that stretch.

The Dodgers developed a personality that played into the ballpark’s characteristics: Great pitching, solid defense, and speed on the basepaths to compensate for a paucity of power (though Frank Howard did hit 31 homers in the stadium’s first season). That pitching/defense/speed style got the Dodgers to 102 victories, one fewer than they needed, in ‘62. That was the year Maury Wills set the stolen base record with 104 (beating Ty Cobb’s 96), hit .299 with 130 runs, 208 hits and a 99 OPS+ -- below league average, thanks to a slugging percentage in the .370s -- and won the National League MVP award. Tommy Davis, with his .346 batting average and 153 RBI, finished third in the MVP race.

Koufax developed a numbness in the index finger of his pitching hand in May, which only got worse. It was reported that he had a mysterious ailment called Reynaud’s Phenomenon, yet Koufax noted in his 1966 autobiography that if that were the case it would have been a permanent condition and he probably wouldn’t have been able to pitch again. More accurately, he was hit on the left hand while batting, and a blood clot developed. It finally was treated, but then an infection in the finger developed which also had to be treated. The upshot: Koufax went more than two months between starts, from July 17 to Sept. 14, and Dodger fans of that era were convinced his absence cost their team a date with the Yankees.

And while Stan Williams was the guy who walked in the winning run in that deciding playoff game against the Giants, some Dodgers players of that era said that maybe that blame should have shifted to the guy who made the pitching choice in the ninth inning.

The background: The Dodgers led 4-2 going into that ninth inning, and Ed Roebuck had pitched two strong innings in relief but started the ninth by giving up two singles and two walks sandwiched around a force play, which could have been a double play had second baseman Larry Burright not been shifted so far to his right. Willie Mays’ single cut the Dodger lead to 4-3 and left the bases loaded, and Roebuck was just about out of gas.

Don Drysdale, who went 25-9 and wound up winning the Cy Young Award, was available. But as Duke Snider related in “True Blue,” Steve Delsohn’s oral history of the L.A. Dodgers. “I’m sitting next to Drysdale on our bench. I said, ‘What are you doing here? Go tell Walt you’ll warm up and pitch the ninth inning.’ Drysdale talked to Alston and came back. I asked him what Alston said. He said, ‘Walt said I’m pitching against the Yankees tomorrow in the World Series.’ I said, ‘If we don’t win, there is no World Series.”

Maury Wills suggested that Alston didn’t put Drysdale in specifically because “Durocher got real vocal in our dugout. He kept saying that Drysdale should go in. Well, Alston didn’t like that it was Durocher’s idea and not his. So he kind of cut off his nose to spite his face.”

So in came Williams. Orlando Cepeda flied to right to score the tying run. Williams intentionally walked Ed Bailey to load the bases, and then walked Jim Davenport on five pitches to force in the go-ahead run. Ron Perranoski replaced Williams, but by then the Dodgers had pretty much unraveled. Burright’s error on Jose Pagan’s ground ball allowed the sixth run to score before Perranoski struck out Bob Nieman to end the disaster of an inning.

“I was very peeved when he went with Stan Williams,” Tommy Davis told Delsohn. “I love Stan and I thought he was a great pitcher. But if you had Stan Williams or Don Drysdale, who would you bring in? So I started yelling at Alston, ‘You stole my money!’ I said it loud enough for anyone to hear. But there weren’t any reporters in there yet, because they didn’t open the clubhouse right away. Hell, no, they didn’t open the clubhouse. It would have been an Enquirer situation.”

They didn’t open it for an hour. From what we can tell, nobody said anything inflammatory to reporters in the clubhouse. But later Durocher was quoted as saying he would have done it differently, and Bavasi was ready to fire him right then until Alston talked him out of it.

It never all hinges on one game, of course. Another incident that helped change the course of that season took place on Aug. 10 when the Dodgers visited Candlestick to start a three-game series, bringing with them a 5½-game lead. Giants’ manager Alvin Dark suggested that head groundskeeper Matty Schwab find a way to put the brakes on Wills.

Schwab, the Giants’ groundskeeper dating back to the Polo Grounds, and his son Jerry quickly went to work in the pre-dawn hours of the series opener. According to their own description in a 1988 Sports Illustrated story, they dug up the topsoil in a patch about 5 feet by 15 feet at the beginning of the basepath between first and second, laid a swampy mixture of sand, peat moss and water, and covered it with an inch of infield soil.

“We were installing a speed trap,” Jerry Schwab recalled.

Not surprisingly, it was Durocher who first noted something was amiss the next day during batting practice and started digging the basepath up with his cleats. while first baseman Ron Fairly was building sand castles. Umpire Tom Gorman saw the result, noted that the Giants’ ground crew had made themselves scarce when the Dodgers took the field, and summoned Matty Schwab to tell him that he was looking at a forfeit if he didn’t fix it.

He fixed it, all right. The groundskeepers dug up the mystery soil and hauled it away in wheelbarrows, then brought back filler … which turned out to be the same stuff with more dirt mixed in. “When we put it down a second time it was even looser,” Jerry Schwab said. Then they watered it … soaked it, actually, as the Dodgers howled from their dugout.

“What could you do?” Tommy Davis recalled later. “It was their park. They were going to get away with anything.”

The Dodgers lost that night 11-2, and protested to the league office. So in the dark of night the Giants’ groundskeepers removed the evidence, put regular soil back in that spot and watered it so heavily that the umpires ordered them to add sand, which had the same effect. The upshot: Wills didn’t steal a base in the series -- and got thrown out of Game 2 -- and the Giants swept and pulled to within 2½ games.

Durocher had reason to be suspicious, since Dark played for him and Matty Schwab was his groundskeeper in the Polo Grounds way back when. Where do you think they learned the effectiveness of such shenanigans?

The only consolation for a Dodger fan after the playoff meltdown was that the Yankees beat the Giants in seven in, fittingly, a rain-delayed 1962 World Series in which Bobby Richardson gloved Willie McCovey’s line drive to snuff out the Giants last rally in the ninth inning of Game 7. That line drive would be immortalized forever in the Peanuts comic strip on Dec 22, 1962. Charlie Brown, the alter ego of creator and Santa Rosa resident Charles Schulz, and Linus sat on a curb with dejected looks on their faces in the first three panels. In the fourth, Charlie Brown wailed, “Why didn’t McCovey hit that ball three feet higher?”

A month later, same strip, same curb, same dejected looks on the characters’ faces, only this time Charlie Brown wailed: “Or why couldn’t McCovey have hit the ball even two feet higher?”

But the next chapter of the historic Dodgers-Yankees rivalry was merely delayed, not denied. And when they got together the next October, there was nothing for any Dodger fan, or comic strip character, to regret.

Anyway, as Dodger fans of a certain vintage liked to remind their counterparts to the north, San Francisco went 15 years without a postseason berth (1972-86), didn’t get back to the World Series again until 1989 and went 56 years without winning one. Then again, Giants fans of more recent vintage have responded with memes featuring their team’s 2010, 2012 and 2014 Commissioner’s Trophies. Dodger fans didn’t have a response … until October of 2020.

Break out the brooms

The 1963 regular season came down to a series in St. Louis in mid-September. The Cardinals, with Stan Musial in his last season along with a group that included Bob Gibson, Lou Brock and Curt Flood and would win a World Series the following year, came into that series trailing the Dodgers by a game after having won 19 of their last 20.

Johnny Podres won the first game on a Monday night, with Perranoski getting the save. Koufax shut out St. Louis 4-0 the next night. And Dick Nen, making his major league debut, put himself into Dodger lore by hitting a game-tying homer in the ninth inning of the third game, a shot that cleared the roof of the right field pavilion in the original Busch Stadium (the former Sportsman’s Park, which was replaced in 1966). The Dodgers won it in 13, 6-5, to complete the sweep and remind the Redbirds who was who.

Those brooms came in handy again a couple of months later against the Yankees. Koufax set a World Series strikeout record with 15 in Game 1, which finished in the late afternoon shadows at Yankee Stadium, Podres -- whom New Yorkers surely remembered from the glory of 1955, when he won Game 7 over the Yankees for Brooklyn’s only championship -- won Game 2. Drysdale outdueled Yankee right-hander (and future author) Jim Bouton in Game 3 at Dodger Stadium, 1-0.

And Koufax beat Whitey Ford 2-1 in the decisive Game 4, in which Frank Howard and Mickey Mantle hit solo home runs -- Howard’s was the first in Dodger Stadium history to land in the loge, or second, level -- but the winning run was scored when Yankee first baseman Joe Pepitone lost an infield throw in the white shirtsleeved crowd. Would that happen today? Probably not. First of all, it wouldn’t be a day game. Second of all, nobody wears white shirts to ballgames any more, unless they’re home jerseys.

Koufax ultimately won both his first Cy Young and the National League MVP Award. Who’s who, indeed.

Here’s your run. Make it last.

The Dodgers did not come close to repeating in 1964. The Phillies had a 4½ game lead with six to play and blew it, with the Cardinals winning the pennant, then beating the Yankees in a seven-game World Series after which both teams let their managers go. Yogi Berra was fired by the Yankees, and the Cardinals’ Johnny Keane wound up replacing him in New York, just in time for the collapse of the Yankee dynasty.

The Dodgers’ highlight in ‘64? Koufax pitched his third no-hitter in Philadelphia June 4. Drysdale, sent ahead to New York to get his proper rest before his next start against the Mets, heard the wrapup on the radio and the announcers talking about a historic third no-hitter, and is said to have blurted: “I don’t want to know about history. Who won?” That’s how light-hitting the Dodgers were.

But the Dodgers won again in ‘65, banjo hitters and all. How weak was the offense? Drysdale led the team in hitting (.300) and hit seven home runs, and is the first pitcher I can remember who hit higher than ninth in the order: Aug. 15 at Pittsburgh, with Drysdale batting seventh, catcher John Roseboro eighth and shortstop John Kennedy ninth. (Drysdale was 0 for 2 that game, but -- back in the No. 9 spot -- homered off Warren Spahn in his next start at San Francisco.) But why wouldn’t you hit Big D seventh? The Dodgers -- the eventual champs, mind you -- finished seventh in the National League in batting average (.245) and 10th out of 10 teams in home runs (78).

Of course, you can say the Dodgers were ahead of their time in another sense that season. The bullpen game? No, the smart guys who run the Tampa Bay Rays didn’t invent it in the 21st century. The Dodgers did it on Sept. 4, 1965, with screwballing reliever Jim Brewer starting and going 3⅓ innings, followed by normal starters Podres (4 innings) and Drysdale (⅔) and reliever Perranoski (1). (Nor did they invent it, either. The Washington Senators used a right-handed “opener” in Game 7 of the 1924 World Series against the New York Giants and went on to win that game in 12 innings. It was the District’s only World Series championship until 2019, when the Washington Nationals knocked off Houston, and you’ll find out why that’s a painful reminder in Chapter 29.)

The 1965 Dodgers boasted the majors’ first switch-hitting infield: Wes Parker at first, Jim Lefebvre at second, Maury Wills at short and Jim Gilliam at third. But that wasn’t enough to light up the scoreboard or even make the victories comfortable ones. Those Dodgers were 32-28 in one-run games, and were shut out six times but shut out their opponents 23 times.

That season also brought an unlikely hero. Tommy Davis broke his leg sliding into second base in May, and the Dodgers called up Louis Brown Johnson, a career minor leaguer, from Spokane to take his place. Sweet Lou provided a jolt of energy and enthusiasm -- he’d applaud himself rounding the bases after a home run -- while holding down left field and providing some key hits.

There was an afternoon of ugliness when the Dodgers-Giants rivalry turned violent on Aug. 21 in Candlestick Park. Roseboro buzzed Juan Marichal with a throw back to the mound in the third inning, partly in response to a couple of Dodger hitters getting low-bridged and partly in recognition that Koufax wouldn’t go high and tight. Marichal turned around and clubbed Roseboro in the head with his bat, triggering a melee and getting himself fined $1,750, then a record, and suspended for nine days (effectively two starts). Dodger fans complained Marichal got off lightly, but the Giants were 3-10 in that eight-day stretch, and Marichal was 3-4 with a 3.55 ERA in nine starts post-suspension, way off of his norm.

Roseboro sued Marichal for $100,000 in the immediate aftermath of the melee, but the two eventually settled the lawsuit, settled any differences they had and ultimately became friends. And a decade later, after 13 years of tormenting the Dodgers as a Giant and a brief stint with the Red Sox, Marichal signed with the Dodgers in spring training of 1975. He was released after two starts, but while the sight of Marichal in a Dodger uniform was weird, he didn’t get booed by Dodger fans, which sort of upheld a franchise tradition.

Brooklyn Dodger fans were able to welcome ex-Giant Sal Maglie with few hard feelings when he joined the Dodgers in 1956. It helped that Maglie, a principal combatant in beanball wars between the clubs, had gone to Cleveland first. It also helped that Maglie went 13-5 with a 2.87 ERA in 28 starts for the Dodgers and helped them win the 1956 pennant.

(We will never know if 21st century Dodger fans would have been so quick to bury the hatchet. When the Giants’ Madison Bumgarner was a free agent after the 2019 season and there was talk that the Dodgers might be interested, the tenor of the fan base -- or at least that portion of it active on social media -- was most certainly not welcoming. Bumgarner eventually signed with Arizona instead.)

We do know this: Roseboro helped campaign for Marichal to get into the Hall of Fame, which he did in 1982. And when Roseboro died in 2002, Marichal said at his memorial service that Roseboro “forgiving me was one of the best things that happened in my life . . . When I became a Dodger player, John told all the Dodger fans to forget what happened that day. It takes special people to forgive.”[11]

An overnight sensation … seven years later

Koufax might have been considered a comet in baseball’s constellation -- here suddenly, brilliant, and then gone -- but for the seven seasons he struggled to master his craft. Signed as a bonus player in 1955 and forced under the rules at the time to spend the entire season on the major league roster, Koufax never spent a day in the minor leagues but consequently never had an opportunity to truly develop as a pitcher. His was a life of mop-up duty, spot starts, occasional flashes of potential but more often periods of failure and frustration.

In fact, Koufax had almost convinced himself to hang ‘em up after the 1960 season, when he was 8-13 with a 3.91 ERA. He took one glove and one pair of spikes when the season ended, “in case I wanted to play softball in the park on Sunday afternoon,” he said, and told clubhouse man Nobe Kawano to dispose of the rest. After two weeks of Army reserve duty at Ft. Ord, he started work as a manufacturer’s representative for several electronics companies. But as spring got closer, he had a change of heart and decided to give it one more year.

The legend, which is accurate, is that Koufax finally, definitively figured it out during a spring training B game in 1961 in Orlando against the Minnesota Twins. Norm Sherry, his roommate and also his catcher that day, provided a lesson that would stick the rest of his career. Koufax, in his 1966 autobiography “Koufax,” written with Ed Linn, said Sherry told him:

“All this is, is a B game. You haven’t a thing to lose, because none of the brass is going to be there. If you get behind the hitters, don’t try to throw hard, because when you force your fastball you’re always high with it. Just this once, try it my way like we’ve talked about. If you get into trouble, let up and throw the curve and try to pitch to spots.”

“I had heard it all before,” Koufax continued. “Only, for once, it wasn’t blahblahblah. For once I was rather convinced that I didn’t have anything to lose. There comes a time and place where you are ready to listen.”

And, he noted, it wasn’t a matter of throwing any less hard: “I was trying to throw the ball as fast as, or maybe even faster than ever, but I was trying to go about it without pressing. I was still throwing hard, in other words. I was just taking the grunt out of it.”

To that point, Koufax was 36-40 as a major league pitcher and hadn’t exactly convinced his bosses that he was ever going to get it done. He was 18-13 with a 3.52 ERA in 1961, his first season as a regular in the starting rotation, and he amassed 269 strikeouts -- then a major league record -- in the National League’s last 154-game season. We have discussed his 1962 (14-7, 2.54, 216 strikeouts in 184⅓ innings of a season interrupted by injury) and his 1963 (25-5, 1.88, 306 strikeouts to break his own record, 11 shutouts, 0.87 WHIP, Cy Young, MVP, etc.).

The team struggled in 1964, but Koufax was 19-5 with a 1.74 ERA and seven shutouts, plus that third no-hitter mentioned above. But toward the end of that season he developed swelling in the elbow so severe, he wrote, “the whole arm was locked in a sort of hooked position.” Years later, Vin Scully described it as looking like a comma. Ultimately, the injury was diagnosed as traumatic arthritis, and after another instance of extreme swelling the following spring the condition was announced to the public.

Cortisone injections helped, as did liberal use of Capsolin, a balm made from the extract of hot peppers that was so hot players knew it as “Atomic Balm.” And Koufax iced down his elbow after every outing, an innovation then and now a routine part of a pitcher’s day. Koufax wrote in his autobiography that he also pared back his routine between starts, with the idea that if that didn’t work he might have to work every fifth day (pitchers went every fourth day in that era) or, if all else failed, once a week.

Early in the 1965 season, as Koufax recalled in his autobiography, rather than being worried “it would be more accurate to say that I was curious. I’d had a whole winter, after all, to accommodate myself to the idea that I might be in permanent trouble. If the elbow did blow up after every game, I felt that Dr. (Robert) Kerlan (the Dodgers’ team physician) could handle it. More than anything else, I simply wanted to know how I was going to go through the season, the hard way or the easy way.”

Perfection

That is the background for not only another Cy Young Award season (26-9, 2.04, 27 complete games and eight shutouts in 41 starts, a record 382 strikeouts in 335 ⅔ innings and an 0.85 WHIP) but arguably the best pitched game ever, on both sides.

Koufax pitched a perfect game and his fourth no-hitter against the Cubs on Sept. 9, 1965, just the eighth perfect game in history to that point and one that set a record for career no-hitters that lasted until Nolan Ryan broke it in 1981. He won a duel with Bob Hendley, who allowed only a bloop double by Lou Johnson that floated just over Ernie Banks’ glove and into short right field in the seventh inning -- a hit that didn’t factor in the game’s only run.

The game was decided by a typical ‘60s Dodger rally. Johnson walked in the fifth, was sacrificed to second, stole third and came in to score when rookie catcher Chris Krug’s throw went into left field. Johnson’s slide knocked third baseman Ron Santo down as the ball sailed over his head.

“The throw was high, but if Ronnie had stayed up he would have gotten it,” Krug recalled in an interview 50 years later, adding that the throwing error “probably brought me more fame than if I’d thrown him out.”

It was an unlikely duel between the venerable Koufax and the little known Hendley, recently recalled from Class AAA. who went into the game 2-2 on the season and 37-40 for his career. He struck out three but threw just 77 pitches in eight innings, successfully pitching to contact with 12 ground ball outs.

Koufax struck out 14, including the last six men he faced. This was a game, he later said, where “I didn’t have any particular stuff at the beginning of the game. Just average. I was throwing mostly curves through the early innings. In the last half of the game, though, my fastball really came alive, as good a fastball as I’d had all year.”

Said Scully, when we talked in 2015: "You'd watch him pitch to the first hitter or the second hitter, and a lot of nights you'd think, 'Whoa!' You'd see that fastball rise and that hammer curveball, and you'd think, 'Oh, my gosh, he might do it again tonight.' "

The Dodgers came into that rare single game on a Thursday night against the Cubs trailing San Francisco by half a game in the standings after two losses to the Giants earlier in the week. The Cubs, even with three future Hall of Famers in their lineup in Ernie Banks, Billy Williams and Ron Santo, were 15 games out of first place.

The signs were there from the start. Koufax got Don Young to pop up on the second pitch and struck out Glenn Beckert and Williams looking. He would have at least one strikeout in every inning. He threw 113 pitches, though pitch counts in that era were generally ignored. In modern ball, if a starting pitcher goes six innings and allows three runs or fewer it is officially credited in the stats as a "quality start." You did that in 1965? You were a slacker.

"When people try to compare Koufax and (modern-day Dodger ace Clayton) Kershaw, I say I really can't compare," Scully said. "Oh, yeah, they're left-handed, and they're both marvelous. But they're totally different."

Koufax had plenty left in the tank at the end. In the eighth inning, he struck out Santo looking on a 1-2 pitch and got Banks and Byron Browne swinging.

Krug led off the ninth, having flied to center on a 2-2 pitch to lead off the third and grounded to short on a 2-2 pitch leading off the sixth, on a throw by Maury Wills that first baseman Wes Parker had to dig out of the dirt.

"I was intimidated by the name, but as far as facing him, I wasn't intimidated," said Krug, who played parts of three seasons with the Cubs and San Diego Padres. "I couldn't wait to get up and hit."

Krug worked Koufax for a seven-pitch at-bat, only the second hitter of the night to do so (Banks, in the fifth, was the other). He fell behind 0-2, took a pitch high for a ball, fouled off two pitches, and took ball two, also high.

"The next pitch was a fastball," he recalled. "I can see it today. It was about (as) big as a balloon. I don't know how I missed it. I swung and missed. And I figured I was a part of history."

Joe Amalfitano, a veteran infielder who would years later be Tom Lasorda's third base coach in Los Angeles, came up as a pinch hitter for Don Kessinger and went down swinging on three pitches. That brought another veteran off the bench, Harvey Kuenn, who had made the final out in Koufax's second no-hitter against the Giants in 1963.

"Harvey said to Joey (as they passed), 'I'll be right back,' " Scully said.

It didn’t take long. And Scully’s description, on radio, was every bit as memorable as Koufax’ performance. In fact, any Dodger fan who was around then -- and plenty of Dodger fans who are younger but have heard the recording -- can recite the call of Sandy’s final pitch that night from memory, right down to the cadence and sing-song delivery:

In fact, the entire play-by-play of that ninth inning, which lives on via YouTube, could be considered an example of narrative literature. It was all ad-libbed, naturally, but the transcript -- grammatically precise as well as taut and gripping drama -- was reprinted word-for-word in "The Third Fireside Book of Baseball," a 1968 anthology compiled by Charles Einstein.

The description was as classic as the pitching performance, from start …

"Three times in his sensational career has Sandy Koufax walked out to the mound to pitch a fateful ninth where he turned in a no-hitter. But tonight, September the ninth, 1965, he made the toughest walk of his career, I'm sure, because through eight innings he has pitched a perfect game ..."

… to finish.

“It is 9:46 p.m. Two and two to Harvey Kuenn. One strike away. Sandy into his windup, Here’s the pitch … Swung on and missed! A perfect game!!”

Scully has told the story often: of how he tried to make the ninth inning call of any no-hitter, whether by a Dodger or an opposing pitcher, a little extra special -- adding the date, for example, so that pitcher could have the recording as a keepsake. Since Koufax had already thrown three no-hitters, he came up with the idea of adding the time of day.

"One and two the count to Chris Krug. It is 9:41 p.m. on September the ninth ..."

"I guess, because you never hear the time in baseball, for some reason it had a tremendous impact on the listener," Scully recalled in our 2015 interview. "Bud Furillo (of the Herald-Examiner), I think it was, wrote a column about how dramatic and exciting (including) the time was, and everybody was giving me a lot of credit for being a theatrical genius, or whatever. And I was totally oblivious. I was only putting the time on for Sandy."

"... Koufax into his windup and the 1-2 pitch: fastball, fouled back out of play. In the Dodger dugout Al Ferrara gets up and walks down near the runway, and it begins to get tough to be a teammate and sit in the dugout and have to watch … And Koufax with a new ball, takes a hitch at his belt and walks behind the mound. I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world ..."

"I remember, (it was) very dramatic with a big crowd, and because it was radio I really tried to describe the moment as best I could -- if Sandy sighed, if he ran his hand through his hair, if he dried it on his leg," Scully said. "Because it just kept building, and he was already a big star, a crowd favorite. So I tried really hard to capture the individual moment.

"I remember thinking, 'All right, bear down. He might do it.' "

The circumstances were far different then than they were, say, in 2014 when Scully called Clayton Kershaw's no-hitter against Colorado at Dodger Stadium. That night he did a TV-radio simulcast for the first three innings and TV only the rest of the way, and his description was accordingly spare.

"It's television," he said. "You're lookin' at it. I can't say, 'Oh, he's wiping his hand ...' It doesn't mean anything. And when he pitches the no-hitter, we say it (in progress) all the time. We don't hide it. So when he got the no-hitter I said, 'He's done it.' But what else can I say?"

"Sandy ready and the strike-one pitch: very high, and he lost his hat. He really forced that one. That's only the second time tonight where I have had the feeling that Sandy threw instead of pitched, trying to get that little extra, and that time he tried so hard his hat fell off -- he took an extremely long stride to the plate -- and Torborg had to go up to get it ..."

Scully acknowledged that with all the great baseball moments he has described, that broadcast might have been as special for him as the game was for Koufax.

"It was one of those rare nights, maybe the rarest of the rare," said Scully, who in his 67 years as a baseball broadcaster called 25 no-hitters and three perfect games -- by Koufax, by the Yankees' Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series and by Montréal's Dennis Martinez at Dodger Stadium in 1991. "As Sandy was doing a perfecto, maybe that night I came as close to being perfect, you know? That night, everything just fell into place."

"On the scoreboard in right field it is 9:46 p.m. in the City of the Angels, Los Angeles, California. And a crowd of 29,139 just sitting in to see the only pitcher in baseball history to hurl four no-hit, no-run games. He has done it four straight years. And now he's capped it. On his fourth no-hitter, he made it a perfect game. ...

"And Sandy Koufax, whose name will always remind you of strikeouts, did it with a flourish. He struck out the last six consecutive batters. So when he wrote his name in capital letters in the record books, that 'K' stands out even more than the O-U-F-A-X."

How can you top that?

Yet history, as memorable as it might be, also can be fleeting in baseball's day-to-day grind. Five days later, Hendley and Koufax faced each other again at Wrigley Field in Chicago. That day Hendley and the Cubs won, 2-1.

The assumption during that era, and especially after his retirement, was that Koufax didn’t play baseball as much as endure it. Physically that might have been true, but Koufax argued in his autobiography that the basis of that assumption, that he was somehow above it all, was way overblown. As is often the case, there was some nuance involved here.

“He liked to compete,” Scully said. “But he didn’t like all the to-do. And when people asked me the difference between Koufax and Drysdale, I’d say it was the difference between left and right.

“Sandy, if we’d go on the road and have a day game, he’d go to dinner with Dick Tracewski, a backup infielder, or Doug Camilli, the third-string catcher. Just the two of them would go quietly and have dinner. Drysdale, in the same circumstance, he’d have six or seven players with him. I mean, he was the Pied Piper. They all loved to be with him. Drysdale was extroverted and fun, and Sandy was quiet.”

An unorthodox championship

The Dodgers were in third place, 4½ games out of first, on Sept. 15 after losing to the Cubs in Wrigley Field. They didn’t lose again for more than two weeks. A 13-game winning streak, with Drysdale (4-0) and Koufax (3-0) accounting for more than half of the victories, put them up two with three to play. Koufax applied the clincher on the next-to-last day of the regular season in Dodger Stadium in what also turned out to be the next-to-last game ever played by the Milwaukee Braves, who would move to Atlanta for the 1966 season.

(Had the Braves stayed in Milwaukee, we might never have heard of Bud Selig, much less endured his term as Commissioner. Just a thought.)

Koufax did not pitch in Game 1 of the World Series in Minnesota because of his observance of Yom Kippur, an act that still resonates with those of the Jewish faith (and was recalled nearly four decades later when Dodgers outfielder Shawn Green faced a similar choice). Drysdale pitched that day and was hammered by the Twins, giving up seven runs in 2⅔ innings of an 8-2 rout, and lore has it that when Walter Alston came out to relieve him in the third inning, Drysdale is said to have cracked, “I bet you wish I was Jewish, too.”

Not that it mattered. The American League champions, who scored 774 runs and hit 150 home runs during the regular season, beat Koufax in Game 2 as well, 5-1. The Dodgers got back into the series at home when Claude Osteen, obtained with Kennedy the previous winter from the Washington Senators in the Frank Howard trade, pitched a complete game shutout in Game 3, a 4-0 victory. Osteen won 148 games in nine seasons as a Dodger, 147 in the regular season, but that Game 3 shutout was undeniably his biggest.

Drysdale then won Game 4, and Koufax took a no-hitter into the fifth inning of Game 5 before Harmon Killebrew’s leadoff single broke it up; he finished with a four-hit, 7-0 win. The Twins beat Osteen in Game 6 in Minnesota, 5-1, with Mudcat Grant hitting a three-run homer off Howie Reed in the sixth to break it open. Alston then had a choice for Game 7: Go with Drysdale on regular rest, or Koufax with two days’ rest and an elbow that barked and required countless shots of cortisone and a heavy slathering of Capsolin on days he pitched.

Alston went with Koufax, and Sandy was up to the task even though he was a one-pitch pitcher that day. He and Roseboro recognized early on that his curve wasn’t working, so Koufax went strictly to his fastball. Lou Johnson’s fourth inning home run off Kaat gave Koufax the only run he would need, Wes Parker added an RBI single later in that inning, and third baseman Jim Gilliam’s diving stop of Zoilo Versalles’ grounder and force out in the fifth helped choke off a Twins’ threat. Sandy did the rest, shutting out the Twins on three hits, 2-0, for the Dodgers’ third World Series title in L.A.

Who could have imagined this was the beginning of the end of a sensational era of Los Angeles baseball?

About the author:

Jim Alexander is a sports columnist for the Southern California News Group, which includes the Los Angeles Daily News and Orange County Register, and has covered sports in Southern California for more than four decades, including the Dodgers as a beat for 12 seasons and frequent columns about them in the years since.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.

Memory Lane was fun. I remember all of it. Except, of course, the Washington Senators opener. Slightly before my time.

Love this stuff Howie. But, so do you.

What a great title and fun jog through the Dodgers' early years in Chavez Ravine. I can still smell the cigars that many fans were smoking that somehow weren't all that bad at all.