Book Excerpt: God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen, by Mitchell Nathanson

Number 16 in a series.

With the World Series in Philadelphia for the World Series, it seemed like a good time to introduce you to a beautifully written book about Dick Allen. Originally published in hardcover in 2016, it is “God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen,” by Mitchell Nathanson (University of Pennsylvania Press, Paperback, 2019, $26.50, Kindle $14.31).

While my excerpt series is generally centered around new books, the objective is to feature interesting works about compelling topics. “God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen” is one such work.

As you might expect, the section I chose to excerpt covers Allen’s 1971 season in Los Angeles, and begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

After the excerpt you will find the usual Off Base sections, ICYMI, Tweet of the Week (which is a good one), Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

Chapter 10: Public Relations Men, Not Ballplayers: 1971: Los Angeles .295/23/90

‘‘AUGIE BUSCH NEITHER forgets nor forgives,’’ wrote former Cardinal pitcher Jim Brosnan in his reflection on Dick’s time in St. Louis. Despite the 34 home runs and the 101 RBIs, Dick’s spring training holdout irked the Cardinals’ owner, and he peddled Dick to the Los Angeles Dodgers shortly after the season ended. (Steve Carlton’s holdout lingered with Busch as well; the pitcher was exiled to Philadelphia at the conclusion of the following season, after he won 20 games.) Absent free agency, there was little Dick, or any player, could do about his employment situation; he could be ‘‘booted about like a football,’’ as journalist Doc Young wrote in an article about Tommy Davis’s travails with multiple clubs in 1970. Davis was painted as a malcontent and peddled three times within the space of a year. ‘‘The word ‘demoralized’ fits me to a T,’’ Davis said after the season. ‘‘I’ve been built up and let down, built up and let down, built up and let down.’’ So it was with Dick. ‘‘Think of Richie Allen,’’ wrote Jerome Holtzman after the 1970 season, ‘‘and it sounds like . . . trouble.’’ Busch had had enough of what he considered ‘‘trouble.’’ So he sent Dick packing.

For his part, Dick would have preferred to play another season in St. Louis, irrespective of the pressures he felt there. A couple of years later he said, ‘‘I wanted to stay there the rest of my career,’’ and while that might have been overstating things a bit, he certainly was not looking forward to packing up and shipping out so quickly after he had just arrived.

To Doc Young, Dick’s tenure with both the Phillies and the Cardinals demonstrated the need for free agency in baseball: ‘‘Baseball needs to—it should—revamp its reserve clause; a player should have an option, too. When Richie Allen wanted to get out of Philadelphia, he was locked in. When he wanted to stay in St. Louis, he was locked out. It’s a rather ridiculous scene, wouldn’t you say?’’ Busch’s treatment of Dick appeared to have softened Young’s stance toward him, at least somewhat. He would continue to criticize Dick from time to time but was beginning to realize that Dick was hardly the madman he was oftentimes portrayed to be (sometimes by Young himself). Upon his trade to the Dodgers Young wrote: ‘‘Los Angeles has begun to weave a welcome mat for Richie Allen, the baseball star. That’s good. Abused in Philadelphia, unceremoniously traded out of St. Louis, Richie deserves the goodwill of a major league city.’’

The trade itself was puzzling in multiple ways. That Dick was sent to the Dodgers, of all clubs, was surprising given the public statements about Dick that had emanated from the organization. Less than a year earlier Dodger vice president Al Campanis remarked, ‘‘When the Phillies made him available [after the ’69 season] we thought twice. We wanted his bat, but not his personality. We would have been making a travesty of everything that Dodger spirit represents.’’ Manager Walter Alston reportedly concurred, adding, ‘‘The day Allen walks in the clubhouse, that’s the day I pack.’’ Yet here Dick was, a Dodger. As soon as he arrived Alston backpedaled. When confronted with his earlier quote, he denied it. ‘‘I don’t know how these things get started,’’ the manager said. ‘‘I wouldn’t say anything like that about anybody.’’

Beyond that, the trade—essentially Dick was swapped for second baseman Ted Sizemore—simply didn’t make sense, baseball-wise. Sizemore was a handy player (he was even the National League’s Rookie of the Year in 1969) but was hardly a player of Dick’s caliber. Ray Shore, a Reds super scout, couldn’t believe the trade when he heard the specifics: ‘‘Boy, they like to have given him away, didn’t they?’’ he said. Even Dick’s harshest critics in Philadelphia were stunned: ‘‘Why the giveaway?’’ asked Frank Dolson. In the Sporting News, Melvin Durslag wondered aloud what was going on: ‘‘Outwardly he was no problem in St. Louis, which leads people in the sport to wonder why the Cards would trade a batsman of this quality for two lesser players [the Dodgers also threw backup catcher Bob Stinson into the deal].’’ According to the St. Louis beat writers, although the Cardinals were largely biting their tongues, they moved Dick because, as some of his teammates had whispered, ‘‘The Cardinals lost games and team unity.’’ One writer confronted Cardinals’ GM Bing Devine directly: ‘‘In other words, Bing, you got rid of Richie because you feel everybody has to arrive at the park at the same time. You feel there should be no special treatment for one player. No double standard.’’ Devine refused to confirm this, but to many within the press, he didn’t have to: the trade spoke for him. A story in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat alleged as much. In an article framed by an eight-column headline blaring ‘‘Cards Peddle Allen to Help Team Morale,’’ beat writer Jack Herman made his case that Dick was a disruptive influence on the club, and as such, it was more important to the Cards to rid themselves of him than to acquire equal value in return. Dick responded the next day: ‘‘These were grown men I was playing with. How could I hurt their morale? If I couldn’t have helped the club I’d have just packed up and left.’’ Dick’s friend Jose Cardenal was miffed at the deal and even decades later had trouble making sense of it: ‘‘They traded him for nothing. I have nothing against Ted Sizemore, but how do you trade a power hitter like [Dick], a superstar, for a singles hitter? I think they just wanted to get rid of him.’’

In many ways it seemed as if Dick was headed into a hornet’s nest in Los Angeles. Although Alston walked back his earlier remarks about cohabitating with Dick in the Dodger dugout, he stopped short of rolling out the red carpet for him. ‘‘I kind of felt we needed pitching more than hitting myself, to be honest with you,’’ he said the day after the trade. Regardless, like the Cardinals before them, the Dodgers seemed to go out of their way to preach to their fans that the Dick Allen they were acquiring was hardly the Dick Allen they had heard so much about when he was in Philadelphia. ‘‘As far as we know,’’ said Alston, ‘‘his behavior has changed considerably . . . he seemed like a different fellow [in St. Louis].’’ For his part, Dick was resigned to the reality of the nomadic baseball life to which he seemed destined. ‘‘I guess I won’t last long in Los Angeles either,’’ he said morosely in the wake of the trade, adding shortly thereafter, ‘‘Once you’re traded the first time, you’re a marked man.’’ Several months later he admitted that the trade hurt him deeply: ‘‘I don’t care how you say it, but when you’re traded, somebody didn’t want you.’’ Alston’s lukewarm welcome didn’t make things any easier for him.

Doc Young saw the trouble brewing almost immediately: ‘‘I wonder about the deal now because Allen is being brought, probably against his will, into a potentially nasty situation. And, if the deal goes bad, regardless of how innocent Allen may be, he’ll probably be made the scapegoat for it.’’ Young saw three potential areas of trouble as they related to Dick and the Dodgers: (1) his salary negotiations; (2) the Dodgers’ affinity for their current first baseman, Wes Parker (a Gold Glover with a mediocre bat who, Young feared, might displace Dick at first and therefore cause Dick to be exposed defensively at third or in the outfield, where he’d be subjected to abuse); and Walter Alston. Although he wished Dick well, Young wrote that the Dodgers were hardly the ideal situation for him: ‘‘If Richie Allen could have ‘played out his option’ in Philadelphia, most probably he wouldn’t be carrying that ‘bad boy’ tag today.’’ He would also be somewhere other than with the Dodgers, Young believed.

Just as he had in St. Louis, Dick put on a good face in front of the Los Angeles media: ‘‘Coming to Los Angeles is like coming to the major leagues. Everyone wants to play for Walter Alston, and I like Dodger Stadium, too.’’ The trade was ‘‘a dream come true,’’ he stressed. ‘‘I guess about every little Black kid in America who ever picked up a baseball bat—his favorite team was the Dodgers. I know it was mine when I was coming up as a kid. The Dodgers were the first team to have Blacks—to allow Blacks to play in the majors. This is where I really wanted to be when I first signed up in baseball. I finally made it.’’

Still, Dick hadn’t signed his contract yet, and regardless of his public statements he wasn’t planning on joining his new team until he was satisfied financially. Los Angeles sportswriter Melvin Durslag predicted fireworks in the upcoming negotiations: ‘‘As general manager of the Dodgers, charged with bringing Allen to gaff, Al Campanis suspects that Richie may not like spring training, which isn’t entirely the truth. He may like it for $155,000 but not for eighty-five.’’ Campanis offered Dick a contract calling for the same salary he had with St. Louis. Dick was seeking considerably more. As for whether he planned to show up on time for spring training, Dick remarked, ‘‘That’s something Mr. Campanis can arrange very easily.’’

Journalists’ predictions notwithstanding, the negotiations were surprisingly quick and amiable; in late November Dick signed for $105,000. He beamed when the agreement was announced: ‘‘This is the earliest I’ve signed. It’s also the best contract I’ve ever been offered and I couldn’t be happier. I’ve always wanted to be a member of the Dodgers.’’ He seemed to be itching to get his Dodger career off the ground: ‘‘Now that I’m out here, I see that color doesn’t mean a thing. It’s how well you play.’’ And he went out of his way to defuse the Wes Parker situation by stating that ‘‘if the man (Alston) wants me to catch, then that’s what I’ll do. Left field is fine with me. Anyplace is fine with me.’’ Parker, as well, was working on defusing any tensions. ‘‘Every time I look at Richie I see a World Series check,’’ he said. Dick refused to second Parker’s boast: ‘‘No predictions, my man. I leave predictions to Muhammad.’’

Dick was determined to get off on the right foot. He announced that he would be moving his family to Los Angeles and agreed to participate in the club’s optional winter workouts in late January. A few weeks later he even played in an exhibition game the Dodgers scheduled against the University of Southern California. Thirty-one thousand fans showed up to Dodger Stadium in mid-February to watch Dick take batting practice—a record for the event. They gave Dick repeated ovations when he stepped on the field, took his swings in the cage, and knocked one out of the park off Claude Osteen. In the five-inning game that followed, he grounded out. Regardless, the crowd left satisfied.

The next week there Dick was, in front of his locker, dressing for the season’s first spring training workout. ‘‘For the first time in a long time,’’ he said, ‘‘I know I don’t have to run and hide every time the door opens. I have this beautiful feeling that the players and people of Los Angeles are anxious to accept Rich Allen, ballplayer.’’ In an about-face, he extolled the value of spring training: ‘‘Spring training is a serious thing. This is your job and you have to tear yourself away from the rest of the world for six weeks. If you care anything about what you’re doing, it’s worth it.’’

A few weeks later he begged off a bit: ‘‘I’ve probably overdone it. I mean all the extra hitting is what I wanted to do, but when people took such delight in it, I probably did more than what was good for me.’’ He went to Alston and asked for a few days off. Alston acquiesced. A few days later, while shagging balls in the outfield, Dick crashed into a palm tree while going full-out and was knocked unconscious. He was unable to get up and was rushed to a hospital where he was diagnosed with a mild concussion. Although there was speculation that this would cause him to miss Opening Day, he was determined to return in time to make his debut with his new teammates.

Although the organization had reservations about signing Dick, the club desperately needed his bat. In 1970 the Dodgers hit only 87 home runs, the fewest in all of baseball, and had rarely shown much power since moving into Dodger Stadium in 1962. In their nine seasons there they had out-homered their opponents only three times. ‘‘Our club needs two or three hits to accomplish what the opposition accomplishes with one swing,’’ Campanis said. So, despite his misgivings, the GM pulled the trigger on the deal. While he was concerned about the club’s image within a public relations context, its image among its baseball brethren, as well as with baseball fans overall, was that of a Punch-and-Judy ball club. ‘‘Perhaps,’’ wrote Bob Hunter of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, ‘‘it will be . . . Rich Allen who, at long last, changes the image of the Dodgers.’’ So it was that Dick was greeted with thunderous applause whenever he stepped up to the plate at Dodger Stadium in the early going. When he hit his first home run of the season—a monstrous blast well over the centerfield fence—everyone wanted to show their appreciation for the man they believed was going to single-handedly turn the Dodgers around: ‘‘They greeted him enthusiastically in the dugout,’’ Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times wrote the following morning, ‘‘but that reception paled in comparison to the standing ovation tendered by the fans.’’

On the whole, the media’s reception of Dick in Los Angeles was far more benevolent than anything he had received in Philadelphia, and even more generous than what he experienced in St. Louis. While the St. Louis media trumpeted the ‘‘Richie has changed’’ theme throughout 1970, the Los Angeles media, although striking the same tune to a degree, also challenged the notion that Dick was ever as bad as he had been made out to be. ‘‘The one thing I want to get across,’’ Dick told a Los Angeles Times writer a few years later, ‘‘is that I never try to make people like me. I just want people to appreciate what I’ve done, that’s all.’’ ‘‘He was the type of player,’’ added Alston, ‘‘who couldn’t be told, ‘You be at the park three hours early or I’ll fine you $1,000.’ But if you asked him to come early in a decent way, he’d show up 10 minutes before everybody else.’’ If approached with respect he’d respond respectfully.

More folks in Dick’s world were now keen to this reality, and his relationship with the media and management appeared to thaw somewhat. ‘‘[His teammates] all felt he was a terrific guy . . . they liked him, I think the reporters liked him, he got along with the press as I recall,’’ remembered the Los Angeles Times’ Ross Newhan. In the Los Angeles Sentinel, Doc Young’s skepticism soon gave way to outright support; now exposed to him up close for the first time, Young embraced Dick as never before: ‘‘With the trade to Los Angeles, he has been emancipated. More precisely, he has emancipated himself—just being himself: a naturally friendly man, a highly-intelligent, articulate man, a hard-worker, a man who loves baseball, a man who has come close to busting his bones for the ball club. His reward, despite an early-season slump, is tremendous fan-love. And great press notices. Richard Anthony Allen—great, gawd a’mighty—is free at last.’’

Not all was as it seemed, however. Though Campanis agreed to pay Dick $105,000, the Sentinel alleged that he had no intention of raising the club’s payroll to do so; instead he asked the club’s unofficial captain, Maury Wills, to take a pay cut to offset Dick’s salary. And despite the club’s growing understanding of the importance of giving Dick his space, higher-ups were nevertheless irked at his refusal to engage in the club’s myriad public relations activities. ‘‘The Dodgers expected [Dick] to make an occasional appearance on behalf of their charitable wing, or they’d have autograph days at the ballpark and expect him to be part of them,’’ said Newhan. ‘‘Those kinds of things are bigger now than they were then,’’ he added, but still, to the Dodgers of the early 1970s, they were important. ‘‘We wanted to be an active, involved, concerned, caring member of the community,’’ recalled former Dodger president Peter O’Malley of that era. ‘‘That philosophy was explained to our management team, to the manager, the coaches, the major league ball club, the farm teams, [and to those at] the training site at Vero Beach.

It was a policy, a philosophy, of the organization. . . . Whenever we found that we explained to the players what we wanted to do and why we wanted to do it, the pushback was at a minimum. . . . Ninety percent, 99 percent of the players, when they were told [or were] asked about an occasion coming up, they were all in.’’

But not Dick. ‘‘My main interest was just playing baseball,’’ he said a few years later. ‘‘But they wanted me to run here and appear there when we weren’t playing. I knew I wasn’t ready to project that kind of personality yet. . . . The trouble is, I’m not comfortable in all the situations that baseball presents. I have to be my own man—I can’t perform as well when I have to be like somebody else.’’ For an organization that cherished its reputation as ‘‘baseball’s most image-conscious team,’’ that could be a problem. In 1972 Dick reflected on the pressures inherent in being a Dodger: ‘‘I couldn’t have taken it out there for another minute. The manager and the guys on the team were great, but it’s such a different scene out there. There are so many public relations demands, so many people to meet, so many distractions.’’ Contrary to the aims of the Dodgers’ public relations campaigns, he continued to bristle at the notion that ballplayers should be, or even could be, role models for children. ‘‘People buy a ticket to see you play; that should be all,’’ he said a few years later. ‘‘People idolize ballplayers. I don’t want to be idolized. There are too many things you got to get through before you get to the field. Let a kid idolize his father; maybe there would be less drug problems. . . . Even bubble gum is bad for a kid’s teeth.’’ As for the Dodgers, Dick became convinced that they believed that the off-field activities trumped the ones that took place on the diamond: ‘‘The Dodgers wanted public relations men, not ballplayers.’’

Bristle as they might, the Dodger brass understood, as the Cardinals did before them, to back off. Consequently, Dick’s refusal to follow the club’s promotional mandates didn’t result in the same eruptions in Los Angeles as they had in Philadelphia. At last Dick was starting to gain some traction in having his employer deal with him on his terms. In Philadelphia, he suffered the repercussions of his independent streak, but in Los Angeles things were somewhat different. Although the Dodger brass might have wished he participated more fully in the club’s off-field functions, they didn’t publicly malign him for refusing to follow along, nor did the fans or the writers find anything sinister in his determination to do things his own way. Slowly but surely, the winds in the conservative baseball universe appeared to be shifting.

By the early 1970s Dick began to have some followers along his independent path, most notably Reggie Jackson in Oakland. Jackson refused to attend certain team functions as well (such as the club’s midseason picnic at owner Charlie Finley’s ranch), and though Finley ordered him benched for a time, he eventually gave in. Allen and Jackson both refused to be subservient to club management’s idea of how they ‘‘should’’ act. Both demanded that their opinions be heard and heeded. While the overwhelming majority of players still acceded to management’s wishes, a growing minority felt emboldened to go their own way. With each passing year, these players found incrementally more support among the public and working press, who increasingly came to realize that a player’s offfield habits and on-field performance could be two distinct things with one having little effect on the other. No two players demonstrated this changing sentiment more than Dick and Jackson.

Of course, both players were talented enough to compel management to deal with them on their own terms. Finley might be offended that Jackson refused to visit him at his farm, but there was no replacing his bat in the middle of the A’s lineup; once Finley recovered from his pique he had Jackson reinstated in the starting lineup where he would be the key element in the club’s three consecutive World Series championships in the early 1970s. Same with Dick—regardless of the level of O’Malley’s agitation with him there was nobody else on the roster who could supply the offensive firepower he could. Lesser talent would not command the same level of tolerance. Nevertheless, more players were stepping out than ever before, although they often paid a price for doing so: Lou Johnson, Oscar Gamble, Jose Cardenal, Dock Ellis, Mike Marshall, Vida Blue, Ted Simmons, and then, finally, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, who, in 1975, challenged the game’s reserve clause and brought the players free agency at last.

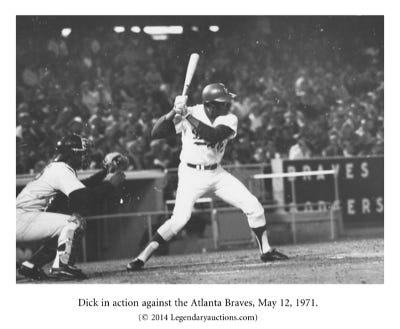

Ultimately, however, irrespective of a player’s talent, management still pulled the strings in the game’s pre–free agency era. The Dodgers might tolerate Dick now, but that didn’t mean they would tolerate him forever. Indeed, even before the season ended there were whispers that Dick’s time in Los Angeles was going to be brief despite the solid season he was having. And, true to Doc Young’s preseason fears, the club continued to stick by Wes Parker, who wound up playing 148 games at first, hitting .274 with 6 home runs. This was to Dick’s detriment, as he wound up splitting the majority of his time between third base and the outfield, where he struggled defensively but hit .295 with 23 home runs and 90 RBIs. As the season progressed, Young sensed that the Dodgers were trumpeting Parker much as the Phillies had trumpeted Callison a few years earlier: ‘‘Richie started the season in left field. His best position was first base. But the Dodgers had Wes Parker playing first base and Wes Parker is highly touted as ‘Mr. Golden Glove’ and the publicity department was trying to sell him as baseball’s newest super star. Which he isn’t. Which is one reason why the Dodgers are lagging and sagging.’’

Parker was the polar opposite of Dick in many ways. In fact, he was such a management shill that the following season, when the players voted to strike, Parker (the Dodgers’ player representative) was the lone abstention. (The vote was 47–0–1 in favor of a walkout.) As Marvin Miller recalled, ‘‘Parker had been quoted several times as being opposed to players receiving ‘ridiculously high’ salaries (such as $150,000 a year); not long after the meeting he was removed from office by his teammates, who described their action as ‘impeachment.’ ’’ The Dodgers’ preference for company men was obvious: a couple of years later Steve Garvey would be the apple of their eye; they touted him as the ‘‘flawless Dodger’’ and were thrilled when he announced that he planned to spend his off-season studying that which Dick despised—public relations.

By season’s end, and despite the absence of overt turmoil, both sides realized that Dick Allen and the Los Angeles Dodgers were hardly a match. The problem with the Dodgers, as Dick saw it, ‘‘was all that Dodger Blue jive. Not Dick Allen style. The organization tries to get you to believe that being a Dodger is all you’ve ever needed in this world. They want you to feel blessed. It’s one way they keep their players in tow. A lot of guys fall for it.’’ Dick didn’t, and as a result, his year there fell far short of his preseason expectations. ‘‘Dick was never happy in Los Angeles,’’ his wife, Barbara, remarked the following year. As for why he wasn’t, she believed that, irrespective of everything that went right, it was the initial slights that trumped all else: ‘‘How can you be happy when the manager says he doesn’t want you?’’

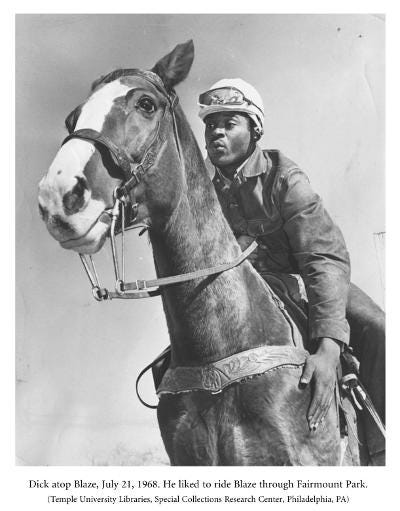

When things got tough for him in Los Angeles, when he felt pressured and stressed, Dick retreated to the stables where, for as long as he could remember, he had found comfort and solace. Indeed, it was the lure of the horses that convinced Alston that, despite his reservations, Dick might eventually take not only to Los Angeles and the Dodgers but to Alston, a horse owner, as well. ‘‘I’m afraid that Rich may go Hollywood on me,’’ he told a gaggle of writers at a preseason banquet. ‘‘I don’t mean the movies, I mean the racetrack.’’ The proximity of Hollywood Park to Dodger Stadium offered Dick the opportunity for respite that Alston hoped would calm him through the storm of a frenetic season. While Dick hesitated to go to the track in St. Louis, Alston made it clear that it was not off limits with the Dodgers.

People often misinterpreted Dick’s affection for thoroughbreds. ‘‘It’s ridiculous the fuss they make about horses,’’ he said in May. ‘‘So many guys stand around the clubhouse talking about golf and reading golf literature in the clubhouse. I’ve never read horse racing literature in the clubhouse. So they knock my love of horses.’’ A few weeks earlier he had remarked, ‘‘When I go to a track, I’m combining relaxation with business. I don’t like to see a baseball player on a golf course. To me it reflects contentment. I get the same feeling when I see a player smoking a pipe.’’ Whenever he was spotted at the track, an issue would be made of it and an impression formed that fit the longstanding narrative of Dick as a troublemaker: ‘‘People who say they see Rich Allen at the $100 window aren’t telling the truth. I go to the track because I like the form, the breeding and the racing. I’m basically a $2 bettor. Maybe I’ll take a horse across the board. If I think I’ve got it figured out pretty good, I may go as high as $10. That’s it. During my baseball career I’ve simply been involved in too many hassles and lost too much money because of them to be able to afford throwing it away at the track.’’

As a child he loved his family’s horse and was heartbroken when his father sold it. ‘‘All he could think about was having another horse,’’ recalled his brother Hank. ‘‘He got a paper route and saved about $100 and he went off and found some old broken-down nag that he could get for $75. Well, naturally, mother wouldn’t let him do it—he was only a little kid—so he stomped around and finally said, ‘well, someday I’ll get me a horse.’ ’’ When he joined the Phillies he got that horse and had a few on and off from that point forward. ‘‘My big interest,’’ he said in 1973, ‘‘really is to see how big a heart a horse has. They’re just like athletes, even baseball players. You see a guy who’s maybe got a pulled muscle and he don’t want to play today. Well, there are horses, too, who won’t run with any little discomfort. Then there’s the one horse whose heart is as big as this room, who by the time he gets to the gate has forgotten all about any tender sore spot, whose mind is only on racing. He’s the one I watch.’’

By the time he had settled into his life in Los Angeles, Dick owned four horses and announced his intention to ‘‘have the biggest Black-owned stable in America.’’ ‘‘I’m going to breed thoroughbreds like the brothers, you know. I want to do this for my son. Horse racing is just about the oldest sport out and the Black man doesn’t get the credit for his efforts around horses. From my reading, I see that the Kentucky Derby has been won by a black jockey named Isaac Murphy [he won it three times—1884, 1890, and 1891]. You never hear anything about it.’’ In 1989 brother Hank became the first African American trainer of a Kentucky Derby entrant since 1911, and for years Dick would haunt the local racetracks. After his retirement he could sometimes be seen walking the grounds at Santa Anita, shaded by a Sherlock Holmes cap. ‘‘An old horse trainer from England got me to wearing these,’’ he said in 1983. ‘‘He told me that with the double bill, you’ll know where you’ve been and you’ll know where you’re goin’.’’

For years Dick spoke of his thwarted desire to become a jockey himself: ‘‘I wish I could weigh 115 pounds for a couple of hours in the afternoon and then go back to my own size at 5 o’clock. That way I could be a jockey and still play baseball.’’ Regardless, whenever there was trouble in his world he’d withdraw to his horses and could usually be found riding one. In Philadelphia he would deal with the swirl of issues that surrounded him by heading out to the Monmouth or Garden State racetrack or by riding his horse through Fairmount Park. In a world he felt to be spiraling out of control, horses provided him with a measure of calm and order: ‘‘[T]here’s a lot of phoniness in baseball and I can find relaxation around horses.’’ A little while later he added that ‘‘sometimes I feel like going back to the country to raise horses and do little thinking and no worrying.’’

Throughout his career Dick was repeatedly asked by a curious and oftentimes perplexed media to explain his fascination with horses and gave varying responses. At times he defined his interest in practical terms—they were his path toward establishing a business to sustain him and his family after his baseball days were finished—but at other times he’d speak more metaphorically. A horse is like a ballplayer, he sometimes said. ‘‘You put your money on the line to buy him and after that it’s all up to him. Either he’s worth what you paid or he isn’t.’’ After he retired he expanded on this point: ‘‘Racehorses and ballplayers—they’re bought, they’re sold, they’re traded. Today in this barn; tomorrow in somebody else’s.’’ They reminded him of some people he knew: ‘‘they’ve got very little brains, but a whole lot of sense.’’

Clem Capozzoli, like Coy before him, had Dick on a budget (by 1969 it was up to $35 per week), leaving Dick with little pocket money despite his large salary. As such, he was compelled to seek Capozzoli’s permission for any large purchases, such as horses to add to his stable. It was only after receiving Capozzoli’s blessing that he was permitted to purchase Trick Fire and three other horses in the spring of 1969, and he often let off steam by working with them or by simply watching them run. (Indeed, it was because he took time out on his way to Shea Stadium a few months later to watch Trick Fire race that he missed the doubleheader with the Mets that precipitated his indefinite suspension.) Heading into the 1970 season he sold two of his horses and transferred the title of a third to Barbara so as to quell the media’s speculation over his equinal interests. ‘‘I had to do it,’’ he explained shortly after doing so. ‘‘They [the Philadelphia writers] made it appear that I was more interested in racing than I was in baseball.’’ On this one occasion at least, he heeded the optics of the situation. Lesson quickly learned, however, as putting on this false face contributed to his unhappiness in St. Louis. When he arrived in Los Angeles, he reestablished his stable. He kept a pair of horses at Santa Anita and more on his farm, Sweetbriar Acres, in Perkasie, Pennsylvania. When asked why he chose to establish a stable in Pennsylvania and not Kentucky like most thoroughbred breeders he replied, ‘‘That’s the way I am. Everybody runs to Kentucky, I’ve got to go the other way. The trend-setter.’’

‘‘Loners don’t fit easily into the Dodger family,’’ wrote Jim Brosnan in 1972. ‘‘The Dodgers have the most tightly-knit, clannish organization in baseball.’’ An introverted, shy individualist like Dick never really had much hope of succeeding there in the long term. Here again he harked back to an earlier age in baseball: ‘‘A proud free spirit in a game that has grown increasingly uptight—a colorful throwback to giants such as Babe Ruth and Grover Cleveland Alexander, the hard-drinking, swashbuckling individualists of baseball’s golden age,’’ read a Newsweek portrait of him a few months earlier. But that sort of thing wasn’t going to fly with the Dodgers. As for why not, perhaps Maury Wills put it best: ‘‘The Dodgers are like a woman . . . to be loved . . . not understood.’’

Besides begging off on public relations requests, Dick reverted to his tradition of routinely skipping batting practice. He was not the only Dodger to do so, but the way he did it proved irksome. ‘‘Occasionally he would watch batting practice from the club level at Dodger Stadium,’’ recalled Newhan, ‘‘with a cup of something in his hand.’’ In early June he was benched for a game by Alston when he didn’t see Dick on the bench shortly before game time. Dick contended that he was in fact in the ballpark and in uniform but was chatting with a friend in a corridor between the clubhouse and dugout when Alston peered down the bench. Just prior to the game’s first pitch Dick arrived on the bench only to be informed that Bill Russell was taking his place in the lineup that afternoon. Alston covered for Dick after the game, reminding the beat writers that the game was unusual in that it was scheduled to start only fifteen minutes after the completion of an old-timers’ game and that ‘‘almost everyone was caught short.’’ ‘‘This whole thing will probably look worse than it really was. It was very unintentional on Allen’s part,’’ he said. When the reporters gathered around Dick’s locker, he expressed bewilderment over the issue: ‘‘I can’t see why this is being made into such a big deal. I actually appreciated the rest. Wes Parker ASKED for the night off yesterday and nothing was said about it.’’ A few months later he told the Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray, ‘‘This is a job. Only, you can’t call in and say ‘I think I’ll take the day off.’’’ If you did, particularly if your name was Dick Allen, you’d be expected to answer for it.

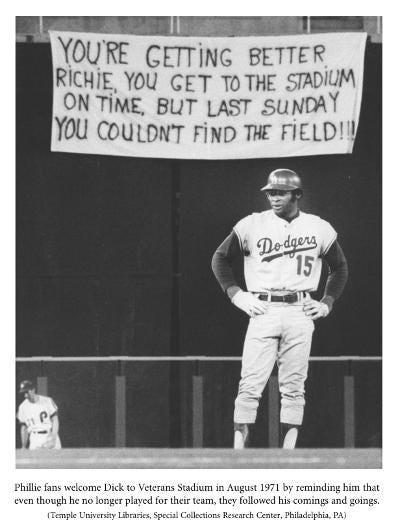

In so many ways Dick wasn’t the prototypical Dodger; at some point the decision was made to see how far he could take them in 1971 and then move on. ‘‘Late in the season, Alston had a meeting with several of his veteran players, asking them what they would do with Richie Allen,’’ Newhan recalled. ‘‘The consensus was that ‘he can help us. We’ll deal with it. Let him alone and it will play itself out.’ . . . The veterans told [Alston], ‘We can win with him,’ and they almost did.’’ (The Dodgers finished at 89–73, one game behind the San Francisco Giants in the Western Division.) There was also suspicion that Alston laid off when it came to Dick because he was good friends (and roommates) with centerfielder Willie Davis, who finished the season with a .309 average, an All-Star Game appearance, and a Gold Glove. In other words, Davis was in the midst of a fine season that Alston didn’t want to see come apart in the stretch run as a result of any dust-up between Dick and management. Late in the season there were a couple of other incidents—both involving his former teams—that further sealed Dick’s fate in Los Angeles. In the first, Dick arrived late to the ballpark for an August game against the Cardinals in St. Louis and was benched. Less than two weeks later he hit a mammoth home run in the Phillies’ new home, Veterans Stadium, that nearly hit the stadium’s replica Liberty Bell in dead centerfield. After being removed for a pinch runner in the eighth, Dick—perhaps dreading the inevitable horde of Philadelphia writers who would no doubt descend upon him once more, asking for his take on the blast among other topics—took off toward the clubhouse and was gone from the stadium before the game was over. ‘‘That made him even for the day,’’ ran the story in the next day’s Los Angeles Times, ‘‘as he had shown up at the stadium 15 minutes before game time, a fact that did not escape some of his teammates.’’ As the 1971 season began to weigh heavily on him, the prospect of returning to St. Louis and then Philadelphia, with all of the freighted media obligations that came along with those games, was perhaps too much for him. So he stayed away from the ballparks beforehand and then, in Philadelphia, took off as quickly as he could once he believed he had discharged his professional obligations on the field.

By the end of the season, Dick and the Dodgers had irreparably soured on each other. As for his teammates, he had few nice things to say about them: ‘‘The old Dodgers were my team, but these guys were a bunch of crybabies, always arguing with umpires and throwing their helmets. Maury Wills was hard to play with. Walt Alston treated me like a man, but he’d been quoted as saying he’d quit if they got me. Maybe he was misquoted, but he never said anything different to me.’’ As for the allegedly laid-back Southern California fans, Dick saw that, in the end, they were not all that different from the ones he had had to deal with in Philadelphia. ‘‘The fans [in Los Angeles] have the same problem as those in Philadelphia and other cities where the team isn’t winning,’’ he said shortly after the conclusion of the season. ‘‘Well, during these losing years, fans develop hostilities. They come to the park angry and frustrated. And they drink to forget about their team.’’

Reflecting upon the season in its final days, Dick concluded that as far as he was concerned, it was ‘‘money well-earned.’’ As for the specifics of his production as a Dodger, he demurred: ‘‘There’s too much attention put on batting averages and personal achievements. Why? Why should it be? If I go out and just try to bat .300 I could bunt and scratch around and protect my figures and forget about putting the ball in the air when it might mean a run or concentrate on hitting a home run when it doesn’t help anything but myself.’’ But how would management know who was producing and who wasn’t if the statistics could be deceiving? ‘‘They know,’’ he said. And when asked if he hoped to return to the club in 1972, he was nonchalant about it all: ‘‘We go where they tell us to go. We don’t have any say about it. If they want me, I’ll stay. If they don’t, I’ll go.’’77 To the Philadelphia Tribune he was more forthcoming. When asked if he was happy with the Dodgers, he shot back, ‘‘How in the world can a black man be happy when the manager and all the official representatives of the team are white?’’

In December he was traded yet again, this time to the Chicago White Sox in a three-team deal that brought the Dodgers Frank Robinson from the Orioles and Tommy John from the White Sox. According to the official Dodger line at the time of the trade, Dick was traded because first base was his best position, which made him expendable given the presence of Wes Parker (who would follow up his 1971 six-home-run campaign with four in 1972 and then retire). But the real reason he was moved— because of what the Dodgers thought he represented—emerged later. ‘‘After a lot of thought we reached the conclusion that our success through the years stemmed from a team spirit that ran right down to the clubhouse people,’’ said Campanis the following year. ‘‘We didn’t feel it was worth compromising our standards. From a long-range view we felt we could win more often with players who conformed to the rules.’’ Employing a player who seemed to signal that the Dodger Way wasn’t the only way was a bridge too far for them.

This wasn’t the first time that Dick’s nonconformist ways caused him to be shuffled out of town, but this time the reactions in both the white and black press were, on the whole, more critical of management than of Dick. In the Sentinel, Doc Young blasted the organization, writing that ‘‘it now seems true that, based on his past ‘reputation,’ the Dodgers decided to rid themselves of Allen long before he began to play his best ball for the team.’’ With regard to the Dodger higher-up who told Young, ‘‘You can’t have one rule for 24 players and another for a single player,’’ Young countered, ‘‘The question, or problem, of rules can be solved in one of several ways, all having to do with human understanding or leadership. With a player like Allen, you start with his desire to be a winner—and go from there. . . . Are the Dodgers so hung up on acquiring players who ‘won’t cause any trouble’ that they are handicapping themselves? I think that is a question Dodger executives should ask themselves. Not all great ballplayers are great gentlemen. Jackie Robinson was the most controversial player in the game; Duke Snider sometimes had problems as, admittedly, did Don Newcombe; Carl Furillo spent lots of time in his own peculiar bag and so it went. But the Dodgers won.’’ In a later column he was even more blunt: ‘‘The organization places too much emphasis on the so-called ‘nice guy’ image . . . [Walter] Alston, a decent human being personally, has lasted all these years as a Dodger manager not because he actually is as great as he is rated, but because he doesn’t give the front office any trouble.’’ Young’s tone was a significant shift from how critical he had been of Dick earlier. Seeing the interaction between Dick and his employer firsthand, Young was coming to the realization that Dick wasn’t the villain he had been made out to be. Instead, he was an individualist who was largely being punished for being himself. Perhaps, Young was finally starting to realize, the organizations played a larger role in Dick’s troubles than he had assumed.

The Los Angeles Times agreed. In 1972, after Dick won the American League’s Most Valuable Player award with the White Sox, the paper ran an editorial that eviscerated both the Dodgers and the venerated ‘‘Dodger Way’’: ‘‘The selection of Dick Allen as the American League’s most valuable player should give the Dodgers second thoughts. They traded the 30- year-old first baseman to the Chicago White Sox on the grounds he was a nonconformist whose ways hurt team discipline. In Chicago, manager Chuck Tanner used all the arts of persuasion—tact, friendliness, guile—to make Allen feel at home so he could play his best. It worked. The Dodgers . . . didn’t try hard enough or adroitly enough. Under Dodger-style reasoning, the Lakers should have traded Wilt Chamberlain and the New York Jets should have unloaded Joe Namath. They’re nonconformists, too.’’ Individualism, it was beginning to seem, was no longer a crime. Even the mainstream press was beginning to acknowledge that at last. As both Young and the Los Angeles Times’ editorial board signaled, it was now up to organizations, staid as they may be, to come to grips with this shifting reality and to learn how to acknowledge it in their dealings with their employees. Failure to do so, as the Dodgers’ on-field results over the previous few seasons seemed to indicate, would be to their ultimate detriment.

That the Los Angeles Times’ coverage of Dick throughout the 1971 season was markedly different from how the Philadelphia papers covered him just a few years earlier was evident in its handling of what, in previous years, might have been an explosive piece of information. In a December article detailing the trade, Newhan wrote of an earlier discussion he had had with club president Peter O’Malley: ‘‘On a warm night at Dodger Stadium last July, with the Dodgers a discouraging 10 games behind the Giants, president Peter O’Malley confided: ‘I’ve made up my mind that Allen will have to be traded. He’s been an unsettling influence on the club.’’’ In Philadelphia during the 1960s, this quote would have undoubtedly been front-page news the following morning. Newhan, though, decided to sit on it. Later, he explained his rationale: ‘‘When Peter O’Malley said Allen was a problem player and would be traded, the team was ten games behind the Giants. I felt to say anything about Allen then would have been unfair to him and would have given the appearance he was the reason the Dodgers were not doing well.’’ This, Newhan decided, would have been inaccurate: ‘‘Alston did not make a fuss about Allen, and the other players did not complain about Allen’s behavior off the field.’’ As Newhan understood the situation, Dick’s habits and the team’s struggles represented merely a correlation, not causation. To conflate the two, as those in Philadelphia had done, was to present Dick as the scapegoat. Newhan concluded that it wasn’t Dick’s arriving shortly before game time or not taking batting practice that caused the club to fall so far behind the Giants; myriad other, on-field and front-office, decisions and moves were the problem.

Two years earlier Dick told Sandy Padwe, ‘‘As far as I’m concerned, there’s too much emphasis on this Joe College approach [to baseball]. This is a professional sport, not a college sport. These guys . . . come in here and do the job they have to do. When the game starts, you pull together as a team; when the game ends, you go your own way as an individual.’’ As he had understood for years, there was something different about being a professional athlete. Although the fans and the media treated professional sports as games, the athletes themselves didn’t. They understood what it took to perform at their best and very little of it called for being the prototypical ‘‘team player.’’ One could be a productive member of a professional ball club and still retain one’s individuality. ‘‘Individuality is what you own; it’s who you are,’’ said Larry Christenson, a teammate of two staunch individualists—Dick and Steve Carlton. ‘‘Lefty did his thing. Dick did his. I was fine with it. It didn’t affect the locker room.’’ Professional athletes understood that being an individualist and a good teammate were not mutually exclusive. ‘‘Dick was one of my greatest teammates,’’ he recalled. ‘‘He was always rooting for you.’’ Whenever Christenson was going through a rough patch or suffering a crisis of confidence, he knew that Dick would be there to calm the waters. ‘‘I was just a kid,’’ Christenson continued. ‘‘He’d put his arm around me and say, ‘Hey kid, I’ll get you some runs.’ ’’ That was all the young pitcher needed to hear to collect himself and focus on the task at hand. After the last out, it was no sin if a teammate decided to go his own way. ‘‘You didn’t see him out to dinner,’’ Christenson recalled. ‘‘He had his own friends.’’ From one professional athlete to another, this was not a problem. As Jackson’s A’s were about to demonstrate, a successful club could be comprised of a whole locker room full of individualists who were also superior teammates. Dick had always known this. Finally, everybody else seemed to be catching up.

About the author:

Mitch Nathanson is the author of the first and only comprehensive biography of the mysterious slugger Dick Allen. In GOD ALMIGHTY HISSELF: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen, he revealed in full the man behind the myth. In his latest baseball biography, BOUTON: The Life of a Baseball Original, Nathanson tells the remarkable story of Jim Bouton, the journeyman Yankee who found himself in Nowheresville, USA in 1969, otherwise known as the clubhouse of the expansion Seattle Pilots. Bouton found gold in the Upper Northwest, producing the greatest sports book of all time: BALL FOUR. BOUTON not only shows not only how he did it but digs deeper and explores the life of a man who won all of 62 games but who changed professional sports in ways 300-game winners never could. To which Bouton's Seattle Pilot teammate, Jim Gosger, would most likely say, "Yeah surrre."

ICYMI:

After years of trying, Justin Turner has won the Roberto Clemente Award.

JT and five of his Dodgers teammates have been named as Silver Slugger finalists. These five: Mookie Betts, Freddie Freeman, Will Smith, Chris Taylor and Trea Turner. Find the full list of NL and AL nominees here.

Betts has won Gold Glove Award number six for his outstanding right field play. It’s his second as a National Leaguer after winning four in the in the American League. View the complete list of 2022 winners here.

Media Savvy:

Below are three stories from the Los Angeles Times, including two from one of my favorite baseball writers, Bill Shaikin, and one from another fine scribe, Jorge Casillo.

Mike Trout’s hometown team is in the World Series. Will he ever play for Phillies?

Rob Manfred: Oakland Athletics to Las Vegas isn’t imminent or guaranteed.

Here’s why Phillies star Bryce Harper turned down $45 million a year from Dodgers.

Here is ‘My eye over yours’: Ball-and-strike challenges, possibly coming to an MLB game near you,” by Zach Buchanan at the Athletic.

And finally, here is a 2019 article in which I asked three authors to pitch their new baseball books — the authors being Tyler Kepner, Danny Knobler and Tom Stone — at Forbes.

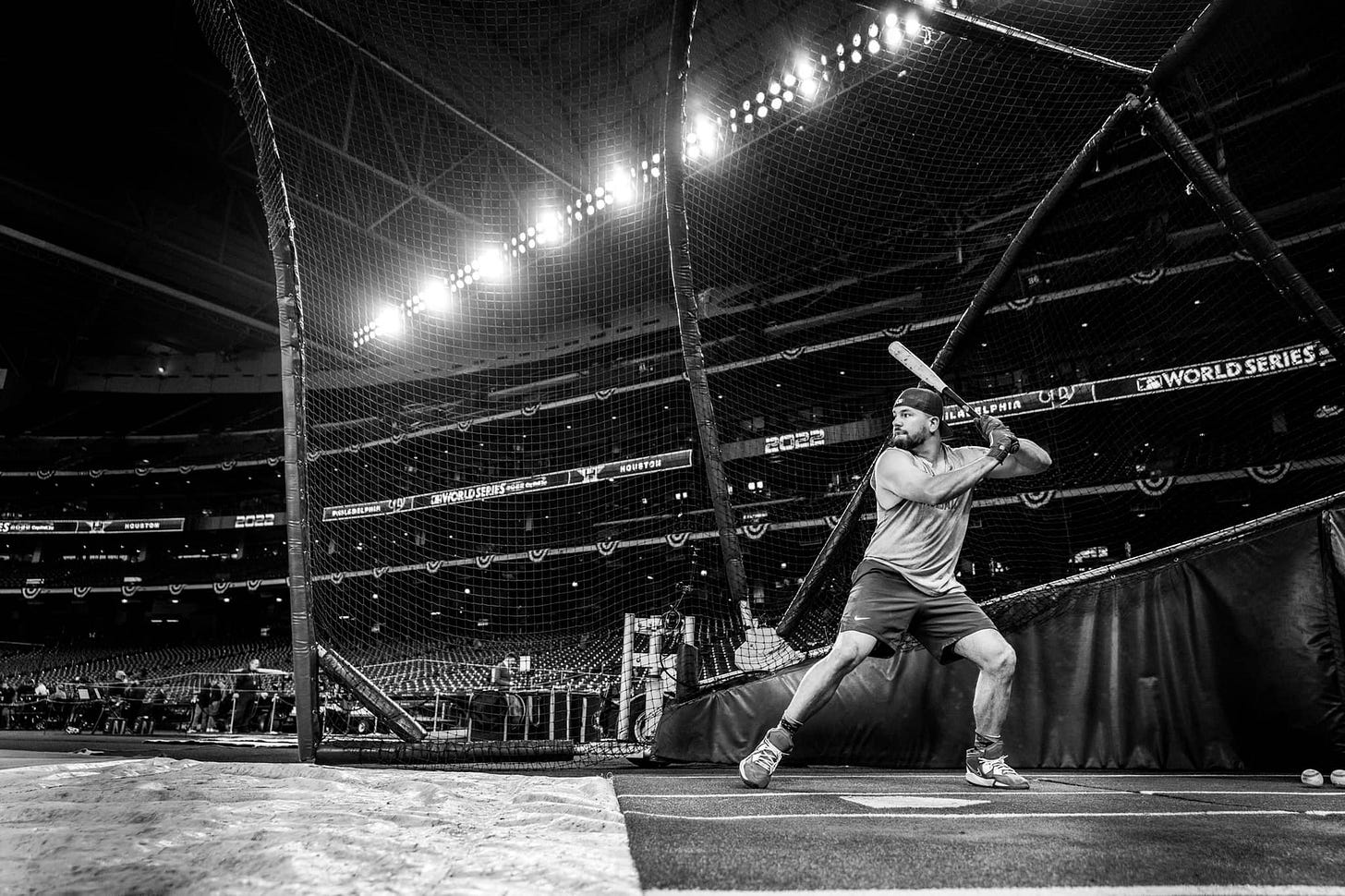

Baseball Photos of the Week:

Bryce Harper’s first inning, two-run homer gives the Phils a 2-0 lead in Game 3 Tuesday. Photo by David J. Phillip, Associated Press.

The Citizens Bank Park crowd, Game 3. Photo by Jean Furth.

Dusty Baker. Photo by Daniel Shirey, Getty Images.

“Dave Dombrowski has been working in M.L.B. front offices since 1978. As a president of baseball operations, he has led four different franchises to the World Series.” Photo by Lynne Sladky, Associated Press.

“Framber Valdez was checked for foreign substances throughout the game, just as all pitchers have been since last season.” Sean M. Haffey/Getty Images.

Nuns on the run. Uh, rooting for runs. Photo by Jean Furth.

Kyle Schwarber. Photo by Jean Furth.

J.T. Realmuto’s tenth inning home run gives Philadelphia the 6-5 win in Game 1. Photo by Annie Mulligan for The New York Times.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.