I’ve had an appreciation for Jim Gilliam’s accomplishments as a Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodger for as long as I can remember. Fifty years of listening to Vin Scully can have that type of effect on a person. As you know.

I’ve known that “Junior” was a member of L.A.’s 1965 switch-hitting infield — Wes Parker at first base, Jim Lefebvre at second, Maury Wills at shortstop and Gilliam at third — essentially forever. I knew that he was the 1953 National League Rookie of Year Award winner, and that his debut preceded Walter Alston’s. Or as Vin said many times, Gilliam was “the longest-serving Dodger,” until his untimely death during the 1978 National League Championship Series. I knew that Los Angeles retired his uniform number 19 two days later, on October 10, 1978, and that his is the team’s only retired number that did not belong to a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. I think for good reason.

With a glance at the now 25-year-old Baseball Reference website, I can tell you that Gillian played his age-17, 18 and 19 seasons with the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League II. Importantly, I can tell you that he is among the Dodgers franchise leaders in all manner of batting categories. For example, he ranks eighth in WAR position players (40.8), eighth in offensive WAR (37.7), fifth in games (1956), fifth in at bats (7119), third in plate appearances (8322), fourth in runs (1163), eighth in hits (1889), ninth in total base (2530), seventh in doubles (304), second in walks (1036), sixth in singles (1449), sixth in runs created (984) and third in times on base (2958).

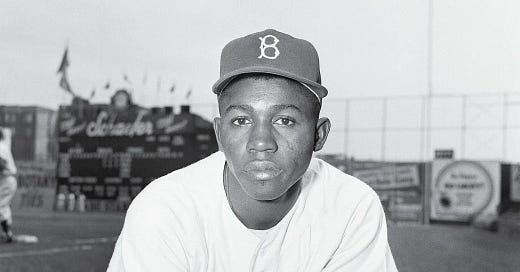

Most importantly, I can recommend a fine new book about this particular Dodgers great. It is “Jim Gilliam: The Forgotten Dodger,” by Steven W. Dittmore (August Publications, February 4, 2025, Paperback $24.95, Kindle ($9.99). The section I have chosen to excerpt here is the entire Chapter 12: From Bench To MVP Candidate, which begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 12: BENCH TO MVP CANDIDATE

LESS THAN TWO MONTHS AFTER THE DODGERS’ NINTH-INNING IMPLOSION IN the decisive 1962 playoff game, Buzzie Bavasi packaged infielders Larry Burright and Tim Harkness in a trade with the New York Mets for pitcher Bob Miller. The November 30, 1962 deal was designed to bolster the Dodgers relief corps, but it also allowed the team to move on from 1962. Burright, who was front and center in the Dodgers’ collapse in Game Three of the 1962 playoff, had started the 69 games at second base that Gilliam did not, but was deemed expendable as the Dodgers, of course, had another youngster waiting to force his way into the starting lineup.

Signed by Los Angeles in 1959 at the age of 18, Nate Oliver’s path to the Dodgers in spring 1963 bore a striking resemblance to the one Gilliam journeyed down a decade earlier. Like Gilliam, Oliver came from a baseball lineage. His father, James “Jim” F. Oliver, played for the Cincinnati Clowns of the Negro Leagues from 1941 to 1942, and also the Birmingham Black Barons in 1945, ending his professional baseball career the year before Gilliam began his. Nate’s older brother, also Jim, played baseball as well.

“Dad had had his fill,” Oliver recalled. “He wanted to spend time at home with us.”

Gilliam and Oliver possessed similar physical characteristics. The 1963 Dodgers yearbook listed Gilliam at 5-11, 180 pounds, while Oliver was 5-10 and 160 pounds. Just as Gilliam had his own diminutive nickname, “Junior,” so, too, did Oliver, who had somewhere along the way, acquired the moniker “Pee Wee.” Fifty years later, Oliver still did not know the origin of the nickname. “I have no idea. I think it had to do with my stature. I was 5-8, 150 pounds soaking wet,” Oliver said. “I’m not sure when or where it started, but it stuck.”

Oliver graduated from Gibbs High School in St. Petersburg, Florida. Opened in 1927, Gibbs High was Pinellas County’s first public secondary school for Blacks. White students began attending the school in the early 1970s after Florida integrated its public schools. Among its prominent alumni were former Major League infielders Ed Charles, the oldest member of the 1969 New York Mets, and George Smith of the Boston Red Sox, along with the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Steel Curtain standout safety Glen Edwards and Houston Oilers wide receiver Ernest Givins. Oliver’s father, Jim, was responsible for instructing and developing those players.

Today, Gibbs High sits in the heart of St. Petersburg, visible from the west side of Interstate 275, two miles from Tropicana Field, home of the Tampa Bay Rays. Across Interstate 175 to the south of Tropicana Field is Oliver Field at Campbell Park, named for Pee Wee’s father. Oliver Field was the first field to be refurbished under the Rays Field Renovations program in 2006.

As the Dodgers had done with so many of their Black players in the 1950s, including Gilliam, the team assigned Oliver to an integrated city in the North. In Oliver’s case, this meant the Class B Green Bay Bluejays and, later, the Fox Cities Foxes in nearby Appleton. Predictably, the young Oliver struggled being so far away from home. In 1960, however, he blossomed, batting .329 with 15 triples and 30 stolen bases for the Class C Great Falls Electrics, even earning a brief promotion to Triple-A St. Paul. Oliver was on the fast track from there, batting .266 for Triple-A Spokane in 1961, where his teammate was 35-year-old Don Newcombe, trying to get back to the Major Leagues after his release from the Cleveland Indians in January 1961.

At the age of 21, Oliver hit .317 for Spokane in 1962, playing second base alongside future Dodger teammates Dick Nen at first base, Dick Tracewski at shortstop, and John Werhas at third base. Just as Gilliam had done 10 years earlier, Oliver would spend that winter honing his craft in Puerto Rico, forcing the Dodgers to find a place for him in the big-league lineup.

As was the norm in baseball in the early 1960s, the Dodgers had two Triple-A minor league affiliates. In addition to the Spokane Indians, managed by Preston Gomez, the Dodgers also had an agreement with the Omaha Dodgers, managed by Danny Ozark. By the 1965 season, both Gomez and Ozark would serve as coaches for Dodger manager Walt Alston. The 1962 Omaha club boasted another hot, young Dodger prospect in Ken McMullen, a native of Southern California. McMullen, who turned 19 midway through the 1961 season, tore up Class C Reno, batting .288 with 21 home runs, 109 runs scored, 96 RBI, and 107 walks while playing exclusively at third base. In Omaha in 1962, however, McMullen split time among third base, first base, and the outfield. He hit .282 with 21 home runs, good enough to earn a September call-up to the big league Dodgers, where he logged 11 at bats.

As the Dodgers sought to get younger, the 22-year-old Oliver certainly figured into the team’s plans going into Vero Beach in spring 1963. Bob Hunter noted in The Sporting News the Dodgers, even with 32-year-old Moose Skowron at first base instead of the 20-year-old McMullen and Oliver at second, could field a starting nine with an average age of 26.

Predictably, Hunter’s hypothesized lineup did not include Gilliam. Finding himself once again without a position heading into spring training, 34-year-old Jim Gilliam’s future with the club looked cloudier than ever, despite his solid 1962 season.

“Every year there’s been some pheenom (sic), repeat pheenom, who was gonna take his job. None of them has yet. It never shakes him up. Gilliam brings three gloves and waits around and says, ‘Well, I’m gonna play some place.’ So you’d play the pheenom all spring and Gilliam would get in 152 games anyway,” Dodger manager Walter Alston told Jack Mann for Sport magazine in its January 1963 issue.

Alston’s quote resonated so much with the Sport magazine editors, they titled the article, “Gilliam Brings Three Gloves and Waits Around.” The article’s author, Mann, was a national sportswriter specializing in baseball, serving as sports editor at Newsday and would eventually write for Sports Illustrated from 1965-67. He was effusive in his assessment of Gilliam’s abilities, and inabilities, calling him “the finest mediocre ballplayer who ever walked…and walked….and walked. There will be no votes (except one) for Gilliam’s admission to the Hall of Fame. He has been a great player, not because of the talents he has but in spite of the talents he hasn’t.”

In 1953, Gilliam moved Jackie Robinson from second base to third base and sent Billy Cox to the bench. Charlie Neal moved Gilliam to left field in 1956, and later to third base in 1959. Now, in 1963 after Gilliam had reclaimed second base, Oliver and McMullen were forcing the same domino effect. Their presence, along with that of Tommy Davis, created a surplus of options for Gilliam’s primary positions: second base, third base, and left field. Gilliam was, once again, without a home, wrote Hunter in The Sporting News. “While Gilliam has no job, it’s the same old story for him. He never has a job—until the day the season opens, then he’s in there some place.”

As training camp wore on, the possibility of an opening increased as the experiment with Davis at third base failed. A sore arm contributed to eight spring-training errors, most on errant throws, forcing Alston to reevaluate his options. He would turn first to McMullen as a potential starter at third, knowing veterans like Gilliam, Daryl Spencer, and Don Zimmer (reacquired via trade with the Cincinnati Reds in January), still existed on the roster, as did the slick-fielding, 28-year-old Dick Tracewski.

With one week to go before Opening Day in Chicago on April 9, Alston was still unsettled as to who would play third, but Oliver was now entrenched at second base. Not only had he taken Gilliam’s defensive spot, but Oliver now occupied Junior’s spot in the batting order. “Pee Wee still has to prove he can hit big league pitching seven days a week, but if we opened today he would be my No. 2 hitter,” Alston told the media on April 2.

Alston authored a bylined scouting report on his Dodgers on Monday, April 8, the day before the season began. Whether he wrote it or it was ghost-written is up for debate, as the language reads more like a sports writer than a manager. In the article, Alston expressed cautious optimism for Oliver at second, “Oliver seems to have what it takes—savvy, good hands, plenty of range and good wrist action at the plate. Whether he can be a capable No. 2 man in the batting order, behind leadoff man Maury Wills, remains to be seen. That’s a tough assignment because Jim Gilliam was one of the best.”

Similarly, Alston was uncertain about third base, where he iterated confidence in McMullen, but acknowledged the presence of Gilliam, Spencer, and Zimmer. “It would be nice to have the job settled, but we may have to wait a bit before we say, ‘That’s it.’” Alston wrote.

The manager could not have scripted the opening inning of the opening game of the 1963 season any better. Wills opened the top of the first at Wrigley Field with an infield single off Cubs starter Larry Jackson. Oliver worked the count to 3-1 before stroking a single to right, sending Wills to third where, one out later, he would score on a ground out. Oliver, playing the role of Jim Gilliam by batting second and playing second base, had recorded his first major-league hit in his first major-league at bat. Oliver collected two hits on the day and McMullen contributed a two-run double in the top of the ninth, adding insurance to a 5-1 victory for starting pitcher Don Drysdale.

Through the season’s first nine games, Gilliam was relegated to pinch hitting duties with an occasional appearance at third base late in the game. Finally, in the season’s tenth game on April 19, Gilliam was in the starting lineup, batting second and playing third base. Gilliam led off the bottom of the seventh against Houston’s Turk Farrell with a double, his first hit of the season, and scored two batters later when Frank Howard homered. The Dodgers won, 2-0, behind Sandy Koufax’s two-hit shutout. It was Gilliam’s 1,500th career game played.

THE BUS INCIDENT

The Opening Day success notwithstanding, the entire Dodger team seemed to struggle to begin 1963. Oliver started the first 22 games at second, but after his sparkling debut, his bat cooled. An 0-for-9 stretch had dropped his average to .218, and he had struck out five straight times.

Playing sparingly, Gilliam was batting just .167 when he made his first start of the season at second in Pittsburgh on May 3. At the same time, Alston moved Tommy Davis to third base, replacing the combination of McMullen (who was sent to Spokane on May 8 with a .205 average), veteran Spencer (released on May 10), and Gilliam.

Following a 7-4 loss at Pittsburgh on May 6, the Dodgers’ record stood at 12-14. Los Angeles held a 4-2 lead headed to the bottom of the sixth in that game when things went sideways. Ted Savage opened the inning with a ground ball to Gilliam, whose wild throw from his second-base position allowed Savage to reach safely in front of Pirates sluggers Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente. The Pirates would score four runs in the inning, three of them unearned because of Gilliam’s miscue.

The club was now in eighth place, ahead of only the New York Mets and expansion Houston Colt .45s, and tempers on the club were beginning to flare. According to the Los Angeles Times’ Frank Finch, Alston had “built up a head of steam and blew his lid” as the team rode a bus to the Pitts burgh airport where they would fly to St. Louis. Players were reportedly complaining “vociferously” about cramped conditions and lack of air conditioning on the bus. Some began yelling at traveling secretary Lee Scott, who responded, “If you guys would win some games, instead of kicking ‘em away, you might deserve an air-conditioned bus.”

Alston, seated in the front seat, instructed the bus driver to pull over to the side. Alston stood up and first chided Scott for his comments about losing, and then offered to cede bus procurement to any of the players. “Can everybody in the back hear me?” Alston asked. “Ok, I’ve heard enough wrangling about what kind of busses we use. Does anybody want to volunteer to check the bus we get in St. Louis?” There was silence.

Alston was just beginning. “I kept getting angrier—and hotter,” he wrote. “I said if nobody liked the new arrangements we could handle the complaint any way they liked—by talking it out privately, or in front of everybody, or if they weren’t satisfied right now, I’d be glad to step out on the sidewalk and have it out. I concluded by emphasizing, ‘What I’ve just said goes for everybody.’”

No one took Alston up on his offer to handle bus procurement, nor to discuss the matter further. While the speech was prompted by a literal bus, the metaphor for getting the team on the right bus seemed appropriate. Writers noted the “Bus Incident,” as Alston called it, was the turning point of the season. Even though things would immediately improve for the Dodgers, Alston wrote, “it was strictly coincidental.”

The Los Angeles Times reported the bus awaiting the Dodgers in St. Louis was air conditioned. Coincidental or not, the Dodgers jumped on the Cardinals the next day, May 7, scoring nine runs in the first four innings en route to an 11-1 win behind a strong start from Koufax.

Around the same time, Alston switched the lineup again, starting Tracewski at short and shifting Wills to third, with Gilliam now ensconced at second. “A lot of the guys on the team, and Jim Gilliam in particular, wanted me to play shortstop and move Maury to third base,” Tracewski said years later. “It actually happened for a while and I was playing fairly good as I remember. One day I came back into the clubhouse and looked at the lineup that was posted and Maury was back at shortstop.”

That day was June 29 when Wills resumed his role at short, McMullen starting at third, and Gilliam at second. The lineup tinkering continued the rest of the season, with Lee Walls and Marv Breeding also getting shots in the infield.

Following The Bus Incident, Gilliam went on an offensive tear, collecting five hits in 12 trips in St. Louis, including his first home run of the season. He did not know this at the time, but Gilliam was in the midst of a 15-game hitting streak, the second longest of his career. His consecutive games streak of reaching base safely hit 30, the fourth longest of his career.

When May ended, Jim had hit in 22 of 25 games played during the month, raising his average from .167 to .297. He batted .348 (32 hits in 92 at bats) with 11 walks and 18 runs scored. Midway through the streak, though, Gilliam commented, “I can’t remember what my longest hitting streak was. What you did last year and the year before that you can forget. This is another season.”

More important than Gilliam’s individual accomplishments was the team’s turnaround with him entrenched in the lineup. The Dodgers vaulted from eighth place before The Bus Incident, to third place, just two and-a-half games behind San Francisco on May 31.

On the season, Alston would use seven different starting third baseman and four different starting second baseman. Gilliam made 110 starts at second and 27 more at third. Alston would also run seven different players out in left field. Los Angeles used 21 different position players in 1963, an unusually high number for that era, necessitated by player injuries, slumps, and transactions.

“There was criticism of the manager from time to time because of his ‘refusal’ to stick with a set lineup. I was accused of carrying platooning to extremes. My only answer was that if it took a lot of players to win, that’s how it had to be. Nobody would have enjoyed playing a regular eight more than the skipper of the Dodgers if he could have found enough consistency in his crew,” Alston wrote years later.

Tracewski was one of those players moved around by Alston, until the end of the season. After starting 24 games at shortstop in June, Tracewski started 16 games the rest of the season, with five of those starts at second base, not his normal position. When Alston started Gilliam at third, Wills at short, and Tracewski at second on the last day of the season, September 29, it was only the second time all year the triumvirate had played the infield together. One week later, they played every inning together and were World Series champions.

NO-HITTER #5

Ladies’ Night at Dodger Stadium was held May 11, with Los Angeles Times writer Frank Finch predicting “plenty of dolls will be on-hand for the hurling heart throb, Sandy Koufax.” Koufax would be opposed by Giants star Juan Marichal. During their 1960s rivalry, Gilliam logged 96 plate appearances against Marichal with little success, hitting just .224 with 10 walks. Marichal struck out Gilliam nine times in their career, about one out of every 11 confrontations. Over the course of his career, Gilliam struck out only 416 times in 8,322 plate appearances, a ratio of once every 20 trips to the plate. Marichal definitely gave Gilliam problems.

On this night, however, in front of more than 55,000 spectators, Marichal struggled once the game reached the sixth inning. A Wally Moon home run to open the second had given Koufax a 1-0 lead. That score held until the bottom of the sixth, when Gilliam laced a line-drive single to right, his second hit of the game off Marichal. One out later, Tommy Davis singled Gilliam to second. Moon followed with a line-drive single to right fielder Felipe Alou, scoring Gilliam. After an intentional walk to Ron Fairly loaded the bases, Roseboro singled in two more runs. A fifth single in the inning, this time an infield hit from Tracewski, chased Marichal. The Dodgers now led 4-0.

With a comfortable lead, Alston decided to go to his bench in the top of the seventh, earlier than normal. Just as he had done the night before, Gilliam moved from second to third, with Tommy Davis replacing Moon in left, and Oliver inserted at second. Koufax had retired all 18 Giant batters he had faced. He was nine outs away from a perfect game.

After retiring Harvey Kuenn on a fly ball to right to open the seventh, Felipe Alou’s blast to left was caught by Tommy Davis with his back against the bleachers. Willie Mays then “slugged a screamer which Jim Gilliam speared on the fly at third base.” Melvin Durslag of the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner described it as a “blistering liner which Jim Gilliam stabbed behind the third base bag.” Sportswriters believed Gilliam’s defensive play was one of the game’s key moments. It would not be the last time in his career that Gilliam would boost Koufax with his defense.

Six outs to a perfect game. Orlando Cepeda led off the eighth for the Giants. With a 1-0 count, Cepeda hit a sharp grounder back up the middle, deflecting off Koufax’s glove right at Oliver, who threw to first for the out. Five outs to go.

Nearly 60 years later, Oliver recalled not feeling nervous as the ball caromed to him. “The adrenaline flow during a no-hitter is unbelievable. You can’t wait for the ball to be hit to you,” Oliver said. “We would say, ‘if the ball comes this way, the guy is going to make a right turn.’”

Koufax lost the perfect game when the next batter, Ed Bailey, worked a walk on a full count. Koufax would go full on Jim Davenport before getting him to bounce to a Tracewski-Oliver-Fairly double play. Koufax still had the no-hitter, facing the minimum number of batters. The Dodgers padded their lead in the bottom of the eighth when, with two outs and Gilliam batting, pitcher John Pregenzer balked home Tracewski. Gilliam worked a walk to load the bases. All three runners scored on Fairly’s double to right, giving Los Angeles an 8-0 lead and one question. Would Koufax get the no-hitter?

Joey Amalfitano and Jose Pagan each flew out to open the ninth, when Willie McCovey strode to the plate to bat for the pitcher. Koufax threw four straight balls to issue his second walk of the game. Kuenn hit a bouncer back toward Koufax, who fielded it, ran toward first, and care fully lobbed the ball to Fairly for the final out. Koufax had his second career no-hitter. For Gilliam, it was the fifth time in his career in which he had participated in a no-hitter.

THE NEGRO PROBLEM

Just as the Dodgers began rolling in the summer of 1963, a Jet magazine cover story in June revisited a topic covered back in 1954, regarding how many Black players in a lineup was too many. Titled “Do the Dodgers have a Negro problem?” the magazine cover featured photos of six Black Dodger regulars: Maury Wills, Willie Davis, Tommy Davis, John Roseboro, Nate Oliver, and Jim Gilliam. The article, authored by longtime Black sportswriter Andrew S. “Doc” Young, was a response to an article written by syndicated New York Post columnist Milton Gross a month earlier. Nearly 10 years earlier, in March 1953 Gross had authored an article, “The Inside Story of Trouble on the Dodgers,” initiating conversations about race after Gilliam was named starting second baseman, relegating white infielder Billy Cox to the bench.

In 1963, Gross quoted an unnamed white Dodger player as saying the Dodgers do not field their best lineup because six of the players would be Black. “Are you nuts?” the player responded to Gross’s inquiry. “The front office doesn’t want to have six out of eight colored players starting a game.” Dodger general manager Buzzie Bavasi, clearly no fan of Gross, told Young in Jet magazine, “I consider the source it comes from. I know Milt Gross. He’s doing it to attract readers and doesn’t care whom he hurts….If we had eight Jackie Robinsons, we’d play all eight of them every day.”

Whether Bavasi was serious about playing eight Black players is unclear in part because no team in the early 1960s was keeping extra Black players on their roster. It was the same situation as a decade earlier, when the Dodgers kept Gilliam in the minors for two years instead of having him on the bench as a utility player. The Black players teams kept were superstars, not bench players. Recalling those 1960s Dodger teams, Tommy Davis wrote, “There weren’t too many Black players who sat on the bench. Either you started or you went back down to the minors or moved on to another organization or went home.

“Think about it in terms of the Dodgers back then. Maury Wills and Jim Gilliam were both really important parts of that team. Willie Davis played. I played. Roseboro played. Who’s sittin on the bench who’s Black? No one.”

Los Angeles did have a few Black bench players at different times during the 1960s. Infielder Nate Oliver averaged 60-plus games played between 1963 and 1967. The addition of Lou Johnson in 1965 after Tommy Davis suffered a season-ending injury created an extra Black outfielder in 1966. The team also added 34-year-old journeyman outfielder Wes Covington in 1966, but Covington batted just .121 in limited action on his last stop in the majors. Teenage outfielder Willie Crawford logged 51 plate appearances between 1964 and 1967 and even recorded a hit in the 1965 World Series as an 18-year-old.

Outside of those four players, Tommy Davis’ comments were accurate. Black players on the Dodgers during this period were either starters or minor leaguers.

KILLER INSTINCTS

By late July 1963 the Dodgers had built a comfortable lead over second place St. Louis and were in Milwaukee to play the Braves. Koufax started for Los Angeles, but was replaced in the sixth by Ron Perranoski. Now, with the Dodgers holding a slim 5-4 lead in the bottom of the ninth, seldom-used Braves outfielder Don Dillard was sent to first base to pinch run for Joe Torre. With two out, Mack Jones hit a grounder back to the mound, deflecting off Perranoski and carrying toward Maury Wills at short. With no chance to get Dillard, Wills rifled the ball toward first. Dillard’s path to second had taken him in the line of Wills’ throw and the ball hit Dillard above the right eye, knocking him out, short of the base.

The ball caromed back toward Wills. Gilliam, playing second that day, alertly called for the ball and tagged Dillard, who had staggered across second and was lying unconscious on the ground not touching the base, for the game’s final out.

“Everyone was worried he had been killed and went to him, except Gilliam, who was playing second. Gilliam was only worried about the out, and he went to the ball and tagged the unconscious player to make sure he was out,” John Roseboro wrote in his memoir. “‘That’s the first time I tagged out a dead man,’ chuckled The Devil.”

Dillard left the field on a stretcher and was taken to a local Milwaukee hospital for “repairs to his damaged features.” The Los Angeles Times reported he suffered no fractures and needed seven stitches to close the wound. Dillard missed the next week of action.

SEASON STATS: A MODEL OF CONSISTENCY

The 34-year-old Gilliam finished the season with a .282 average, the third time in his career he would hit exactly .282. Though not a stat at the time, his 5.2 wins above replacement would be the second highest in his career, behind a 6.1 WAR in 1956, and was second highest on the team, behind Koufax’s ridiculous 9.9 WAR. As had been foretold prior to the season, Gilliam had merely waited around and was presented a chance to play. He had withstood, for now, the challenges of “pheenoms” and eclipsed 600 plate appearance for the 10th time in his career.

Jim’s season splits showed how steady his season was: a .281 average in the season’s first half and a .283 average in the second half. His home and away splits, .288 and .277, were also basically equal. He excelled against the league’s top contenders, batting .312 against the runner-up Cardinals and .319 against the third-place Giants.

1963 WORLD SERIES: THE YANKEES AGAIN

Los Angeles found itself playing a familiar foe in the 1963 Series: the New York Yankees, who sported a 104-57 record, finishing 10.5 games ahead of the Chicago White Sox. New York entered the Series as the two-time defending World Series champions and in the middle of appearing in four straight Fall Classics.

New York boasted a potent lineup of sluggers, including Elston Howard, Joe Pepitone, Tom Tresh, Roger Maris, and Mickey Mantle, who missed 61 games due to a broken foot. On the mound, the Yankees were led by Whitey Ford and a rookie left-handed pitcher and future Dodger, Al Downing.

“We should have won in ‘62. We were the best team in ‘62. But we didn’t win,” Dick Tracewski said. “In ‘63 our club was so focused it was unbelievable. When we went over the Yankees, they had Maris, Mantle, (AL MVP) Elston Howard…and Pepitone. They just had a complete nine guys who were All-Stars.”

Two legendary lefties, Sandy Koufax and Whitey Ford, were matched in Game One at Yankee Stadium on October 2. Los Angeles plated four runs in the second inning, punctuated by a three-run home run by John Roseboro, and won the game, 5-2.

Game Two of the World Series also featured two lefties, the Yankees’ Al Downing against the Dodgers’ Johnny Podres, the next day in the Bronx. Los Angeles struck swiftly in the first when Wills opened with a grounder through the mound, which Downing, more than 50 years later, contended he should have fielded, “The ball just stayed down.” Downing figured he had an advantage on Wills—who had never seen his pickoff move—and, on Wills’ first move, Downing fired to first baseman Joe Pepitone. The subsequent throw to second base was too late; Wills had stolen second. Downing now turned his attention to Gilliam at the plate.

“Jim was hard to pitch to. He understood what his job was. Whatever the situation called for, he would do. That was the mark of a solid ballplayer,” Downing said. In this instance, Gilliam’s job was to get Wills to third, which he executed perfectly by singling to right field, where Roger Maris fielded the ball and threw home. But Wills held at third and Gilliam, always thinking, took second on the throw. Willie Davis followed with a double to right over Maris’ head, and three batters into Game Two, Los Angeles already led, 2-0. The Dodgers won the game, 4-1, sending the Series to Los Angeles with a 2-0 advantage.

In Game Three, the Dodgers again drew first blood, scoring a run in the bottom of the first. After a Wills ground out, Gilliam worked a walk against starting pitcher Jim Bouton. An out later, Gilliam took second on a wild pitch. He scored when Tommy Davis bounced a bad-hop single between second and short. The lone run was all Don Drysdale needed for Los Angeles. Drysdale limited the Yankees to five base runners and struck out nine en route to the 1-0 victory. The Dodgers were one game away from a four-game sweep of their nemesis.

Game Four took place on October 6, a sun-splashed Sunday afternoon featuring a rematch of Game One’s starting pitchers, Ford and Koufax. Frank Howard smacked a solo homer in the fifth for Los Angeles, but Mickey Mantle’s home run in the top of the seventh tied the game at one apiece, setting the stage for more heads-up base running from Gilliam. Just 2-for-12 in the Series, Jim hit a Ford pitch that took a high bounce to third baseman Clete Boyer, whose throw to first was perfect except for one thing: Joe Pepitone, the first baseman, lost the white ball in the bright sunlight and white short-sleeve shirts from the crowd. The ball, free of any leather glove, took off down the right-field line. Gilliam alertly raced to third. Willie Davis hit a sacrifice fly on the next pitch, scoring Gilliam with the go-ahead run. Los Angeles now led 2-1.

Koufax held the Yankees off in the final two innings as the Dodgers swept the Series, four games to none. Los Angeles’s pitching dominated, limiting the Yankees to a .171 batting average and .207 on-base percentage. The Dodgers used only four pitchers in the Series, as Koufax threw two complete games while Don Drysdale threw another. Ron Perranoski relieved Johnny Podres in the ninth inning of Game Two. Defensively, the Dodger infield was static, with Moose Skowron at first, Tracewski at second, Wills at short, and Gilliam at third. Eleven of the 25 Dodgers on the roster did not play in the Series. “We were very good defensively and we could pitch like hell,” Tracewski said. “We caught them when they weren’t hitting and that happens a lot.”

The Dodgers’ World Series triumph netted Gilliam, and his teammates who received a full share, a $12,974 bonus.

A SURPRISING 1963 MVP VOTE

Twenty members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America cast ballots for each league’s respective Most Valuable Player. When the results were released on October 30, half of them had Gilliam’s name on their ballot, placing him sixth in the league vote, behind winner Koufax, Cardinals shortstop Dick Groat, Braves outfielder Hank Aaron, Dodgers reliever Ron Perranoski, and Giants outfielder Willie Mays. First-place votes were divided among Koufax (14), Groat (4), Aaron (1), and Gilliam (1). One writer omitted Koufax’s name on his ballot altogether. Dodger outfielder Tommy Davis placed eighth in the final tally, giving Los Angeles four of the top eight vote earners. Koufax would also win the league’s Cy Young Award, joining teammate Don Newcombe, 1956, as one of first pitchers to have won both awards in the same year.

Bob Hunter, a long-time sportswriter for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner and The Sporting News, acknowledged he was the one vote for Gilliam. “That one vote was mine,” Hunter wrote in The Sporting News on January 11, 1964. “Yes, I’m of the old school that would separate the pitchers from the regulars and Sandy Koufax was a shoo-in for the Cy Young Award. As it turned out, he swept them both.”

Speaking to Sid Ziff of the Los Angeles Times, Koufax stated, “I am amazed Junior didn’t finish higher. Gilliam never gets what he deserves. He deserved to be higher.” In typical fashion, Jim deflected his teammate’s praise. “That was nice of (Koufax), but I doubt if I deserved more. I am pleased as it is.”

Ziff called Gilliam’s 1963 season “perhaps his finest,” noting that “every spring for the past three or four years they’ve been expecting some kid to chase him out of a job.” Gilliam, who had turned 35 in October, responded to Ziff, “Some day that young fellow won’t be back to the farm. I know I can’t go on forever, nobody can. And the Dodgers can’t afford to stand pat. They want to stay up there for years. They got to bring in the kids. I realize that.”

Former Yankee first baseman Bill Skowron, who joined the Dodgers for the 1963 season and won his fifth World Series, paid Gilliam the highest compliment after the season. “For years, I’ve known Jim was a pro, but I didn’t really appreciate his value until I got to play alongside him.”

Gilliam’s age continued to be a hot topic entering the offseason. “I don’t know how old he is,” Alston claimed. “But that never enters my mind. You can count the mistakes he’s made in his major league career on your fingers.”

Despite his sixth-place finish in the MVP race, national sports writers were already dismissing Gilliam’s productive season. The Dodgers’ “infield, where Jim Gilliam alternated at second and third base with Dick Tracewski (2b) and Ken McMullen (3b), could stand bolstering,” wrote Herbert Simons in the December 1963 Baseball Digest. Even Hunter acknowledged the person he voted for as MVP in 1963 might not have a job in 1964. “Gilliam’s work in the championship drive was recognized by enough votes to give him sixth place among the N.L. stars, but still the 35-year-old pro doesn’t know whether he will be playing second or third or as a utilityman. It was the same last spring and the spring before and the spring before that.”

About the author:

Steven W. Dittmore has more than 20 years of experience working as a higher education administrator and professor. Dittmore received a PhD from the University of Louisville in 2007 and holds bachelor's and master’s degrees in journalism from Drake University. He is an assistant editor at AthleticDirectorU, a vertical website from D1.Ticker designed to promote thought leadership ideas among intercollegiate athletic directors, and also writes for his Substack newsletter, “Glory Days.” A recognized researcher in the areas of sport media and intercollegiate athletics, he is a co-author of a Sport Public Relations textbook and is preparing revisions for a fourth edition. He is an author on nearly 50 peer reviewed journal articles, 12 book chapters, and more than 70 peer reviewed presentations.

Born in Southern California, he is a lifelong fan of Dodgers baseball and enjoys studying the history of baseball as an active member of the Society for American Baseball Research. In August 2023, he was part of the 75th Anniversary Celebration of the 1948 Cleveland Indians World Series championship, presenting a historical perspective of Dale Mitchell, an Indians outfielder inducted into the team's Hall of Fame that evening.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the internet since Y2K. Follow him on Bluesky. And Twitter. Read OBHC online here.

Junior Gilliam was one of the best to ever put on a Dodger uniform. So glad I was alive and watching (by 1962) fairly soon after the Dodgers entered the Southern California sports scene.

Great stuff. Thanks, Howard.