Book Excerpt: Last Time Out: Big-League Farewells of Baseball’s Greats

Chapter 45: Ted Williams 1960.

The hits just keep on comin’. Hits in a player’s final at bat in a book chock full of them, for one thing.

“Let’s see: Joe DiMaggio got a double, Reggie Jackson, George Brett got singles, Stan Musial had a two-hit game (to get to 1,815 home and away - 3,630), Joe Jackson got a game-winning double for the one pitcher who had been TRYING to win in the 1919 World Series, Dickey Kerr. Joe Morgan got a double, Aaron an infield hit (to deep short), Jeter an infield hit (on a weird bouncer to third), Clemente of course, got a double for his 3,000th hit...(but Pirates lost in the playoffs)... I think that's it,” say’s the author.

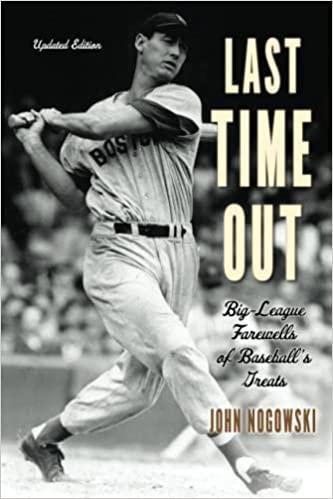

The hits keep coming to our celebration of baseball books too. With number 18 in the excerpt series, I am happy to recommend yet another fascinating work. It is “Last Time Out: Big-League Farewells of Baseball’s Greats,” by John Nogowski (Tayor Trade Publishing, originally published in 2005 and updated in 2022, Kindle $16.49, Paperback $17.59).

There are 45 player chapters in the latest edition, beginning with Babe Ruth and ending with the author’s son, John Nogowski, Jr., who made 147 plate appearances for the Cards and Pirates in 2021 and 2022 with an overlapping eight-year minor-league career. Pitchers’ final outings are included as well, all of them great reads. Because both of the Dodgers featured in “Last Time Out” ended their careers in World Series defeat — Jackie Robinson in 1956 and Sandy Koufax in 1966 — I wasn’t going to go there here. Buy the book and cry on the pages yourself. You’ll just have to make do with a detailed look at the Ted Williams chapter instead, which follows below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 25: Ted Williams

Perfect Swing, Perfect Finish (1960)

September 28, 1960

SITE: Fenway Park, Boston, Massachusetts

PITCHER: Jack Fisher of the Baltimore Orioles

RESULT: Home run into the right field bullpen

Okay, so maybe he wouldn’t go out with a home run. That stubborn realization seemed to sink in slowly in the most stubborn of men as he walked out of the Boston Red Sox dugout and kneeled down in the on-deck circle. It was the eighth inning of a cool and overcast Wednesday afternoon in late September. This was it.

The Baltimore Orioles were in town and, after a good run at the New York Yankees, they’d fallen a little short in their pennant run. Like Boston, they were just playing out the schedule. After a walk and two long flyouts on this dank, damp day, it didn’t look like Ted Williams, Boston’s famed slugger, was going to go out the way he wanted to, the way he’d been planning to, with a home run.

He knew this kid Fisher, Jack Fisher, a right-hander with a good fastball, was going to go right after him, just like he did in his two previous at-bats. Hard stuff against the old man. He had thought he caught that last one in the fifth just right. The ball jumped off his bat and the fans rose to their feet. There was something about the sound of Ted Williams hitting one.

But the long, majestic flyball backed Orioles center fielder Al Pilarcik right to the 380 sign on the green wall of the bullpen in right-center in Fenway Park. Then he caught it.

When Williams got back to the dugout, he saw Vic Wertz, who knew a little bit about being robbed by a center fielder—Wertz’s everlasting moment of glory came when Willie Mays had robbed him in the World Series six years earlier—and shrugged.

“Damn, I hit the living hell out of that one,” Williams said. “I really stung it. If that one didn’t go out, nothing is going out today.” Yeah, all these young pitchers were going at ol’ Ted now, like you’d expect young pitchers would against a tired 42-year-old. Last week in Washington Chuck Stobbs had struck him out twice with men in scoring position.

Ted had the last laugh there. The next night, Pedro Ramos tried the same thing and Ted got his revenge with a two-run shot over the right field wall. It won the ballgame.

That was his 28th home run of the season, the 520th of his career, putting him third on the all-time list at that time behind Babe Ruth (714) and Jimmie Foxx (534).

Here he was, down to his last at-bat and it looked like he was going out on 520. This last week hadn’t been much fun. Tuesday night in Baltimore, Williams fouled a ball off his ankle in the first inning and had to leave the game. He caught a plane back to Logan Wednesday afternoon where he was met by the local press. Williams shrugged it off.

“You might think this was a broken leg with all this fuss,” Williams told the media. “I expect to finish the season playing. There is no reason why I shouldn’t.”

He didn’t get back into the lineup until the Yankees came into Fenway on the weekend and swept the Sox to clinch the pennant. Williams was still swinging the bat pretty well. On Friday night he had a double off Bob Turley. On Saturday, he had three hits against an assortment of Yankee pitchers. On Sunday, he had two hits off Ralph Terry.

But Williams had gone hitless in two trips in the previous day’s embarrassing 17–3 loss to the Orioles. That was a reason to get out. Enough of those kinds of ballgames. His average? Well, he was still over .300. About .316. Not bad for 42 years old.

The afternoon crowd was pretty sparse, considering Williams was New England’s most notorious—if not necessarily loved—professional athlete. There wasn’t a lot of fanfare over his final game in Boston. Only a middling crowd of 10,454 showed up (even tiny Fenway can hold three times that), and there wasn’t any big hullabaloo from the national media. It sounded like the Red Sox feared that might happen with a controversial star like Williams.

Williams broke the news that he was quitting on Sunday after the Yankees had clinched their 25th pennant by sweeping the Red Sox. You can bet Ted laughed when he read the front-page story in Monday’s Boston Globe, a story that was played above the bold headline “Strike Vote Threatens to Idle All G.E. Plants.” It read simply: “Ted Quits—as Player.”

“It is the hope of the Boston management that Fenway Park will be filled on Wednesday to bid farewell to Ted,” Globe writer Hy Hurwitz wrote. Fat chance of that, Williams laughed. These Red Sox didn’t draw. There was no TV coverage, local or national, and none of the major papers had sent their columnists out to see Teddy’s bye bye.

One reason was the Red Sox were a lousy team and they’d been out of the pennant race for some time. Another was the team was going on to New York to close out the regular season. Maybe some expected Williams would wrap it up there.

Or it could be they didn’t see it as a big deal. Nobody saw it as an event. Athletes retire all the time, usually with a whimper. Who’d want to see Ted Williams go out with a whimper? Williams had retired before—or so he had announced—five years earlier, taking $10,000 to write a magazine series for the Saturday Evening Post, “This Is My Last Year in Baseball.”

He was heading into a divorce and ultimately didn’t join the team until mid-May because of all the squabbling. But he could still hit. He hit .345 in 1956 and would have won the batting title if he’d had the necessary number of at-bats. The next year, 1957, he hit an amazing .388. So he played a little longer.

Now, though, this was the end of the line. The pennant race had already been decided —Williams sat in the dugout that Sunday afternoon knowing with another win, the Yankees had run off nine straight—including a sweep at Fenway—to clinch one more pennant.

He watched Yankees reliever Luis Arroyo come in and get Boston’s Pete Runnels, the AL batting champion, to foul out to third with the game-tying run right there. That was the Red Sox for you. Close but no cigar.

With the pennant race officially over, Williams had given Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey the okay in the clubhouse to announce to the newspapers that he’d be retiring at the end of the season. The Red Sox said Williams would go to spring training as a batting instructor. Some thought he’d be Boston’s new general manager.

During Wednesday’s game, it had been announced in the press box during the game that Williams’s number 9 would be retired after the game. That drew a few cracks from the peanut gallery about Williams playing in his undershirt at Yankee Stadium.

The official pronouncement that he wasn’t going to New York hadn’t been made yet, except to a few people in the Red Sox clubhouse. Williams had already given the word to manager Mike Higgins that he wasn’t going back to New York. This was going to be it. He could just imagine the chatter in the press box right above him.

Hell, Williams thought, those idiots ought to be happy. They’d been trying to retire me for years. By now, Williams knew their ritual. Ted would come to spring training and see the “Is this it for Ted Williams?” stories, suffer through the “Williams’s slow start may mean he’s finished” stories that were sure to appear in the cold early months when Williams never hit his best, then expect the “Will Red Sox invite Williams back for one more year?” stories in the fall.

In a town with, at times, seven newspapers and a rabid—some might say unhealthy, baseball interest, Williams was always somebody worth writing about. Hell, at least one of them admitted it.

“The loss of Williams to a Boston sports columnist is like a bad case of athlete’s fingers to Van Cliburn,” wrote John Gillooly of the Boston Daily Record. “You just can’t pound the keys any more. The song is ended.

“I am not going to crank through the microfilms of the Daily Record for the past year. . . . But I’ll guess that if I wrote 280 columns in that 12-month [span] that 80 of them were about The Kid, the chromatic, bombastic, the quixotic—a demon one day and a delight the next. . . . Williams made columning easy.”

Yeah, they were going to miss Ted Williams, all right. Even the bastards who hated him as much as he hated them. The thing was, nobody ever called them on any of the shit they wrote, even when they were dead wrong. Ever.

Williams thought back to Bill Cunningham’s analysis of his swing, back when he was a rookie. Williams could remember it word for word. He had that kind of recall if something ticked him off enough. And many things did.

“The Red Sox seem to think Williams is just cocky and gabby enough to make a colorful outfielder, possibly the Babe Herman type,” Cunningham wrote. “Me? I don’t like the way he stands at the plate. He bends his front knee inward, he moves his feet just before he takes a swing. That’s exactly what I do just before I drive a golf ball and, knowing what happens to the golf balls I drive, I don’t think this kid will ever hit half a Singer midget’s weight in a bathing suit.”

What a horse’s ass. But who ever called them on it?

Once Williams learned the newspaper game, Ted fought back in his own way from time to time. Like giving an exclusive interview to the out of town guy, knowing full well that the Boston guys would catch wind of it and be pissed off that he gave someone else the scoop. That was a real “Kiss my ass” to the boys on the beat.

Williams loved to do that. Or after a disagreeable article, maybe he’d get in their face, tell ’em he smelled something awful in the locker room, then tell ’em it must have been the shit that they were writing.

And the stuff they wrote in the offseason, why, it was unbelievable. Williams feuding with his brother, Williams refusing to visit his mother in the offseason, Williams not being at the hospital for the birth of his daughter— there were so many more. Why was he the only player anywhere who had to deal with that crap?

More than once Williams wondered why the hell didn’t they write that stuff about DiMaggio? Hell, DiMaggio was a great player but also out until all hours at New York nightclubs, banging showgirls left and right, a different one every night, drinking and smoking with the New York newspaper guys, calling them his pals. They write about him like he’s a god. Hell, DiMaggio had had his failed marriages, too. How come nobody ever wrote about that?

Even Red Smith, whom Williams liked, always fawned over DiMaggio. He remembered one time Smith wrote that DiMaggio was “excelled by Ted Williams in all offensive statistics and reputedly, Ted’s inferior in crowd appeal and financial standing, (yet DiMaggio) still won the writers’ accolade as the American League’s most valuable in 1947. It wasn’t the first time Williams earned this award with his bat and lost it with his disposition.”

Well, that was true enough, Williams thought. But what does your personality have to do with what you do with a baseball uniform on? Can you play, can you hit or not? Was it a popularity contest or not? Writers, can kiss my. . . .

But his relations with the press cost him. In 1942, Williams won the Triple Crown and lost the MVP to one of the Yankees, Joe Gordon, who hit .322 to Williams’s .356, drove in 103 runs to Ted’s 137. Even in 1941 when Williams hit .406 with six hits on the final day of the season, DiMaggio got the award for his 56-game hitting streak.

Williams always tried to be gracious about it. Joe was a great ballplayer. But he had to wonder what the New York media blitz did for Joe on a regular basis. Even Red Smith, for chrissakes. “As a matter of fact,” Smith continued in that same article, “if all other factors were equal save only the question of character, Joe would never lose out to any player. The guy who came out of San Francisco as a shy lone wolf, suspicious of Easterners and Eastern writers, today is the top guy in any sports gathering in any town. The real champ.”

Were we supposed to bow when DiMaggio comes up? Williams laughed. Nobody ever puffed up Ted Williams that way. How much did DiMaggio do for charity, anyway?

Anybody ever ask that question? Ah, it didn’t matter. The people at the Jimmy Fund knew who Ted Williams was and how much he cared and how much he helped kids. The hell with the New York press. The more Williams thought about what happened to him in Boston, it wasn’t fair. Not that he could ever say it. Then they’d really let him have it.

Sure, he was a hot head and ill-tempered and childish and foul mouthed and ill behaved and you bet your life he’d go at those sons of bitches. But how come we never found out what kind of dad, what kind of son, what kind of husband DiMaggio was? The Boston writers all had to know all that about Ted. Why didn’t the New York writers want to know that about Joe? It was a fair question.

One year, a Boston writer called Williams’s ex-wife to find out what he’d bought his kid for Christmas! They didn’t pull that crap with DiMaggio. If any one of them wrote a single word that DiMaggio didn’t like, he’d cut them off. And they’d be out of a job. Don’t think DiMaggio didn’t know it.

Hey, if you’ve got that kind of clout, why not use it? No knock on Joe. But you’ve got to wonder how would he have done with the Boston press? As nervous as he was? What would they have done with his legend? Especially near the end when he couldn’t hit or play center field like he always had.

Many years later, the respected journalist David Halberstam, a Williams fan, talked with famed sportswriter W. C. Heinz about DiMaggio and how the New York press handled him. “I had been around DiMaggio a good deal,” Heinz said, “I knew how most of the reporters played up to him, I knew how difficult he could be, and how coldly he could treat writers and how he would cut them off if he was displeased.”

Contrast that with Williams’s treatment by the voracious Boston press, as Halberstam would later note, not one of the shining moments in American journalism, and you have a much more complex picture. And when, in 1959, an assortment of injuries knocked Williams down to just .254—hell, he was under .200 until the midsummer—the writers were just savage. It got so bad that even Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey told Ted he ought to retire.

Nobody, not even Yawkey was going to tell Ted Williams what to do. He was still eight home runs short of 500 and he wanted to get there, for sure. He decided he’d take a pay cut, a pretty good one—$35,000—from his $125,000 annual salary (wonder if DiMaggio would ever do that?) and worked himself into good shape when the year began. He’d show those sons a bitches who was washed up.

He blasted a home run in his first at-bat and hit all year long. And so, well, it was all over now as he approached the Fenway Park batter’s box for the final time. It had been quite a day, Williams thought, taking one long last look around Fenway Park. He knew the writers were grousing about him right now up in the press box, those “knights of the keyboard,” as he’d called them in that brief pregame ceremony.

Screw ’em. There was no way he was going to let them off the hook at that pregame ceremony earlier today. They hurt too much. Too often. Somebody was going to call them on what they wrote. This was his last chance.

He knew it was supposed to be a happy, classy day but damn, he stood at the microphone by the pitcher’s mound, sort of shifting his weight uneasily from one foot to the other and just let it go. He couldn’t help it.

“Despite the fact of the disagreeable things that have been said of me— and I can’t help thinking about it—by the knights of the keyboard up there, baseball has been the most wonderful thing in my life. . . .If I were starting all over and someone asked me where is the one place I would like to play, I would want it to be Boston, with the greatest owner in baseball and the greatest fans in America. Thank you.”

That was his final shot in the war with the press. He was sure they’d fire back one last time. But Ted Williams just didn’t know how to let anything go, and he wasn’t going to start now. He heard his name announced for the last time and he started toward the plate. He could hear the crowd now, roaring, applauding, without a single boo in the house.

He laughed. He always used to be able to pick out that boo. He hefted the bat and thought to himself, “one more time, one more time.” He’d started the season, this final season, with a home run in his very first at-bat, a 450- foot shot off Camilo Pascual. Wouldn’t it be something if he could go out with one, too?

He stepped into the batter’s box and Fisher deferentially waiting until the cheers died down, wound and threw. Ball one. Williams, who rarely swung at the first pitch, was ready for a fastball and here it came. He uncoiled and swung mightily at it. Plop. He heard the ball land in Gus Triandos’s glove. Strike one.

The crowd rumbled and buzzed around him. This was a challenge. Take that, you old bastard.

“The pitcher’s always the dumbest guy in the ballpark,” that was one of Williams’s favorite lines.

He dug in. He knew what he was going to get next. Just knew it.

Fisher snapped his glove at Triandos’s return throw as if he was eager to get another pitch headed homeward. He wound and threw—it was another hard fastball—and Williams let loose with the final swing of his glorious career and caught it flush.

The crack of the bat, an unmistakable sound when Williams hit one right, rang through the park and the 10,000 came to their feet as the ball soared deeper and deeper toward the right field bullpen, toward Williamsburg, they used to call it.

Suddenly, it descended with a rush, clunking off the canopy over the bullpen. Home run. Goodbye.

Some time later, novelist John Updike, a Williams fan, wrote a piece about Williams’s final game. He caught that moment perfectly: “He ran as he always ran out home runs—hurriedly, unsmiling, head down, as if our praise were a storm of rain to get out of. He didn’t tip his cap. Though we thumped, wept, chanted, ‘We want Ted!’ for minutes after he hid in the dugout, he did not come back. . . . The papers said that the other players, even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way. But he refused.”

Immediately after the game, though, Williams was in no sentimental mood—at least not to share with the newspapers. Reporter Ed Linn noted that Williams was pleasant enough with the first wave of reporters. Those he liked came to his locker first. They got the good Ted. “I was gunning for the big one. I let everything I had go. I really wanted that one,” he said, smiling.

By the time those Williams wasn’t as tolerant of arrived—including Linn—his mood had soured. What little goodwill he had toward the press had evaporated. Linn asked Williams if he’d thought about tipping his cap when manager Mike Higgins had sent him back out to left field at the start of the ninth inning, only to have Carroll Hardy immediately replace him amid a roaring, foot-stomping ovation. Wasn’t that heartwarming?

It was the writer’s way of asking, didn’t Williams really want that ending where everybody goes home happy? Williams wasn’t playing that game. “I felt nothing,” Williams said. No sentimentality, the writer asked? “I said nothing. Nothing, nothing, nothing.”

And he knew what they’d say in the papers, too. That he was going to go to New York until he hit that home run, then decided to quit then and there. The bastards. He told Higgins, he didn’t pack for the trip to New York, he’d made up his goddamned mind before the game that this was it. Period. But they’ve got to have a little controversy.

And that Kaese, Harold Kaese from the Globe, he knew he’d find a way to go after him, too. He did too, in his column in Thursday’s Globe. Sure enough, here was Kaese making sure to mention Harry “The Cat” Brecheen, who’d stopped Williams in his only World Series appearance against the Cardinals in 1946, a guy who happened to be standing and watching Baltimore’s Steve Barber warm up. Gee, he was a key component of the final game story, wasn’t he?

Then Kaese mentioned that more people had seen Williams play his first game at Fenway—his American League opener—or his first “farewell” in 1954 than this game. Then Kaese speculated on what some of his press box colleagues (including himself ) might write for the next day’s headlines, “Sox Pennant Hopes Soar, ( Jackie) Jensen returns, Williams retires.”

Then there was this. Low by even Kaese’s standards. His description of Williams crossing the plate after his dramatic final home run. “For Fisher, Gus Triandos, and Umpire Ed Hurley, Williams had a smiling curtsy as he touched the plate. Was Fisher ‘piping’ the ball for Williams? Some wondered. He threw nothing but fastballs his last two times up, but one had so much on it that Williams fanned it just before he homered.”

Williams started to get angry when he read it. Then he laughed. Kaese had questioned the purity of the home run, the timing of Ted’s retirement, slammed him about the Red Sox’s failing attendance and his own rotten World Series 14 years earlier, all in a single column.

Kaese left Ted Williams with a home run too. What did Williams really feel about it all? That wasn’t going in some friggin’ newspaper. Not a Boston newspaper, that’s for sure.

It wasn’t until years later that he lowered his guard with TV’s Bob Costas. “I have to say that was certainly one of the more moving moments, the tingling in my body, that I ever had as a baseball player, that last home run,” Williams said. “That it was all over and I did hit the home run.”

Williams also explained that final at-bat in more detail. After he’d swung and missed that 1-0 fastball—the wire services ran a shot of Ted flailing at it, eyes closed, bat outstretched, his picture-perfect swing looking awkward and old—he saw something in Fisher’s manner that flipped a switch.

“So here I am, the last time at bat,” Williams told the Baseball Hall of Fame some years later, “I got the count one and nothing and Jack Fisher’s pitching. He laid a ball right there. I don’t think I ever missed in my life like I missed that one but I missed it. And for the first time in my life I said ‘Oh Jesus, what happened? Why didn’t I hit that one?’ I couldn’t believe it. It was straight, not the fastest pitch I’d ever seen, good stuff. I didn’t know what to think because I didn’t know what I’d done on that swing. Was I ahead or was I behind? It wasn’t a breaking ball and right in a spot that, boy, what a ball to hit. I swung, had a hell of a swing, and I missed it. I’m still there trying to figure out what the hell happened. Then I could see Fisher out there with his glove up to get the ball back quickly, as much as saying ‘I threw that one by him, I’ll throw another by him.’ And I saw all that and I guess it woke me up, you know. Right away, I assumed ‘He thinks he threw it by me.’ The way he was asking for the ball back quick, right away, I said, ‘I know he’s going to go right back with that pitch.’”

So Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived, sat back and waited for one more, one last, fastball. Then he hit it out of sight, ran around the bases and never tipped his cap, never looked back even when they screamed and clapped and stomped and hollered his name.

He heard them all right. But he sat in the dugout and pulled on his jacket. “Gods,” John Updike famously wrote a few months later, “don’t answer letters.”

Months later, when Williams saw Updike’s story, you can bet he was laughing. “Gee, I wonder if Joe D. saw that line about Gods and letters. . . .”

Ted Williams by the Numbers

About the author:

John Nogowski grew up in New Hampshire, worked in the newspaper business for 25 years in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Michigan, Florida and Georgia. He taught as an adjunct professor at Florida State University, Tallahassee Community College and Bainbridge State College before settling in at Gadsden County High School in Havana, Florida for a dozen years, retiring in 2022. His student newspaper, the Gadsden County Gazette was a two-time National Scholastic First-Place Winner in high school competition. “Last Time Out” and “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Annotated Discography 1961-2022” are updated editions of earlier books. “Last Time Out” originally appeared in 2005. This updated edition includes 18 new chapters, including a final chapter about his son's first MLB game. “Bob Dylan” is the third edition of a comprehensive work done for McFarland and Co., covering Dylan's long career. Earlier, Nogowski wrote “Teaching Huckleberry Finn” about his experiences teaching Twain's classic work in a minority high school setting.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.