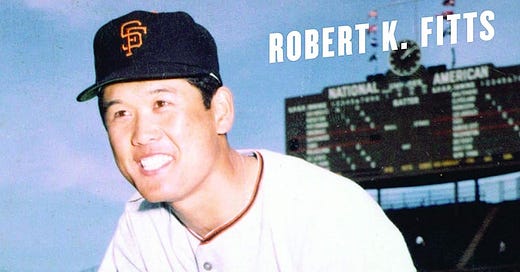

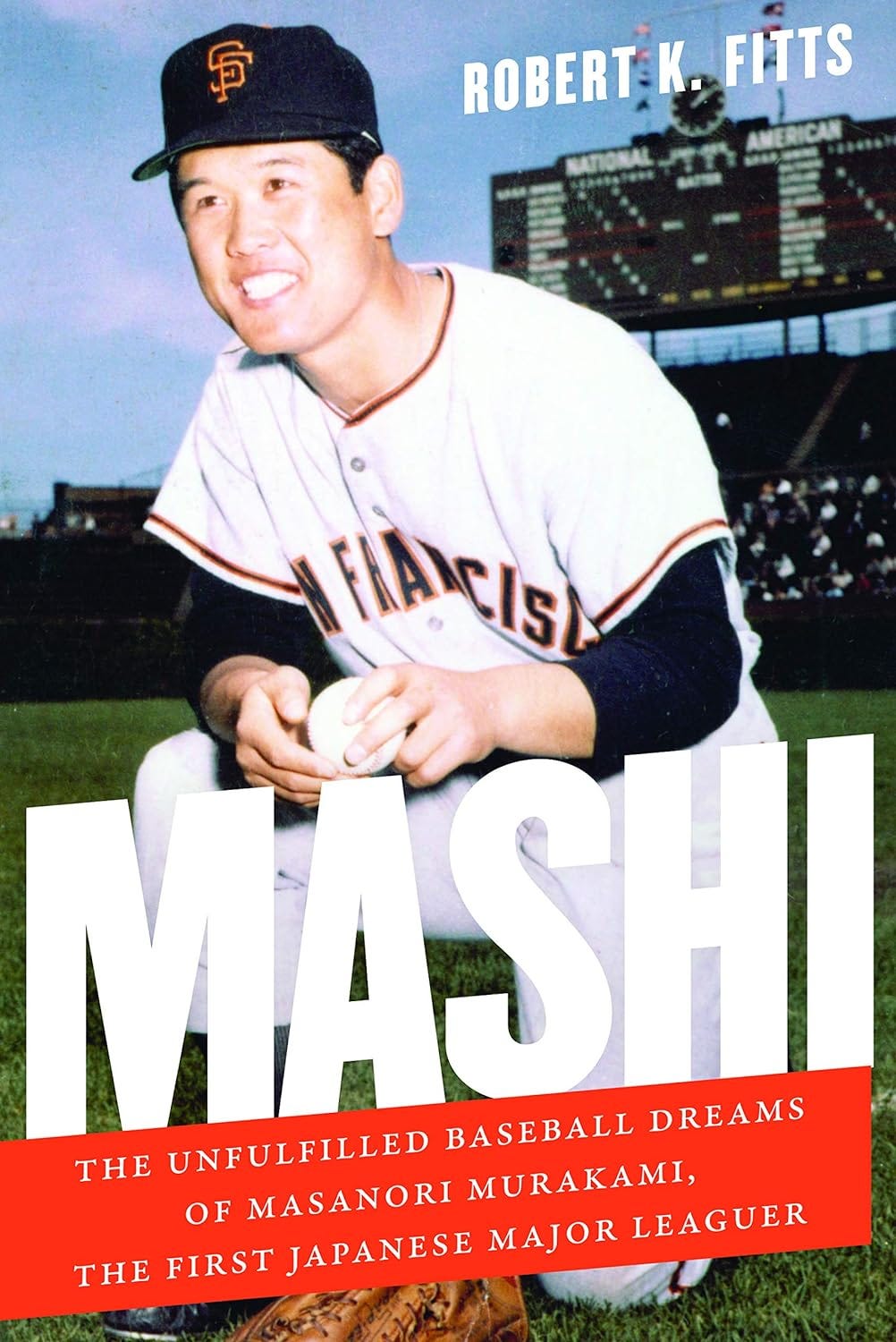

Book Excerpt: Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major League

Plus ICYMI, Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

Long before Shohei Ohtani first toed the rubber in Anaheim — 54 years before, to be precise — a reliever by the name of Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese player to appear in the major leagues.

After a fine showing as a 20-year-old in a September 1964 callup (1.80 ERA, 0.600 WHIP) Murakami spent the bulk of the 1965 season in San Francisco, pitching in 44 games, finishing 16, with one save, a 3.75, 1.063 and 85 K in 74 1/3. But it wasn’t easy, and after the experience in American ball, the left-hander returned to Japan where he enjoyed a fine 18-year career with the Nankai Hawks and Nippon Ham Fighters.

Today, we celebrate Murakami‘s story. With number 25 in our book excerpt series, I am happy to recommend “Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer,” by Robert K. Fitts (University of Nebraska Press, April 1, 2014, Hardcover $16.19, Paperback $18.95, Kindle $15.38).

There are 64 mentions of the Dodgers in Mr. Fitts’ book, with the final two chapters devoted entirely to the 1965 National League pennant race, which ended happily for Los Angeles. I have chosen one of those chapters to excerpt here, which you will find after the jump.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 17:

Masanori stood, hands on hips, on the grass behind home plate. He shifted his weight impatiently from foot to foot as a dozen men in suits scurried around him. In a few minutes he would be starting his first Major League game, and he wanted to prepare for the challenge. At the same time he was excited to be honored and thrilled by the sports car, now covered by a white sheet and tied with a red ribbon, parked behind him. The newspapers had announced that Kikkoman International, the soy sauce company, would be giving him a brand new Ford Mustang convertible.

Nearly twenty-seven thousand fans had come to Candlestick Park for Masanori Murakami Day. The crowd included about a thousand Japanese Americans, over a tenth of the Bay area’s Nikkei population. More might have attended if it had not been for the appalling news coming from Los Angeles. Four days earlier a routine traffic stop in the city’s Watts neighborhood had escalated into a full-scale riot. For six days over thirty thousand African Americans battled police and National Guard units in the streets of Watts. Nearly three hundred buildings burned to the ground as opponents exchanged gunfire and snipers prevented firefighters from extinguishing the blaze. Over a thousand people would be injured and thirty-four would lose their lives. Fear that the unrest would spread to other cities and a fascination with events kept many Americans in their homes.

Soon the ceremony began. Officials presented Mashi with plaques from the Vallejo, California, Elks Club and the Japanese American community of northern California. Greetings, telegraphed from San Francisco mayor John Shelley and California governor Edmund G. Brown, Sr., were read over the PA system, and Japanese consul general Tsutoru Wada gave a brief speech, telling the fans, “Baseball is just as much a part of our life in Japan as it is in the United States.” Masanori’s speech was short and to the point. “Thank you,” was all he said.

After the speeches, kimono-clad Judy Sugihara presented Masanori with the keys to his new car. By now whatever apprehension he had had about not preparing for the game had vanished. “I was so happy to have a car that I wasn’t thinking about the game so much,” he recalls. With a flourish the sheet came off, and Mashi looked down on his new . . . Datsun.

Masanori probably blinked with surprise. Where was the Mustang? At the last moment Consul General Wada had pressured Kikkoman International to give Murakami a Japanese rather than an American car to help publicize the nation’s emerging automobile industry. Later in the season Murakami, with a big sigh, admitted to a reporter from the Nichi Bei Times, “I wish it had been a Mustang.” Bringing a car to Japan involved large transportation and import duties, “but it would have been worth it for a Mustang,” he added with another big sigh. Nonetheless, he hopped in the light blue Datsun with “good luck Murakami Kikkoman” stenciled across the driver’s side doors and with a wide grin, waved to the fans and photographers.

After the ceremony Masanori warmed up as Bob Courier, the Spaceman, flew across the diamond in a jet pack. Years later baseball writer and former beat reporter Charles Einstein would write, “Totally dependent on his teammates for schooling in the English language, he [Murakami] nevertheless wished to preserve the baseball custom of his homeland, under which the starting pitcher would greet the plate umpire with a courteous salutation. Came now in 1965 Murakami’s one and only starting assignment, and his fellow Giants had primed him in advance. Striding out from the dugout to take the mound, Murakami paused and bowed to the plate umpire. ‘Herro, you haily plick,’ he said. ‘How you like to piss up a lope?’ The umpire, Chris Pelekoudas, found himself bowing back. ‘I couldn’t think of what else to do,’ he explained.”

Like many of the reporters’ “humorous” Murakami stories, Einstein’s tale not only pokes fun at Mashi’s poor English but also portrays him as a gullible rube—a common ingredient in most ethnic stereotypes and ethnic jokes. Also like most of the other stories, it is completely untrue. Murakami denies that the event occurred, noting that by August his English was pretty good, so he would not have asked his teammates for advice on what to say. Even if he had asked, he would have known that he was being set up, as he “had learned all of those words in spring training the year before.” Furthermore, records indicated that Chris Pelekoudas was in Chicago that afternoon umpiring third base as the Cubs faced the Braves.

Instead of swearing at the umpire, Masanori merely took the mound and finished his practice pitches. Since the two games against the Reds in late August, Franks had used him often, and he had not pitched particularly well. Playing nearly every other day, he had entered 7 games, totaling 9⅔ innings, and recorded 2 saves. At times his signature sharp control was absent. He had walked 5 and thrown 2 wild pitches. He had also surrendered 6 earned runs. Yet today he felt ready, even though Gene Mauch, the wily Phillies manager, had stacked his lineup with right-handed batters. Star right fielder Johnny Callison would be the only left-hander to face Murakami.

It would be Callison who would get the first hit off Mashi. After he had retired leadoff batter Cookie Rojas, Callison and Dick Allen hit consecutive singles to put runners at the corners. He later told reporters that he “might have been overexcited about starting.” Steadying himself, he then struck out both Dick Stuart and Alex Johnson to end the inning. The second inning went smoothly for Mashi as he struck out Adolfo Phillips looking and Pat Corrales swinging and forced Bobby Wine to foul out to third baseman Jim Hart.

In the bottom half of the inning Mashi came to bat with two out and runners on first and third. A hit would give him the lead and a chance for a win. He battled Phillies starter Ray Culp and pulled a pitch into right field. Callison, however, caught it for the final out.

As he took the mound to start the third, adrenaline rushed through Murakami. He had already struck out four, and Culp, the pitcher, would lead off. He should be able to strike him out as well, he thought to himself. “I got carried away, “he remembers, “and that was not good.” Trying too hard for the strikeout, Mashi overthrew and lost the strike zone, walking Culp. Rojas then ripped a single to center field. After Callison grounded into a fielder’s choice, Dick Allen blasted a triple to center field, driving home the two runners. Giving Murakami surprisingly little leeway, Herman Franks brought in Ron Herbel to finish the inning. He fared little better, giving up a walk, three singles, and another two runs (one charged to Mashi’s ERA).

After being knocked out, Masanori showered and watched from the press box as the Giants made an impressive comeback. In the bottom of the third Jim Hart hit a grand slam to put the Giants ahead 4–3. Murakami breathed a sigh of relief. “I was so happy because I didn’t want to lose on the anniversary of Japan’s defeat in World War II. It would have been like being defeated all over again.”

In the fifth Willie McCovey hit a three-run “off-the-plate home run.” With Matty Alou on second and Mays on first, McCovey hit the ball straight down. It bounced off the plate straight into the glove of Phillies pitcher Bo Belinsky, who nonchalantly fielded the ball and “fired it something like 40 feet over the head of the first baseman” into right field. Alou scored easily and Mays barreled home just ahead of the relay throw. Catcher Pat Corrales, however, believing that he had tagged Mays before he touched the plate, began arguing with umpire John Kilber. Completely forgotten, McCovey continued to circle the bases. Finally eyeing him rounding third, Corrales heaved the ball down the line, well beyond the bag and into left field. McCovey jogged home for the Giants’ ninth run. Two innings later McCovey hit a true 400- foot home run over the center-field screen to push the score to 13–4. In the end the Giants would win 15–4, and in the words of Charles Einstein, “It was hard to remember that Murakami had started at all.”

Indeed Mashi’s anti-climactic performance on his well-publicized day led a reporter who had traveled all the way from Tokyo to spice up the story. The Japanese tabloid reported that Mashi was in the midst of a torrid romance with Judy Sugihara, the attractive young lady who had presented Masanori with the keys to his new car before the game. According to the story, Miss Sugihara, who was the daughter of the president of Kikkoman International, had “begged her father to give her athlete-boyfriend a car for a present on his day.” When told of the story by Japanese American reporters, Murakami responded, “It’s a shame how they make up stories about big-name players, just to sell more copies of their paper.”

The Japanese tabloid was not the only newspaper interested in Mashi’s romantic life. Several American reporters suggested that the Giants find Masanori an American girlfriend to make him want to stay in the United States, and a few others, picking up the false report on Judy Sugihara, wrote that he was already deeply in love. The truth, however, was far less interesting. “I never thought of having a girlfriend, nor did I have the time to have one during the baseball season,” Mashi later told Shukan Baseball. “I went to dinner with a lot of people—five or six—but not on a date.” Cultural differences, as well as Yoshiko Hoshino, kept Murakami unattached. “I think the girls here are very open,” he told American reporters. “They live alone in apartments. I don’t understand this. Maybe in Japan if a girl lives far away from her parents, she lives in an apartment. Here a girl lives in the same town as her parents—almost the same block—but she lives in an apartment. If she wants to go out—[she just goes] out! In Japan she must ask her parents [first]. I think that’s better.”

With all the attention he received on Masanori Murakami Day, reporters began pressing Mashi on his plans for the 1966 season. “I don’t know yet what I will do. It is very good here with the Giants, very nice,” he stated in early August. “I’ve enjoyed playing in the United States very much. The people have been good to me, and I have had no serious problems,” he added directly after his start.

“The Giants [players] would like nothing better than to have the personable lefty back,” reported the Hokubei Mainichi. “He is one of the best-liked players on the club with his happy disposition, and as far as communication is concerned his teammates say there is absolutely no problem. His English is more than proficient, his mates claim.”

Mashi bonded with the other two youngest players on the team, nineteen-year-old Ken Henderson and twenty-year-old Bob Schroder. Henderson recalls, “Masanori had such a great personality and a great sense of humor. He was really fun-loving, so he was well accepted. He was always eager to learn, asking questions. He was very inquisitive and anxious to learn about so many different things. He wanted to know what American baseball was about. What the big leagues were like. What should I be doing? What is the right etiquette? We would walk the streets of New York City, and he would go into certain stores just to see how people merchandised things. He would go to different restaurants to find out about different cuisines.”

Henderson and Gaylord Perry had taught Murakami to play gin rummy. He picked up the game easily and soon became very good. On road trips the team would often leave one city after a night game and travel through the night to the next destination. Unable to sleep on the short flights, the three would play cards for hours. Perry, who would later admit to throwing the spitball and doctoring baseballs with illegal substances such as Vaseline, would sometimes need his cunning to beat Mashi. Murakami would usually take a window seat; Perry would take one on the aisle, and they would leave the middle seat open to play cards. One night Henderson, walking down the aisle, asked Masanori how the game was going. “Ah, he beat me too much. He beat me too much!” he replied. Perry had just taken about a dozen straight games. “Masanori, look in your window!” exclaimed Henderson. The Japanese pitcher’s cards were reflected in the window and Perry could see them all.

While on the road, ballplayers have little time for leisure. Days are filled with practice, nights with games and travel. Mostly they eat, sleep, and play baseball. Masanori would occasionally see a movie with Henderson and Schroder. His favorites were cowboy films, and he would stop everything when Rawhide came on the television. “But I didn’t go out with the team members a lot,” remembers Murakami “because there were always people coming to fetch me.” On nearly every road trip local Japanese would come to the hotel, introduce themselves to Masanori, and take him out to see their town. One time when the Giants were in New York, for example, a couple of Japanese Americans telephoned him at the hotel.

“We came from Boston to watch you play. If you have time, why don’t we show you New York?” Without hesitating, Mashi said, “Okay!” They were complete strangers, and now Murakami muses, “I could have easily been kidnapped!”

They brought Masanori to the Statue of Liberty and other landmarks before closing out the tour with a drive through Harlem. In 1965 the area was not the mecca of African American culture that it had been in the 1920s or the thriving commercial and cultural district of today. It was a neighborhood characterized by poverty, decay, and racial tension that had erupted the previous summer in deadly race riots. It was also a common destination for the more adventurous tourists, who wanted to see “the ghetto” through the rolled up windows and locked doors of their automobiles.

Even for a foreigner like Murakami, who could not read the newspapers and had no interest in politics, the racial tensions of the times were impossible to escape. When a Japanese reporter asked what he thought of Willie Mays, Mashi began with a surprisingly candid comment. “Generally speaking, in the United States black people are kind of looked down upon, but I personally don’t regard them as such. He [Mays] is a very good person. He gave me a lot of advice. . . . He also cheered us young people on; he was always thoughtful of the young players and helped us a lot.” When asked the same question about Murakami, Mays told American reporters, “He’s a good boy. He’s learning all the time. He likes to give you the impression he doesn’t understand English and he doesn’t know one hitter from another, but he knows what he’s doing.” Besides, “language has nothing to do with our friendship. Murakami and I are good friends, so good that we may not need a language between us.”

Sometimes the Giants’ captain would invite teammates to his home for dinner parties. Japanese rarely entertain business associates, or baseball teammates, in their homes. Instead men will invite associates to a restaurant or club. Masanori, therefore, found these invitations particularly enjoyable. Mays’s home at 54 Mendosa Avenue in the predominately white, but heavily Jewish and Catholic, Forest Hill neighborhood was called “the most extravagant bachelor’s pad in San Francisco.” Built on a steep slope that overlooked the Golden Gate Bridge, the two-story ultra modern house was relatively small, containing just seven rooms in 2,106 square feet but was decorated with the opulence of an eighteenth-century French noble. Thick, expensive gold carpet covered the floors; fine Austrian white drapery framed the windows. Six of the seven rooms contained a television set.

One afternoon Mays invited some of the Giants and their families over for a barbeque. Mashi sat in the yard talking to his teammates. “It was a relaxed atmosphere, and I felt very comfortable, as you do with old friends. Willie told me to come with him and we went into the house, up to his bedroom on the second floor. He went to his closet, opened a drawer, and pulled out a pair of cufflinks with diamonds and rubies on them. “Here,” he told me, ‘I want you to have these.’”

Although Mays had little trouble purchasing the house on Mendosa Avenue in 1962, he told Murakami of the difficulties he had encountered when he had tried to buy a home in a white neighborhood in 1957. Real estate agents would not return his calls, homes were taken off the market when he showed interest, and an offer was flatly refused on the grounds that selling to an African American would lower neighborhood property values. Later in his life Murakami realized that Mays was warning him that although the baseball fans loved him, as an Asian he might still encounter discrimination in the United States.

After Mashi’s poor start against the Phillies, reporters asked Herman Franks if Murakami would get a second chance. No, responded the manager. He was the club’s top left-handed reliever. “It’s not that Mashi did so badly, it’s just that he’s much more valuable in the bullpen.”

In the upcoming series against the Dodgers, Mashi would prove Franks right. The Dodgers arrived in San Francisco on August 19 for a four-game series. The California press had been hyping the games all week, calling them “the Fight for First Series” as Los Angeles’s NL lead had slowly dwindled. By the start of the first game, the Dodgers had actually fallen into second place, a half game behind the Milwaukee Braves. The Giants, a half game behind Los Angeles, hoped to leapfrog into first.

The opener featured Don Drysdale against forty-four-year-old Warren Spahn in his last year of professional ball. The grueling game lasted four hours and eleven minutes before the Dodgers scored three in the fifteenth to capture the victory. It might have been over much sooner if Murakami had held the visitors in the seventh inning. With a 3–2 lead, a runner on first, and one out, Franks brought in Mashi to relieve a tiring Spahn. He struck out Willie Davis looking but then surrendered a double to catcher John Roseboro that tied the game. It was only the third time all season that Masanori had not protected a lead. The next morning the headline of the Bakersfield Californian blared, “Dodgers Draw First Blood in Big Series.” As most baseball fans know, more blood would flow later.

On the surface the second game seemed uneventful. Bob Shaw pitched a complete game as the Giants won easily, 5–1. The newspapers reported no beanballs or altercations, but an exchange occurred that would have violent consequences. In the fourth inning Maury Wills faked a bunt but pulled back the bat at the last moment, hitting catcher Tom Haller in the process. It was an old but effective trick, and umpire Al Forman awarded Wills first base on catcher’s interference.

The following inning Franks ordered Matty Alou to attempt the same ploy. Alou pulled the bat back at the last instance but failed to hit Roseboro. The pitch, however, struck the catcher firmly in the chest protector. “You weasel bastard!” Roseboro cursed at Alou, followed by a threat. Hearing the comments, Franks and Juan Marichal berated Roseboro from the Giants dugout. Expletives and threats flew back and forth, ending with Roseboro yelling at Marichal, “The next time something like that happens, you’re going to get hit in the head with the ball!”

Tempers seemed to calm during Saturday’s game. Another thriller, the Giants led 3–2 with one out in the seventh when Roseboro homered off starter Bob Bolin to put the Dodgers on top 4–3. Franks immediately brought in Mashi to keep the game close, and he struck out pitcher Bob Miller and Maury Wills to end the inning. He would only pitch to the two batters, as Franks removed him for a pinch-hitter in the bottom half of the inning. The Giants would go on to tie the game at four before eventually losing in the eleventh inning. The win put Los Angeles back in first place, a half game ahead of the Braves and a game and a half above the Giants.

The matchup on Sunday, August 22, between Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal brought 42,807 fans to Candlestick Park to witness one of the most infamous moments in baseball history. Trouble began with the first batter. Leading off, Maury Wills laid a bunt down the first baseline, beating the throw for a single. After advancing to second on a ground out, he scored on a Ron Fairly double. Marichal apparently took exception to Wills’s “cheap hit,” and when he came up again in the second inning, the Giants’ ace knocked Wills to the ground with a high, tight fastball before retiring him for the third out.

Willie Mays led off the bottom of the second. To pay back the Giants for knocking down Wills, catcher John Roseboro signaled Koufax to come in high and tight to Mays. Koufax, who as a rule did not throw at hitters, fired a fastball well over Mays’s head instead. Although harmless, the pitch satisfied baseball’s unwritten rule that a knockdown pitch had to be answered. With the inside pitch to Wills revenged, at least symbolically, the teams were even, and play should have continued normally.

But the following inning Marichal threw a tight fastball to outfielder Ron Fairly. Marichal later claimed that it was not intended as a brushback pitch, but the Dodgers saw it as a clear violation of baseball etiquette—Koufax’s pitch to Mays was supposed to have ended the knockdown pitches. Dodgers screamed at Marichal from the dugout. With Koufax unlikely to respond, Roseboro vowed revenge.

Marichal led off the bottom of the fourth inning with the Dodgers ahead 2–1. Knowing that Koufax would not throw at an opponent, Roseboro decided to punish Marichal himself. The first pitch came down the middle for a strike. Roseboro tossed the ball back to the mound. Koufax wound up and delivered a ball, inside and low. Roseboro received the pitch, then deliberately dropped the ball just behind Marichal’s back foot. Picking it up, Roseboro fired it back to Koufax, grazing Marichal’s ear.

“Why did you do that?” yelled Marichal. You better not hit me with that ball!” Roseboro’s response was a stream of curses and comments on Marichal’s mother’s virtue as he took a threatening step toward the Giant. Marichal shoved the catcher aside, raised his bat above his head with both hands, and swung down, striking Roseboro on the head. The catcher fell to his knees, blood streaming from the wound. Marichal struck twice more before Koufax, third base coach Charlie Fox, and umpire Shag Crawford intervened.

Players from both teams charged to home plate—some to prevent further conflict, others to exact revenge. A season of tension between the teams boiled over. “Aroused to the point of blind fury, Marichal continued to swing his bat menacingly until forced away by Dodgers and teammates.” Giants rookie shortstop Tito Fuentes jumped into the fray, wielding his own bat. Dodgers outfielder Lou Johnson threw punches at any Giant he could reach. Others pushed, shoved, wrestled, and punched. Mays also rushed into the melee, straight for Roseboro. But instead of delivering a blow, the Giants’ captain, “with tears in his eyes and blood splattered on his uniform, held Roseboro’s shoulders, restraining him.”

Murakami had been watching the game from the bullpen. He had seen Roseboro drop the second pitch and then looked away for a moment. Shouts brought his attention back to the plate. Marichal had already hit Roseboro, and other players had just reached the fray. Mashi and the other relief pitchers rushed from the bullpen. “Everything happened before I knew it. All the players ran out from both benches immediately. Mays was the first to run out. He ran to Roseboro and held him back from attacking Marichal. Koufax was running to home plate. Marichal’s friend, Fuentes, was jumping into the group, waving his bat. Mays’s uniform had turned red with Roseboro’s blood. It was crazy.” As he reached the edge of the fight, somebody pulled Mashi aside.

“You’re a pitcher,” he said. “Stay away from the fighting so you don’t get hurt.”

Following the instruction, Murakami stayed near the edge of the conflict, pulling an occasional shirt. “I was trying to think of something to say, but I couldn’t think of anything, so I just milled around the crowd of fifty players.” The brawl lasted about fifteen minutes before order was restored. Crawford ejected Marichal from the game, and Roseboro was helped off the field, his gash bandaged, and driven to the hospital for observation.

Undoubtedly rattled, or at least distracted, Koufax returned to the mound, walked two batters, and then gave up a home run to Mays. The Giants now led 4–2. Franks brought in Ron Herbel to pitch, and he shut down the Dodgers for five innings before running out of steam with one out in the ninth. A hit batsman followed by a single, put Wes Parker on third, Jeff Torborg on first, and brought Franks to the mound. With left-handed Wally Moon coming to the plate, Franks brought in Murakami. Dodger manager Walt Alston countered by pinch-hitting with right-handed rookie Don LeJohn.

Coming into the game, Mashi felt perfectly calm. Although the brawl had been terrifying to watch, the altercation had not involved him personally, and he bore no hostility toward the Dodgers. He focused on LeJohn, who bounced a ground ball back to the mound. Murakami fielded it, faked a throw to third to check Parker, and threw to Hal Lanier at second base to start a game ending double play. But Lanier, hurrying to make the play, dropped the ball. All the runners were safe and Parker scored. The Dodgers now trailed by only one run, had runners on first and second with one out, and had the top of the order coming up.

The dangerous Maury Wills entered the batter’s box. There would be little chance of the speedy shortstop hitting into a double play, while a successful bunt could load the bases. But “Murakami retired Wills on a windblown foul fly that Lanier snared near the Giant bullpen, then caught Jim Gilliam looking at a called third strike” to end the game. Looking back nearly fifty years later, Mashi would list saving the famous Marichal-Roseboro game for the Giants as one of his favorite memories in Major League Baseball.

The Giants emerged from the “Fight for First Series” just a half game behind the Dodgers, but the brawl, and Marichal’s subsequent eight-game suspension, seemed to sap the team’s drive. Embarking on a seventeen-game road trip, they lost four in a row in Pittsburgh, another to the lowly Mets, and then two of four in Philadelphia. Yet when they reached Chicago on September 3, they were just a game behind Los Angeles, which had suffered a similar losing streak.

After dropping the opening game against the Cubs, the Giants started to win. They began with the remaining three in Chicago and then took two from the Dodgers in Los Angeles. When Murakami retired Wes Parker on a fly ball to right field to save the Giants’ win on September 7, San Francisco moved into a first-place tie with the Dodgers. The following night’s win against Houston gave them sole possession of the top spot for the first time during the 1965 season. “This club is going to win the pennant,” predicted Warren Spahn. “Did you see them out there today? They were making some great plays. That’s the way it is with pennant winners. It’s what’s commonly called momentum. The players get to believing they’re going to win and they do. This club has just gotten that attitude in the last week or so, but they’ve really got it now.”

The Giants’ winning ways continued as they swept two from the Astros, four from the Cubs, and then four more from Houston. When they finally dropped a game on September 17 to the Milwaukee Braves, they had won fourteen in a row and were comfortably in first place with a 3½ game lead over the Dodgers. Rebounding from the loss, the Giants won the next three, increasing their lead to four games, with just a dozen left to play.

Willie Mays was the driving force behind the winning streak. Although his batting average dipped a few points during the fourteen games, he pounded out seven home runs, with a .722 slugging percentage. Teammate Warren Spahn noted that with the game on the line, Mays swung for the fences and invariably came through. “What impressed me was the way he went for the home run each time. A guy might settle for a base hit, but he was trying to tie it up. . . . The way he did it makes me wonder how good he could be if every time was a crisis.”

Out of the bullpen Murakami was superb. “The Giants never would be leading the pack now into the pennant stretch without him,” wrote Jack Hanley in the San Jose Mercury-News. After the start against Philadelphia until September 20, Mashi entered 14 games, pitched 22 innings, and surrendered just 15 hits, 5 walks (plus 3 intentional passes) and 2 earned runs. He also struck out 32 batters and picked up 4 saves. The raw statistics translated to a 0.82 ERA, a 0.91 WHIP, a 6.4:1 strikeout-to-walk ratio, and a .185 batting average against him.

Murakami was particularly effective against the rival Dodgers. Pitching in five of the six times the teams met after August 1, Mashi gave up just 1 hit and no runs in 5 innings. He also struck out 7 of the 18 batters he faced. “He’s deceptive,” an unidentified Dodger told the Oakland Tribune. “At first you don’t think he’s fast. Then he gets the ball over before you know it.”

On September 21 the annual San Francisco Giants’ late-season collapse began. They lost two to third-place Cincinnati, then two of three to Milwaukee. Meanwhile, the Dodgers went on their own winning streak. When the Cardinals came to town on September 27, the Giants and Dodgers were deadlocked at the top of the National League with identical 91-64 records. “So we just start all over, even with the Dodgers,” Herman Franks mused, “with seven games to play.”

The Giants, however, continued to lose—often in spectacular fashion. They dropped two of three to the Cardinals, including a 9–1 loss to rookie pitcher Larry Jaster and a 8–6 loss highlighted by Bob Shaw’s serving up a grand slam to opposing pitcher Bob Gibson. In each of these games the previously slick-fielding Giants made 3 errors. Shirley Povich of the Washington Post noted that the Giants “have been playing ragged baseball . . . [and] have suddenly become error-struck and as a pennant contender are more than faintly resembling the Mets.”

By September 30 the Giants had fallen two games behind the Dodgers when the Reds came to town to finish out the season with a four-game series. At first it looked like the Giants might bounce back. Juan Marichal had pitched seven strong innings when he turned the game over to Mashi in the eighth with the score tied at 2–2. Masanori was still pitching well and had not allowed an earned run in his last seven outings. After recording an easy first out, Murakami faced the dangerous power hitter Frank Robinson. Mashi started him off with a curve that failed to break. Robinson “smashed it high into the left field bleachers, but foul.” Murakami tried again. Once again the curve stayed flat, and Robinson slammed it down the left-field line. This time the ball stayed fair, and the Reds took the lead. Luckily the Giants staged a comeback, tying the game in the bottom of the eighth. After Mashi retired the Reds in the ninth, Orlando Cepeda gave Masanori his fourth win of the season with a walk-off “sayonara” home run. The next morning the Chronicle celebrated the rare victory with a large picture of Cepeda jokingly trying to land a kiss on a reluctant Murakami’s cheek.

Despite the win the Giants gained no ground on the Dodgers, who had now won thirteen straight games. The next day sealed the Giants’ fate. The onslaught began right away as starter Bob Bolin gave up two singles and two home runs before recording the second out of the first inning. Franks brought in Mashi to finish the first and hopefully help the Giants get back into the game. Tired from two innings the night before, Murakami was chased from the mound in the second after he surrendered a two-run homer to Pete Rose and a double to Vada Pinson. By the end of nine innings the Reds had pounded out 17 runs off eight different Giants pitchers. The following day, October 2, the Dodgers clinched the pennant.

Disappointed and fatigued, the Giants emptied out their lockers and packed up their belongings after beating the Reds in a meaningless game on October 3. Mashi gathered his things thinking that it might be the last time he would be in this room. He had brought a stack of shikishi with him and asked his teammates to sign the white cardboard squares with a felt-tipped marker. There was no end-of-the-season party or team meeting. Players drifted from the locker room after subdued goodbyes. Some told Mashi, “See you next season”; others said, “Goodbye.” It was time for Masanori to decide his future.

About the author (via Amazon):

A former archaeologist with a Ph.d. from Brown University, Rob Fitts left academics behind to follow his passion - Japanese Baseball. An award-winning author and speaker, his articles have appeared in numerous magazines and websites, including Nine, the Baseball Research Journal, the National Pastime, Sports Collectors Digest, and on MLB.com.

He is the author of five books on Japanese baseball. His next book, Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers will be published by the University of Nebraska in 2020.

Earlier books include Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (University of Nebraska Press, 2015); Banzai Babe Ruth (University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2008); and Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005).

Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the Annual Convention; and the 2006 Sporting News- SABR Research Award. He has also been a finalist for the Casey Award and a silver medalist at the Independent Publish Book Awards.

A popular speaker on the history of Japanese baseball, Fitts has spoken at many venues including the Library of Congress, the Japan Embassy in Washington DC, the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the Japan Society of New York, the Asia Society of New York, the Nine Baseball Conference, the Society of American Baseball Research Annual Convention, and the American Club, Tokyo.

While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese Baseball cards. He is now recognized as one of the leading experts in the field and has created the ebusiness Robs Japanese Cards LLC. He regularly writes and speaks about the history of Japanese baseball cards.

ICYMI:

The Dodgers are collecting an awful lot of infielders for a team that claims to be set with Gavin Lux at shortstop and Mookie Betts at second base. The team has acquired three shortstops this winter, including Trey Sweeney (.308/.400/.539 in the preseason), who could step in any time to field grounders and make normal throws to first base should he be needed. Because, and I’m sorry to sound like a broken record here, Gavin Lux simply cannot. While he hasn’t played short in his big league career, Andre Lipcius is the latest infielder to join the ranks, via Detroit for cash considerations Monday. He’s a 25-year-old righty swinger out of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, with a .266/.358/.409 slash line in four minor league seasons and a .286/.342/.400 in 13 games with the Tigers last year. He’s played left field, second base, third base and a bit of short in the minors. It’s a nice little pickup by Andrew Friedman and the front office.

Early camp cuts are as follows: Diego Cartaya, Hunter Feduccia, Nick Frasso (out for the year following shoulder surgery), Landon Knack, Andy Pages (pronounced pa-has), River Ryan and Ricky Vanasco have been optioned, with Stephen Gonsalves, Jesse Hahn, Michael Petersen, Eduardo Salazar and Travis Swaggerty being re-assigned. Vanasco, who I included in my Opening Day roster column, is a surprise to me. He’s working on a major league contract and has been essentially unhittable in three spring appearances. Meanwhile, Michael Grove can’t get anybody out, in exhibition action (11.57 ERA) or as a big leaguer (4.60 in 2022, 6.13 in ‘23).

Tweet of the Week:

Media Savvy:

FanGraphs’ 2024 top 49 Dodgers prospects list is out, penned this year by Eric Longenhagen.

Also at FanGraphs is Michael Baumann’s “We Don’t Need a Signing Window. Please Eat More Oatmeal.” And I couldn’t agree more. A free agent signing window is Rob Manfred’s latest bit of obnoxiousness floated for no other reason than to needle the players union. The stated purpose is that the commish wants to create early offseason interest in the game by mandating that free agents all sign be a certain date. An arbitrary date. The current system is better for both players and fans. I mean, what good does it do anybody but the 30 club owners to have all the signing action completed by, say, Christmas, with very little else occurring until Spring Training?

Since I’m on my soap box this afternoon, I was over my disdain for Rick Monday, who made an Everest-sized mountain out of mole (not a molehill; a mole!) during Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s Dodgers debut Wednesday until Fabian Ardaya wrote about it in the Athletic Sunday. The gist of the non-controversy is this: Broadcaster Monday, completely missing the point of the day, which was the exciting two-inning start by the new L.A. ace, in order to complain non-stop about what he perceived to be pitch tipping by the 25-year-old right-hander. And I’ve got news for you — it wasn’t pitch tipping. Or anything of the sort. Until such time as Major League Baseball sees fit to legalize Astros-like sign stealing, it’s not pitch tipping. Or until batters develop X-ray vision to see through leather in order to distinguish a fastball grip from a slider, whichever comes first. Sure, a camera operator can point a lens toward the mound to get a closeup view of a pitcher’s grip, but that’s of no use to an opposing batter. While I suppose in theory a runner at second base might be able to relay a sign in time to assist a teammate at the plate, Yamamoto faced no such situation, so there was no way to know if he’d hold the ball in his hand differently in such a case, and Monday made no mention of the rather obvious point. He was completely out of line, was still yapping his displeasure seven innings after Yamamoto’s exit and I wanted to smack him silly. I still do. The larger issue is that in an effort to transition him from pitching once a week in Japan to American ball, L.A. is pitching Yamamoto once a week in America.

Giants World Series hero Pablo Sandoval has lost some weight and is with the club in hopes of making a comeback at the age of 37. Here is Steven Kennedy’s story about the Panda at the McCovey Chronicles.

Similarly, former Twins slugger Manuel Sano has dropped 57 pounds in the hopes of reviving his career with the Angels. Find Sam Blum’s piece at the Athletic here.

I’ll just add that I have taken the advice I pointed in Max Muncy’s direction last year and am at a 20-year low of 175 pounds, down 40 from my personal best. Uh, worst. And I’m not stopping there.

Baseball Photos of the Week:

Andy Pages, who wears uniform number 44 in the minors and will make a great number 44 in with the big club one day. Perhaps in 2024.

Willie Davis.

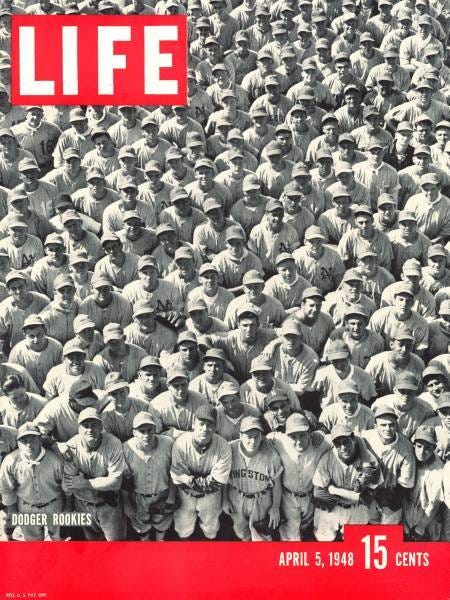

Life Magazine covers the Dodgers at Spring Training, Vero Beach, Florida, 1948.

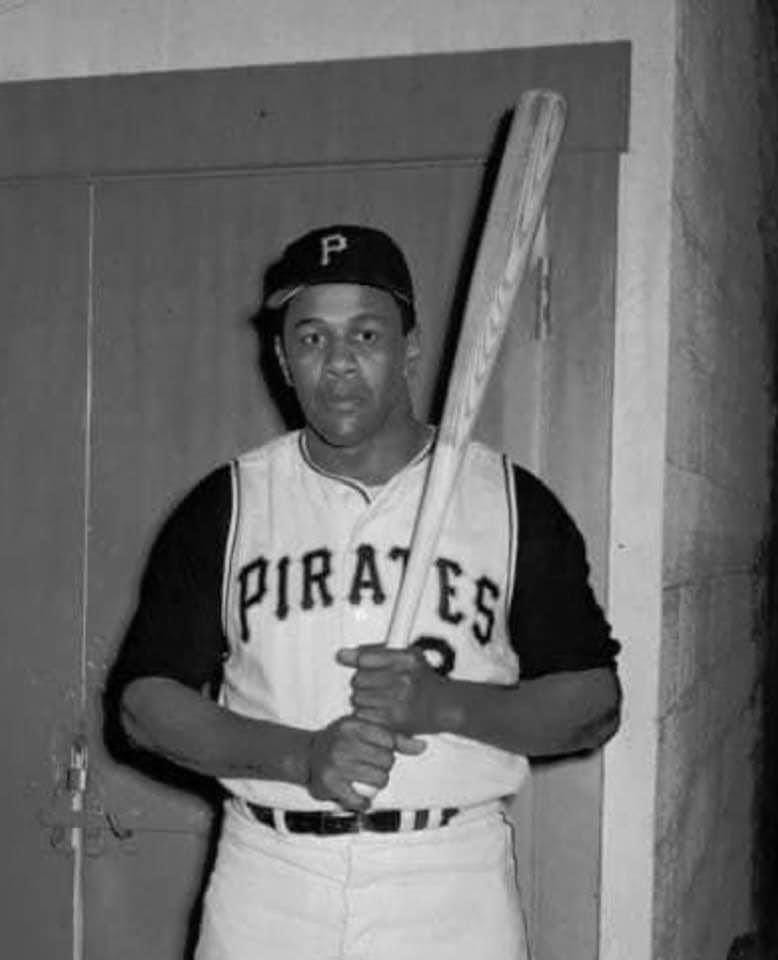

Willie Stargell.

The Dodgers longtime concessioner, Danny Goodman. Read about him here and here.

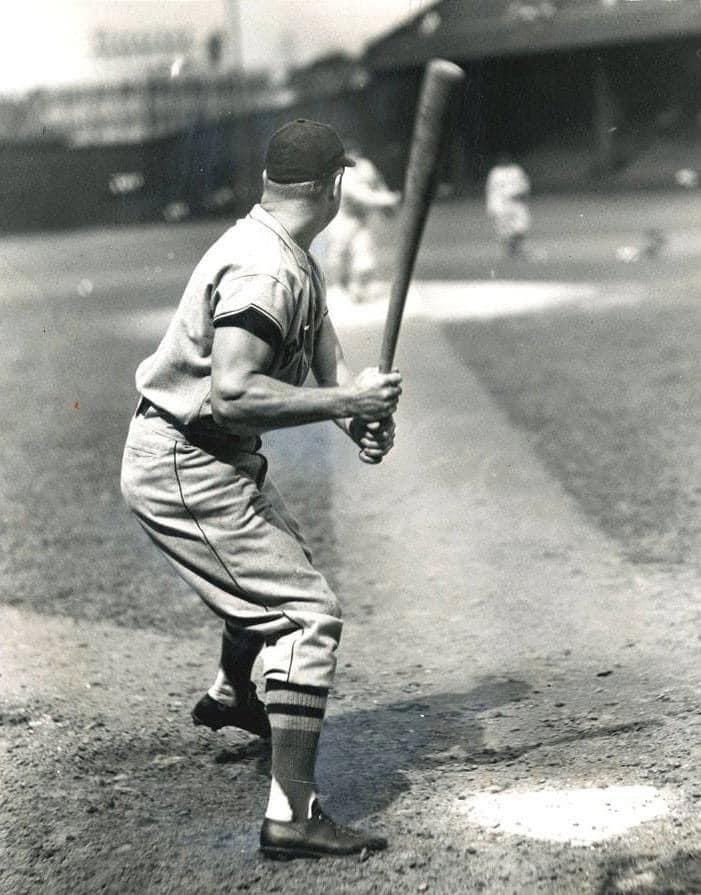

Jimmie Foxx.

The late Richard Lewis.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.