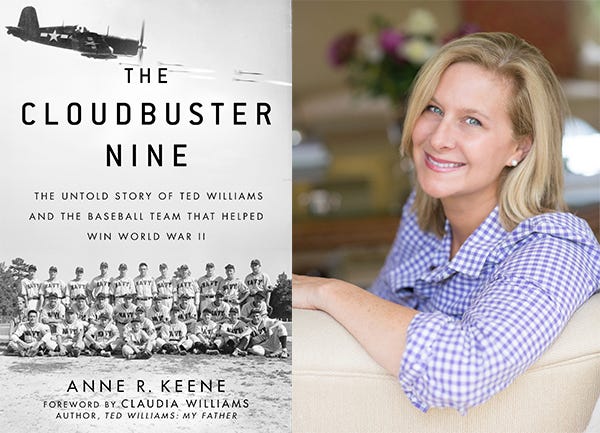

Book Excerpt: The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win World War II

Chapter 19: Walking Billboards for baseball and That Ain’t All

My goodness, what a beautiful book. In its research, in its history and its expressed connection between the team batboy and his author-daughter, “The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win World War II,” by Anne Keene (Simon & Schuster, 2018, Hardcover $26.99, Paperback $16.19), is a fascinating book.

As you might expect, everything having to do with Ted Williams is fascinating. The specifics about his Navy baseball teammates, their military training and the organization of this particular element of preparation for war are fascinating. The appendix, which gives a rundown with photos of the major leaguers who trained at Chapel Hill, including Lt. Charles Gehringer, Lt. Charles Gelbert, Lt. Joe Gonzalez, Cadet Johnny Sain, Lt. Ray Scarborough, Lt. Hal Schumacher, Lt. Ray Stoviak and Cadet Williams, is a must-read. I even got a kick out of the index.

I excerpt I have chosen from “Part VI—PLAYING BASEBALL MILITARY STYLE," is Chapter 19, “Walking Billboards for baseball and That Ain’t All,” with the footnotes omitted, and begins here:

Ivan Fleser recollected that Pre-Flight was the most difficult phase of his aviation training because the pressure was always on: “Everything had to be done their way. You always had to be ready to go emotionally and physically.” Yet he looked forward to getting up every morning because he never knew what to expect, even on the baseball field. He described how the baseball team trained for battle, recalling that there was surprisingly little coaching for technique. He also recalled that there were photographers milling around the base but it was not evident that they may have been looking for angles to show how differently the players trained.

“There was no traditional practice sliding into the bases at Pre- Flight. No coaching for skills. They geared us up for speed, reflexes, and power, and quick and accurate decisions. We were building muscle mass for combat,” he said. Sure enough, when I examined the Pre-Flight photographs, the varsity baseball players were pictured diving headfirst into bases—kicking up a storm of dust. The swan dive was a recipe for bruises and gravel in the palms, but rest assured, it was a good way to practice an emergency dive out of a flaming plane.

“Pesky, who looked more like a football player than a shortstop, could run those bases like a missile,” said 92-year-old Bruce Martindale, a Chapel Hill native who worked as an equipment manager for the Cloudbusters baseball team. Martindale described himself as a skinny teenage boy when he managed bats, balls, and other equipment at Woollen Gym: “I barely weighed 90 pounds and the players laughed at me, saying the bags were bigger than I was.” Bruce saw players hurling baseballs like grenades, but it was the inclusive spirit that grabbed him. He came to know all of the players by name, and they knew his, too. The cadets carried themselves like officers, and he watched them come in and out of the locker room every day, beaten up and soaked in sweat but smiling. “They were always friendly, very respectful to everyone who worked on base, even the scrawny kid handing out equipment from cages,” he said with a chuckle.

Bruce attended all of the home baseball games at Emerson Field and saw Ted knock out “many a window at Lenoir Hall.” There were unconventional sports at Pre-Flight, too, like the caber toss, a sport of Scottish lumberjacks; rugby; and pushball, which was played in Great Britain. Bruce blew up the giant rubber pushball and carried it on a pickup truck to Fetzer Field. He told me he’d never seen anything like it when all 22 players went at the ball to push it over the goal line.

The PR Machine

There were many who left fingerprints on the Pre-Flight publicity campaign. One of those people was William D. Carmichael, who’d made a pile of money on Wall Street and had raised millions for the university through the state legislature, gaining support from the captains of state industry, foundations, and influential families.

One of his disciples was Kidd Brewer, an officer who was too old to become a fighter pilot, so he requested a desk job in a North Carolina spot where the “fighting was the thickest.”

Long before Kidd ended up in the psychiatric ward and the state penitentiary for bidrigging, he was the Pied Piper of the Navy press office. With the help of his editors, Leonard Eiserer and Orville Campbell, Kidd built a crack team of photographers and artists who churned out cartoons, branding Pre-Flight cadets as the Supermen of the war. He was also a charming entertainer who held court with the most influential journalists of his era, and he viciously protected of star cadets like Ted Williams.

In an official Navy portrait, Lieutenant Kidd Brewer stands on the bleachers of Kenan Stadium with his hands on his hips. He is directing a cameraman aiming a motion picture newsreel camera at the football field like a machine gun. Kidd went about his job as the Pre-Flight publicist just like he played football at Duke, having fun and taking in every single play.

In her mid-80s, Kidd’s daughter, Betty Brewer Pettersen, was described by her cousin, Benjamin Kidd Brewer, as spirited, and prone to strong-minded opinions. When I met Betty at a Mexican restaurant with fluorescent murals near her home in Louisburg, North Carolina, she was soft-spoken with a quiet, demure laugh. Like most of the offspring of the Pre-Flight luminaries, she was mystified by her father’s stealthy history at the Pre-Flight school. During the war, Betty lived with her mother in Florida during the winter, spending summers on the Navy base, where her father bought her a little brown pony named Tony. She was about ten years old when her father and stepmother moved to 10 Oakwood Drive in 1942, two miles south of campus near the future site of Finley Golf Course. Neighbors included a host of athletes, including Ray Stoviak, an outfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies; and Lieutenant Alexander McLeigh, a hand-to-hand combat instructor, who lived down the road.

Before I met Betty, she offered to give me a box of old letters written by her father when he was stationed in the Pacific and pictures from his years in the Navy that no one wanted. She had considered throwing them away after a recent move but felt the timing of my call was providential.

In person, Betty bore a strong resemblance to her father; she was fair-skinned with sloping blue eyes, and a gentle, warm smile. Though she never said a word about her own athletic pursuits, Betty ranked among the nation’s fastest race walkers in her 50s, carrying on her father’s genetics. Betty said her father was a wonderful man who made a few enemies after dustups with politicians, but he was “nice to everybody.” At least he tried to be.

“My father was good to me. He embarrassed the life out of me, always landing in the newspaper for doing something crazy,” she said with a quiet laugh. “Once he drove from Raleigh to Winston- Salem in a Santa Claus costume, waving at people on the road,” she said, explaining that he intended to shower people with attention “to lift their spirits.”

As we became acquainted, I sifted through the materials in the box, which proved to be a goldmine of information, hinting toward her father’s never-give-up Pre-Flight attitude. As a toddler, Kidd was pictured in a ragged gown, barefooted and tow-headed, between two calves on the dairy farm in Cloverdale, North Carolina. There were long emotional letters written to her grandparents from the South Pacific, where Kidd thanks them for teaching him to “hang on like a bulldog to a man’s pants” and to learn from the rough rides that follow.

Rare images showed Kidd at the height of his athleticism, testing his strength against a player lassoed with a rope on the Duke University football field. Hundreds of news clippings shed light on Brewer’s famous eccentricities: the mansion on Kidd’s Hill overlooking a Raleigh shopping mall where his influence-peddling for urban sprawl began, the garage stocked with yellow Jaguars and electric-red Cadillac Eldorado convertibles, the trapeze hanging from his living-room ceiling, and the Look magazine spreads featuring Kidd’s adjoining indoor-outdoor swimming pool where he hosted 1920s-theme bathing parties with politicians and Hollywood stars. There were stories about Kidd’s campaign against the judge who put him in jail, and his adventures driving around the state seeking votes on a bright-yellow road paver with whitewall tires. Though many of Kidd’s publicity stunts were outrageous, they tracked perfectly with the campaigns he led to call attention to the Pre-Flight story.

In mid-March of 1943, the Public Information Office and the Cloudbuster newspaper moved to a new building known as Navy Hall. The office resembled a country club with cypress-paneled walls, fireplaces, and gaming tables. The Navy invited bow-tied reporters from the trolley-and-telegram news era to relax in the swanky club chairs and soft leather couches like gentlemen. These historic gatherings merited stories of their own, where sportswriter Grantland Rice was photographed on the couch with reporters, wearing two-toned oxford loafers and a suit before they set out on a behind-the-scenes tour of the base in 1942.

These masters of the Golden Age of Sports, who penned such phrases as “It’s not that you won or lost—but how you played the Game,” nailed the essence of the Pre-Flight culture. With their clever wordsmithing and gentlemanly vision, the story about this rare training culture was told in newsprint, film, and radio from Tobacco Road to the Pacific.

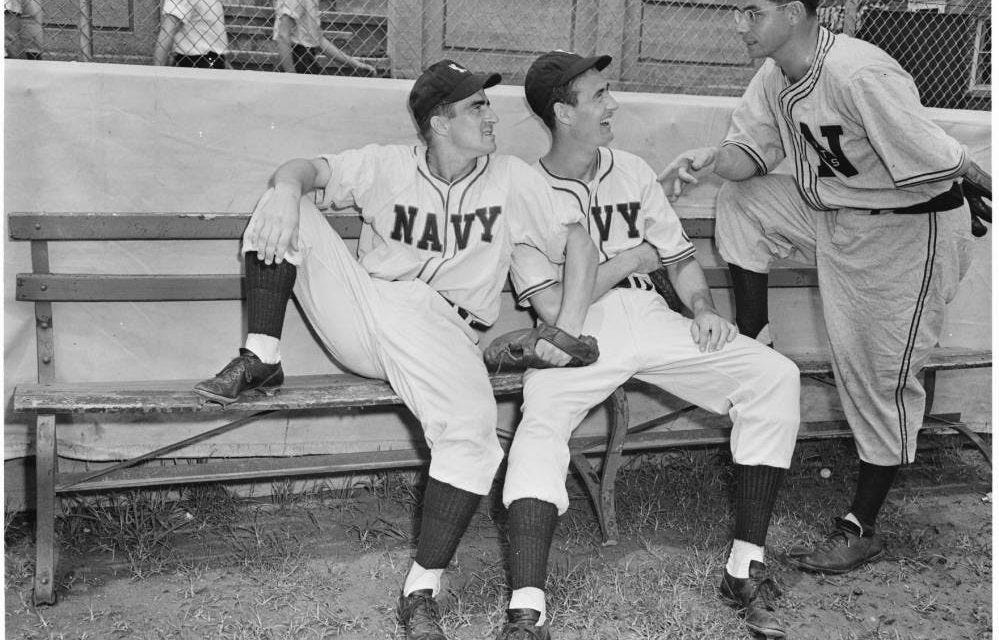

In an age of concentration camps, burned-out cities, and POW confinement, the Navy’s press office pounded the media with uplifting pitches to divert attention from the horrors of war. Kidd’s clubby gatherings in the Navy Hall parlor and his truckloads of press kits paid off handsomely when Ted Williams’s lean image caught readers’ eyes in unexpected places like boxing rings and football fields. Johnny Pesky, who could not swim, grabbed the media’s attention when he paddled like a dog to keep his head above water in the pool.

Pesky, who had gotten his start on a team in nearby Rocky Mount, North Carolina, was trailed by a publicist who captured a typical day in the life of a cadet. With his moonbeam smile, Johnny was pictured happily making his bed, whistling while he combed his hair, and looking a little more serious when he crammed for exams. Like half of the cadets, the rookie shortstop who grew up on the Pacific Coast sunk to the bottom of the pool when he shipped into Chapel Hill. Six weeks into training, Johnny was tumbling off a 35-foot diving platform in full gear cradling a rifle, and doing a cannonball into pools lit with gasoline fires.

Through it all, cadets were playing some grand extra-inning baseball, inspiring UP to write the dream headline: “Johnny Pesky Still Playing Ball, But B’lieve Me, Mister, That Ain’t All.” In the feature, Johnny gave fans an unvarnished view of his new life, noting that being able to field a baseball had not granted him any privileges—it was up at dawn, train all day, hit the road to trim the Durham Bulls, back on base at 11:30 that night. The next morning, he was up again with the roosters at 5:30, took an exam in class at 7:10, dug ditches in labor battalion from 9:30 until 11:30, went to class and swam until 5:30, studying that night for an exam the next day, after finishing up the day with a 14-mile hike.

Piece of cake, right?

To capture the base’s spirit on canvas, the publicity office invited one of New York’s most celebrated artists to Chapel Hill. Long before Don Freeman charmed millions of readers with his classic children’s book about Corduroy the bear, he was a New York Times illustrator, earning high praises for his portraits capturing the human story from the subways of New York City to the heights of theaters on Broadway. He sketched the faces of apple sellers, beggars, showgirls, and drunkards down on their luck, shifting to pilot trainees and coaches who defined an American Gothic image of wartime sports.

That summer, Freeman spent a week on campus, camping out under an umbrella with an easel to capture what people were calling a “training miracle” for national magazines. Though he had documented some of the most graphic scenes of humanity, Freeman was astounded by Pre-Flight training. “The public has no idea of the work involved in training Navy fliers,” he told a military reporter. “My reasons for coming is to tell the world in pictures what cadets go through,” he said. “If I am able to catch their spirit in my artwork, I’ll do just that.”

When Freeman headed back to New York, he left behind charcoal sketches of boxing matches and colorful paintings of cadets dangling from ropes like acrobats and leaving base on buses. With a touch of artistry, a new breed of superhero came to life on paper and canvas.

Star Treatment

My father believed in superheroes—at least he wanted to.

In his view, superheroes came in the form of baseball players. Unlike millions of other kids who worshipped professional athletes, he did not just see his idols’ faces on trading cards or from a distance in the stands, he saw them up close and personal, and the Navy was there to capture it with a camera.

In one of the most recognizable portraits of Ted with kids during the war, Williams played catch with my father and showed him how to grip a bat. Johnny Pesky taught him how to stand at the plate, and they shared their fears about their return to baseball after the war.

As tough as he was, Ted confided that he wanted to see the end of the war. Like everyone else, he was sick and tired of the training grind, and he missed a good old-fashioned home-cooked meal. But most of all, he really hated riding in the humming belly of the bus, and he could not wait to get the heck out of “Chapel Hole.”

As an only child seeking approval, my father viewed Ted and Johnny like protective big brothers. It is likely that they saw something he needed, too. The Red Sox duo came to his house on Vance Street, where Ted ambled around the den, practicing his swing, throwing left-handed jabs he was perfecting in the Pre-Flight boxing ring. They would have noticed the spit-shine military order, the strict parents, the henpecked commander, and they may have sensed that my father was a bit of a menace.

My father described Pesky as a feisty, fidgety guy with a nervous laugh who walked fast. His best friend Williams was cooler, contained, and extremely kind. The two Red Sox players took my dad to the Scuttlebutt snack bar after practice for lemon custard ice cream, “Ted’s favorite,” he always claimed. When they took him to the movies on Franklin Street, Ted called him not by his name, but as a “little son of a bitch.” At the movies, they would sit my father in the front row with a bottle of Coke and popcorn while they went to the back of the theater with their dates. In Dad’s words, Ted said, very sternly, pointing his finger at his face, “Don’t you dare come back here— don’t even think about looking back, you little son of a bitch . . . not even if you have to go to the bathroom . . . you stay put.”

Sportswriters would credit Williams for his ability to make people feel special. Pesky said of his teammate that it was “like there was a star on top of his head, pulling everyone toward him like a beacon and letting everyone around him know that he was different, and that he was special in some marvelous way, and that we were that much more special because we had played with him.”

Williams certainly made my father feel like a star, and he was known to tell rookies, “If you want to see the greatest hitter in the world, just look in the mirror.” Ted encouraged kids to visualize success just as he did as a boy, when there was no one there to guide him. He told my dad to block out the distractions and ignore the people who criticized his abilities. He told him to show up early, and be the last to leave the field. He told him to watch the pitcher and to study his swing in batting practice, and my father saw Ted’s formula for perfection unfold with his own two eyes when the Splendid Splinter rocketed the ball over campus rooftops like a catapult on a carrier.

As I broadened my search from players to others who were in the dugout with the team, I came across another living mascot who had an identical role as my father at the Iowa Pre-Flight base. This man, who grew up to become an admiral, was the protégé of Ted Williams’s most famous wingman in Korea.

Admiral Jerry Holland, the Other BatBoy

The first time I spoke with Rear Admiral Jerry Holland, he confessed that he never told his seven children or his grandchildren stories about his childhood mascot days at the Iowa Pre-Flight base because they’d heard enough of the “old Navy stories.” When he was a kid growing up at 325 Melrose Court, down the street from the University of Iowa campus, Jerry’s parents were civilians with no connection to the military. In his words, Jerry’s father was a pacifist. When the base opened in early 1942, eight-year-old Jerry fell in line with cadets marching down Melrose because “it looked like fun.” He was followed by a scraggly stray spaniel named Blackie Black Bottom, who was also adopted as a base mascot.

One of the cadets marching down the street was a strawberry-blond, freckle-faced Ohioan named John Glenn, who took Jerry under his wing and helped him land the job as batboy and base mascot. Glenn went after the opportunity to fly combat missions as soon as he was eligible, entering the first Pre-Flight class at the Iowa station in May 1942.

After the Navy bought Jerry a cut-down khaki uniform and service-dress blues, it was John Glenn who gave Jerry the nickname that stuck for life, “Admiral.” Pictures in Glenn’s scrapbook, taken by Jerry’s mother, show the two in matching uniforms, standing beside a large boxwood by the side of their house.

For decades, the Iowa City newspaper followed Jerry’s career as a hometown success story. He graduated from Annapolis, going on to became an admiral and a submarine commander in the Navy. Jerry also earned a Master’s degree from Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and writes on national defense issues with particular emphasis on command and control and communications, nuclear weapons policy, and submarine warfare. As a naval historian and vice president of the Naval Historical Foundation, he edited The Navy, a comprehensive chronology of the history of the U.S. Navy.

When I interviewed Holland, he showed little nostalgia for his years as the base mascot, feeling that he had done more significant things in his life.

As we talked, and I asked more questions, Admiral Jerry cautiously opened up. When I asked if the base had a band, he paused, without an answer. Then, the photographic memory went to work, filing through bands he had served with, and he said, “Hmmm . . . yes, they had a band. I see them now . . . I believe there were about 18 to 24 members.” Like the Chapel Hill band, the Iowa band only played at football games, not baseball games, and that memory took us back to the University of Iowa in the spring of 1942.

Early in the war, he explained, the armed services were recruiting everyone they could get their hands on, especially natural athletes and professional sports stars, who were grabbed off by Army Air Corps and Navy aviation branches. Recruiters wanted men who were already in tip-top physical shape. “If you start with a guy in good shape, training does not take as long,” he said. Jerry explained that some commands tried to keep the best players on base, sometimes honestly, sometimes nefariously—and commands battled each other on sports fields. As the pilot preparation line backed up with more cadets than the Navy could train, the great athletes and coaches stayed on bases.

Notable coaches on the Iowa campus included Lieutenant Colonel Larry Snyder, Ohio State track coach, who developed the Olympic track and field star Jesse Owens. Snyder oversaw track meets and the grueling 550-yard obstacle course run by every cadet each week with jagged log fences to hurdle, chutes to crawl though, water holes and muddy canyons to cross over hand-over-hand on ropes, 11-foot walls to climb without help, and steep hills to attack at full speed. While the record was set by a national A.A.U. half-mile champion, it was broken several times over by cadets in training, proving that there is always someone in the wings who is faster and stronger.

Other coaches included Ensign Newt Loken of Minnesota, national all-around gymnastics champion, and a dozen or so All-American football players at any given time.

Coached by Lieutenant Commander Bernie Bierman, who was already white-headed by 1942, the Iowa Seahawks football team would go on to be listed by the Associated Press in 2017 as one of the top 100 college football teams of all time. During the war, the stadium was often packed with 16,000 fans for three short seasons as Bierman and Missouri’s Don Faurot, who invented the split-T formation, turned the Seahawks, whose moniker derived from a wartime marriage between the Navy and the Hawkeye State, into a national sensation.

Like my dad, Jerry served as batboy for the Seahawks baseball team, smiling for the camera as he lugged bats in a spiffy team uniform. Jerry rode on the team bus to games, where the Seahawks played local, rather weak “Three-I League” squads in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. He had an official job of riding in the back of the bus to supervise the dispensing of bubble gum to baseball players. Jerry felt like the higher-ups did not see it as a legal operation, so they banned “the kid” from traveling on the road with the team.

For several years, with Blackie the mutt in tow, Jerry was a paperboy who delivered the Spindrift base newspaper to officers around the station. The paper’s name was inspired by the stinging spray that whips across ships at sea. At the Spindrift press office, he befriended a talented young illustrator from Indiana by the name of Theodore “Ted” Drake. Jerry remembered Drake as a pleasant, outgoing editor who wrote the “Who’s Who in the Crew” blurb and pioneered the “Woo-Hoo in The Crew” column when the female WAVES arrived.

After the war, Drake sprinkled the gritty Pre-Flight fairy dust on his commercial work for Wilson Sporting Goods at its headquarters in Chicago. He drew Wilson’s professional athletes who had trained at Pre-Flight, such as Jim Crowley and Otto Graham from Northwestern and, of course, his good friend Ted Williams. Other athletes who posed for his sketches included Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Babe Didrikson, and Chicago White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox. Years after Drake left the Pre-Flight campus, that fighting athletic spirit was channeled into other mascots. For $50, Drake designed Notre Dame’s bearded Fighting Irish leprechaun in 1964, which was later copyrighted by the university. Possibly drawing on inspiration of Pre-Flight fliers’ bullish, never-give-up attitude, he drew the logo for the NBA’s Chicago Bulls in 1966.

Another testament to the Pre-Flight spirt is displayed at the media entrance of Notre Dame Stadium, where Jim Crowley is portrayed in Drake’s Four Horsemen painting.

Though Jerry downplayed his childhood job, and he certainly did not “roll in” the memory, I could not help but wonder how men like astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn, who had shaped the world, had influenced him at an early age.

When I examined Glenn’s Pre-Flight records, personality traits began to emerge. After passing through Pre-Flight School, he became a recruiter on the three-member flight board to determine if candidates had, in the words of a 1942 reporter, the right “stuff” to become an officer and a pilot. Recruiters looked for four things: education, exemplary coordination, the spirit of leadership, and a familiarity with aviation. When an Esquire reporter shadowed an interview, Glenn dug right into athletics, saying, “You know, the first thing they do is throw you a football suit . . . you understand the hazards, right?” Officers listened to cues on how potential fliers treated women. Knowing that the country was fighting a dirty, unethical war, recruiters looked for intangibles like a quiet confidence and courage. Officers had to know that candidates would not hesitate to kill the enemy if given the chance. If candidates did not possess the grit to do their jobs, they were dropped from the list.

Like Glenn, some of the famous Pre-Flight cadets did not earn the highest scores in the classroom. They did, however, possess an unusually high aptitude for perseverance, endurance, and loyalty— traits that make or break a person in the struggles of life. Getting beaten to a pulp did not faze them; many had a sense of humor and were incredibly resilient, learning to bend instead of break when they were put in stressful situations.

More than anything, the dominant characteristic that determined success as a flier, be it a baseball star, an astronaut, or a future president, was the tolerance for failure.

In fact, the expectation of failure is what drove them.

About the author:

Anne R. Keene is an Austin, Texas-based writer who focuses on narrative nonfiction. A graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Journalism, she began her professional career working as a speechwriter on Capitol Hill. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Dallas Morning News, the Raleigh News & Observer, National Geographic Books and a variety of sports publications. Passionate about historic preservation and athletics, Anne is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research and speaks around the country at ballparks, museums and literary groups about WWII and naval aviation baseball. Website: annerkeene.com.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.