Book Excerpt: The Cup of Coffee Club: 11 Players and Their Brush with Baseball History

Larry Yount: September 15, 1971.

From Baseball Reference: “A player with a ‘cup of coffee’ is one who has played only one game in the majors as either a pitcher or a batter.” The website provides the names of all men who share the distinction. Since the list pops up alphabetically, Larry Yount’s name is displayed 1525th and 725th among batters and pitchers, respectively; sixth from the bottom. Which may tell you something about the chapter you are about to read.

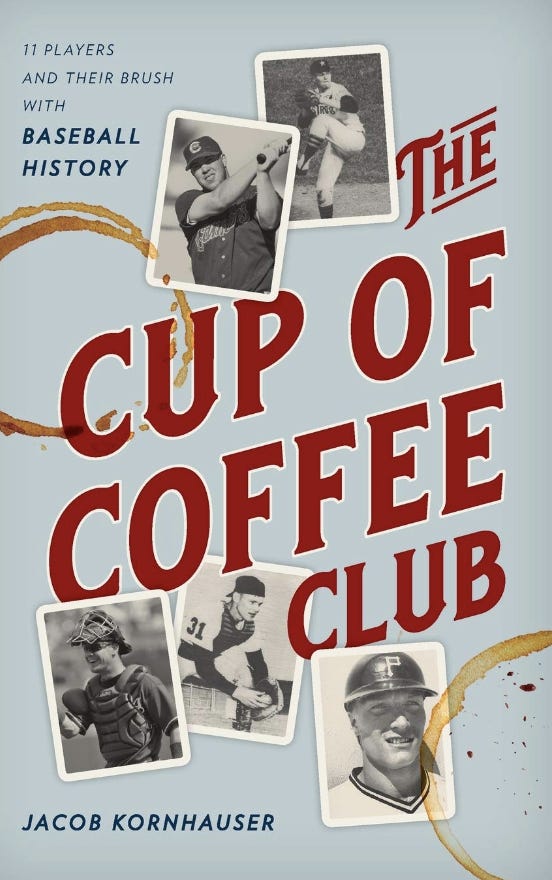

With number 19 in our book excerpt series, I am pleased to recommend an entire volume of cup-of-coffee stories. It is “The Cup of Coffee Club: 11 Players and Their Brush with Baseball History,” by Jacob Kornhauser, (Rowman & Littlefield, originally published in 2020, some to be released in paperback, $18.00; Kindle, $16.99).

Since there no Dodgers featured in the book, I thought I’d share the next best thing: a story about a local boy named Larry Yount, a graduate of Taft High School in Woodland Hills and the older brother of Hall of Famer, Robin Yount. Chapter 3, heartbreaking from a baseball perspective but far from sad, is excerpted below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 3: Larry Yount

September 15, 1971

Walking down Ventura Boulevard, a young Larry Yount’s eyes darted around, catching the surrounding pageantry. Baseball was in the air. It was Opening Day. In the late 1950s, Little League still meant something and the league’s opening day was something worth throwing a parade over. Parades and other baseball-related events introduced Yount to the game. It was through the excitement such events generated that his love for baseball was born.

He listened to Dodgers games on the radio. They were the new team in town, fresh off fulfilling their own manifest destiny, and a young broadcaster named Vin Scully was in the first of his seven decades as the beloved voice of the franchise.

“Listening to the Dodgers on the radio with Vin Scully broadcasting, that was a big deal,” Yount said.

His early baseball memories continued to foster a love for the game. Yount’s grandfather, an avid Cincinnati Reds fan, took him to a double header at Crosley Field in his childhood.

“We got there in time for batting practice,” Yount said. “We were along the rail and they were taking batting practice. Johnny Edwards broke his bat and waved me onto the field to come get it.” It was the first time someone would call him onto a major-league field.

That bat became one of Yount’s most prized possessions. As the years went by, he turned passion into promise as he played his way onto an elite Pony League team. His team reached the Pony League World Series in 1963 when he was 13 years old.

“Some way, somehow, I figured out how to throw a breaking ball,” Yount said. “I was really good at it. I was the smallest guy on the team and a relief pitcher. All I did was come in and throw curveballs.” Most boys who went through Little League remember the first kid who figured out how to throw junk. For a time, he became virtually unhittable.

His younger brother, Robin, eight years old at the time, was the team’s batboy.

Larry and Robin were raised by intellectual, unathletic parents, Marion and Phil. It was hardly the household you’d expect two future professional ballplayers to come from. Phil was literally a rocket scientist. The move to California was precipitated by a job he took with Rocketdyne where he was the head of quality control, in charge of building rocket engines.

“It’s not typical for two baseball players to come out of that situation,” Larry Yount said.

Throwing strikes isn’t rocket science, but for some pitchers, throwing strikes with breaking balls is just as hard. That was never the case for Yount, which helped to separate him from many of his contemporaries. With the help of his right arm, his Pony League team finished second in the country that season, losing in the championship. Through a tournament blind draw, he was selected to throw out the first pitch at a Dodgers game. He wouldn’t be throwing out the first pitch of just any Dodgers game. The game he got to throw the first pitch at? Game Five of the 1963 World Series.

This set of cosmic events, that random selection and its aftermath, served as cruel foreshadowing for how his professional career would play out. Yount would not get to throw out that pitch, because the series never reached a fifth game.

“I can remember distinctly, sitting in my car, listening to the fourth game of the World Series when the Dodgers won four straight,” Yount said. “I remember how crushed I was that I wasn’t going to get to do something pretty unbelievable.”

The Dodgers swept the Yankees in the ’63 fall classic, and Yount was despondent. Not getting to throw out that first pitch still stands out as his most distinct baseball memory. Luckily for Yount, someone with the Dodgers was looking out for him.

“The Dodgers, to their credit, had somebody there who had enough sense to understand what a crushing blow that was to a 13-year-old boy who thought he was going to throw out the ball,” Yount said, “so, they invited me to throw out the Opening Day ball in 1964.” Yount would later see that this concern for fairness did not extend to professional ballplayers, but for now it appeared that the game he loved did, indeed, love him back.

Yount ended up throwing out the first pitch of the 1964 season as the Dodgers were celebrated as the defending world champions. He threw the ball to Johnny Roseboro, a moment he said he will never forget. Afterward, he sat in the dugout with Jeff Torborg and chatted with him about the game they shared a passion for. The likes of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale passed through the dugout as their conversation went on.

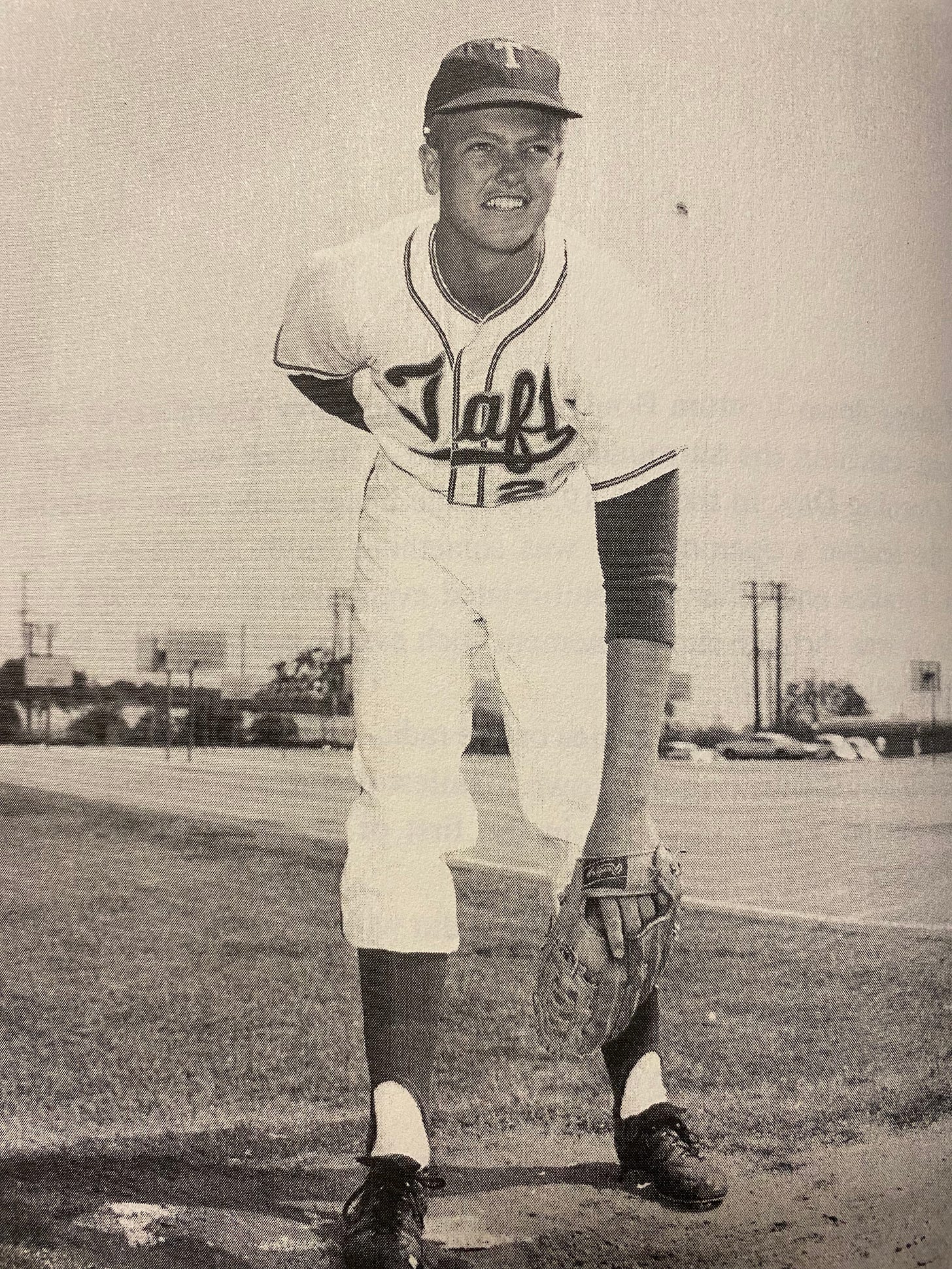

It was a moment that would motivate the teenager to pursue his dream. For Yount, that dream was pitching in the major leagues. On a perfect April afternoon in LA, his desire was reaffirmed. Yount shed the label of a small, specialty relief pitcher by his junior year of high school. He shot up and developed a deeper arsenal of pitches. With a bigger frame, he was throwing harder, adding a fastball to his already polished off-speed attack.

Pitching for Taft High School in Woodland Hills, California, Yount caught the eyes of more than a few scouts. When he was taken by the Houston Astros in the fifth round of the 1968 MLB draft, he was too young and cocky to recognize the moment’s importance.

“I didn’t think anything about it. I thought it made sense. I thought I was pretty good, I guess,” Yount said. “When I got drafted, I actually went out of high school to Triple-A, which was not typical even back then. I didn’t know any better.”

Yount, just 18 years old when the Astros selected him, was put on the fast track. He spent his first several spring trainings in big-league camp. Ignorance was bliss as Yount worked his way through the Houston system. The naïveté of his youth served him well.

“It certainly was an asset,” Yount said. “If you never know the rest of them are chasing you, you don’t know who might be gaining on you.”

In his first spring training appearance, Yount looked down at the signs from his catcher as he prepared to throw his first professional pitch. Staring back at him was Johnny Edwards, the former Reds catcher who had waved him onto the field when he was a child. Yount recalls a brief conversation between the two before the game. “Johnny, I was a little kid, remember when you gave me that bat?” Yount asked.

“Get out of here, kid,” Edwards said, or something along those lines as Yount remembered. Welcome to the big leagues.

By his second year in professional baseball, it was clear he had the capability to pitch in the major leagues on a regular basis. After getting the growing pains out of the way, spread between Single-A and Triple-A in 1968, Yount broke out in 1969. The Astros had pumped the brakes on him, which helped his development. He went a combined 11–6 with a 2.27 ERA split between winter rookie ball and Single-A in 1969, pitching a few levels below where he had begun his professional career.

The following season, he moved up to Double-A. With the Columbus Astros, he went 12–8 with a 2.84 ERA in 26 starts and hurled 11 complete games. It was the next step toward the big leagues as Yount started toward a more traditional route to the majors. By then, he was moving up one level of competition at a time.

He started 1971 in Triple-A Oklahoma City. He went 5–8 with a 4.86 ERA, a step below what he had done at the Double-A level. This time, though, he was going against harder competition. During the summer of 1973, Yount’s younger brother, Robin, now a budding high school star, spent time with Larry and his Denver Bears teammates.

“He would come out for a week or two where we were taking batting practice,” Yount said. “That helped him realize he could play with the people on the field.”

When he arrived home from hitting against Triple-A pitchers as a teenager, Robin reportedly got back to baseball practice as excited as ever. He told his high school coach, “I hit guys in Triple-A. They tried to get me out and I still hit them. . . . I think I’m going to have a pretty good year.”

One could loosely characterize his next two decades as “pretty good.” Since he was busy forging his professional baseball career, Larry did not get to see Robin’s ascent in the sport. However, gestures like his invitation to Robin to join the team during the summer showed how invested Larry was in his younger brother’s future. He played a big role in his development as Robin, too, rose through the ranks young, eventually making his major-league debut at 18.

“I don’t think we knew he was going to be this great baseball player until really late in high school,” Larry said. “I was gone playing professional baseball at that point. I don’t think I ever saw him play in a high school game.”

When Oklahoma City’s season ended in 1971, Yount was called up to the Astros. Before he could join Houston, he was required to attend an army reserve meeting.

Spurred on by the Vietnam War, Yount and many others were in the army reserve at the time, and as part of his duties, he had a mandatory meeting, lasting several days. It just happened to fall in the time when his Oklahoma City season ended and he got the call from Houston.

Without a mitt or a ball, Yount was unable to throw and keep his arm loose during the several days he was away. Throughout his career, any rustiness he felt in his arm was caused by underuse, not overuse. Eventually, Yount had fulfilled his obligation and was, at last, set to join the Astros.

“Somehow, I ended up in Atlanta,” Yount said. “I’m still not sure how I got there.”

He didn’t get there. Maybe Yount has tried to block it out or the baseball memories have melted together over the years, but the Astros weren’t playing in Atlanta. Yes, they were playing the Braves, but the series was at the Astrodome in Houston. On September 15, 1971, neither the Astros nor Braves were in contention for a playoff spot. There were only 6,500 fans on hand for the game. They all were buzzing when, in the top of the fifth inning, Hank Aaron clubbed career home run number 636. It gave him 1,954 career RBIs, tying him with Ty Cobb for third on the all-time list.

Yount doesn’t have a strong recollection of this or much else that went on during the game. He had a laser focus out in the bullpen, hoping his first chance to pitch in a big-league game would come.

“I didn’t think very much,” Yount said. “I was paying attention to what I was doing, so I really didn’t see what was going on. Having said that, I knew my arm was getting pretty sore.”

With his team trailing 4–1 late, Yount was told he would come in to pitch in the top of the ninth inning. He started to warm up. Immediately, he knew something was wrong. He willed his arm to get better with each subsequent warm-up pitch, but the pain wouldn’t go away.

“I hoped it would feel better when I got to the mound,” Yount said. “There was a lot of hope it would happen or I wouldn’t have gone in.”

Someone with his level of discomfort would never be thrust into a game in the modern day. In 1971, though, a 21-year-old trying to prove himself wasn’t going to let anything stand between him and pitching in his first big-league game. He was sure the soreness would go away once the adrenaline started coursing through his veins.

Joe Morgan grounded out to end the home half of the eighth inning. Then, the public address announcer went over the intercom to announce that Larry Yount would be entering the game for the Astros. There it was: Yount was officially in the major-league record books. Yount trotted out to the mound, trying to work the rust out of his arm, rust he is convinced was caused by his weeklong army reserve layoff.

“It was getting progressively worse, so I knew that it wasn’t going to just be a miracle and go away at that point,” Yount said. “I was just hoping, because I wanted to go in. I wanted to be in that game more than anything in the world.”

Due up for the Braves in the ninth were Felix Millan, Ralph Garr, and Hank Aaron. That season, Millan was an all-star. Garr batted .343 in 1971. Aaron was in the midst of giving the Sultan of Swat a run for his money. Yount had his work cut out for him.

“That would have been an interesting way to start a career,” Yount joked.

However, as he got down to his last few warm-up pitches, Yount realized he would be putting his young arm in harm’s way if he tried to pitch. He had a decade or more ahead of him. It was the smart move to make sure he escaped further injury by avoiding putting his arm under the physical pressure required to throw in a major-league game. He made one of the hardest decisions a professional athlete has ever been asked to make. At the time, it was a straightforward one.

“After throwing a couple warm-ups, I thought, ‘If I keep this up and really try to do what I need to do to get somebody out, I could hurt myself,’” Yount recalled. “At 21 years old, generally, you don’t make rational decisions, but I had enough sense not to take the chance.”

Yount pulled himself from the game. He wasn’t physically capable of pitching effectively. Reliever Jim Ray was called in to replace him.

“It’s not an easy thing to do when you’re getting your opportunity, but I did and I came out of the game without throwing any pitches,” Yount said.

Yount didn’t throw a single pitch, but he was credited with a major league appearance. MLB rules state the announced pitcher must start the inning, unless they are removed due to injury. At just 21 years old and 1971.

Ray pitched a scoreless ninth, the Astros scratched across a run in their last time up and lost 4–2. Yount’s sore elbow kept him out of the rest of the 1971 season with the belief he had a very good chance of making the Opening Day roster in 1972. He did have a reasonable beat on a spot in the starting rotation.

After the 1971 season, Yount pitched effectively in the instructional league, his elbow soreness gone within two weeks of his lone MLB “appearance” to that point. He came into spring training the following season and continued to impress. He was competing with two other pitchers, Scipio Spinks and Tom Griffin, for a spot in the Astros’ starting rotation. Spinks and Griffin were out of options; Yount was not. “I made one bad pitch all spring,” Yount recalled to Astros Magazine in 1989. “It was a three-run homer to Willie Davis and it was right when they had to make the decision.”

The Davis homer didn’t help, but cutting Yount from the big-league roster was a business decision. Yount was player no. 26, the final player sent down before the 25-man roster was etched in stone. He was sent back to Oklahoma City. There, he started 3–0, looking as if he’d soon join the Astros rotation for good. Before he had the chance, the wheels fell off.

“I started having some things not go well and I started thinking about, ‘Why am I not throwing strikes? I’ve thrown strikes my whole life,’” Yount remembered pondering. “I managed to figure out, mentally, how to screw up a pretty good thing.”

Accuracy with his breaking ball had been Yount’s calling card since he was in Pony League. Now, it was accuracy that was threatening to derail his promising professional career. Yount pitched in Triple-A in each of his next two seasons, going a combined 8–26 with ERAs of 5.15 and 6.79, respectively.

Sensing his best years were behind him, the Astros traded Yount to the Brewers, the franchise that had just selected his brother, Robin, third overall in the 1973 MLB draft when he was just 17 years old. Larry said the two never crossed paths in spring training. Cuts had already been made by the time Larry arrived. Robin was now 18 and it was his first spring training. He made the big-league club, playing in 107 games his rookie year. Larry didn’t play at all in 1974.

“I was hoping somehow, somebody would tell me something to figure out how to throw strikes,” Yount said. “That didn’t happen. I was always struggling to figure that out. I just couldn’t throw strikes anymore. Once that happens, it’s not easy to correct.”

Yount even went back to Taft High School to talk to his former coach, Ray O’Connor, he told the Los Angeles Times in 1994. His coach recalled him as a somewhat arrogant pitcher during his high school days. When he watched him late in his professional career, he saw a pitcher with the opposite demeanor. He was lost.

The 1975 season was Larry’s final trip around the bases. He had sought out psychological advice, anything that would help him regain his mental edge. Some advice helped; other advice didn’t. At 25 years old, his life was really just beginning. His professional baseball career was

Yount had gotten a real estate license during his season in the instructional league just ending. He went 0–4 with a 5.32 ERA in Single-A and 8–12 with a 4.74 ERA in Double-A in 1975. After the season, he called it quits.

Yount never got back to the big leagues. Moonlight Graham’s career is one someone with Yount’s experience might envy. At least Graham was standing on the field when pitches were thrown. Yount got as close as you can possibly get to reaching the pinnacle of your profession— pitching in a major-league game—without actually getting there. He is quick to point out that his injury and decision to remove himself from the game is not what kept him from having a successful big-league career.

“I don’t think about that moment much, because I had plenty of opportunity afterward,” Yount said. “I certainly don’t look at that as ‘would I have done it differently?’ I wouldn’t have, because after the fact, I was very good and had every opportunity.” Though he said he seldom thinks about it, this sort of clarity hardly comes without some significant time spent reflecting.

Yount is still the only pitcher in major-league history to be credited with an appearance without facing one batter in his career. He is a statistical anomaly, a tragic footnote on the history of the game. Just 25 years old, Yount, without the game he grew up on, now had the rest of his life to look forward to. “I didn’t want to try and raise a family in Los Angeles,” Yount said. “So, we moved to Arizona and I got a real estate license and went to work.”

Yount had gotten his real estate license during his season in the instructional league following his one appearance in 1971. He said he mostly got the license to pass the time. It ended up changing his postbaseball life. After his first few years in Arizona, he decided to learn the business by going out on his own. He learned every part of the business, building an industrial building, shopping center, and office while overseeing building, leasing, financing, and managing. Over his 40 years in the business, he built a multimillion-dollar company, LKY Advisors, LLC. After a lifetime of work, Larry Yount was a success. It wasn’t the success he’d once pictured for himself, but it was a success all his own.

He continued to be involved in baseball through his brother, Robin, who quickly budded into one of the sport’s biggest stars while playing for the Brewers.

“I represented my brother in his contract negotiations, so I was always interacting with Bud [Selig],” Yount said. “Any contract negotiations he had, I was in the middle of them.”

Yount befriended then Brewers owner and future MLB commissioner Bud Selig, and the two are still friends to this day. While Yount wasn’t ultimately the one to deliver a major-league franchise to Phoenix, he did mention the potential expansion location to Selig on several occasions. About a decade after he and several others had made a push in the late 1980s to get an expansion team to Phoenix, the area landed the Diamondbacks in 1998 under the leadership of Jerry Colangelo.

In the lead-up to the Diamondbacks, Yount worked as the president of the Triple-A Phoenix Thunderbirds in the 1990s under team owner Martin Stone, a catalyst for the move of both the NFL’s Cardinals and the MLB’s Diamondbacks to the area.

Yount still throws the ball around from time to time. As he built his real estate business, he saw his children mature, improving upon baseball skills their dad had learned around their age as well.

“It’s certainly fun to throw baseballs to your kids,” Yount said. “There’s nothing more fun than that.”

Even as his kids grew up, he kept trying to figure out what had gone wrong with him mentally during his playing days. As he played baseball with his kids in a more relaxed environment, some answers started coming to him. Of course, by then, too much time had passed.

“I’ll always wonder why I couldn’t figure out how to get back to where I was,” Yount said. “I was lucky enough to throw batting practice afterward to my two boys and slowly, but surely, I began to figure out some of the things I couldn’t figure out, but at that point in time, I was too old.” That sort of clarity paired with productive athletic years is a privilege afforded to a fortunate few.

As Austin and Cody Yount grew up, it was apparent they had the same raw potential their dad did. They would not be like their dad in one respect, and it was through his own experience Larry made sure this was the case.

“The thing Rob and I did not do is get a college education and the thing I was going to be sure of was my kids all did,” Yount said. “At some point in time, you realize no matter how great you are, your career is over and you have to do something else. Having an education is invaluable.”

Austin went to Stanford and was selected in the 12th round of the 2008 MLB draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers, the team his dad had thrown out the first pitch for on Opening Day 44 years prior. He played parts of four seasons in the minor leagues, reaching as far as the High-A Winston-Salem Dash. Cody was picked in the 37th round of the 2013 MLB draft by the Chicago White Sox. After two seasons in rookie ball, he was out of Organized Baseball, not afforded the chance to skip the low levels of the minor leagues like his dad and uncle were.

Robin Yount played 20 years in the big leagues, joining the 3,000-hit club and becoming one of the greatest players in Brewers history. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999. Baseball fans know Robin Yount’s name. Very few know Larry’s. Success in baseball, though, isn’t the only measure of success in life. Larry has lived nearly 50 years without playing baseball competitively and, had he gotten a chance in the majors, he doesn’t think the life he’s grown to love would even resemble what it is today.

“If I had been in the big leagues for any length of time, my whole life would be different,” Yount said. “I probably wouldn’t be married to the same person, I wouldn’t have my kids, I wouldn’t be in the real estate business the way I was. That probably would have been a huge, huge difference in my life, that path change.”

He added, “My life couldn’t have been any better. I overachieved so much. All of that was just a moment in time.”

A moment in time: something Yount got to experience on a major league mound for a few fleeting seconds, never to return to pitch in another big-league game. To get that close and not throw a pitch, it’s hard not to wonder “what if.” Nearly half a century removed from his one moment in the sun, Yount is ecstatic with the way his life has played out. He talks about the things he’s accomplished, his mark on the sport, and the kids he’s raised to love the game, with the excitement of a Little Leaguer, eyes darting side to side, marching in an opening day parade down Ventura Boulevard.

About the author:

Jacob Kornhauser is a die-hard Chicago Cubs fan who grew up 30 miles from Wrigley Field. His passion for baseball led him into sports writing for such publications as Bleacher Report and FanSided, a Sports Illustrated subsidiary. He has covered sports for local television stations in Missouri and Oregon, and his career has led him to work for two sports media giants: ESPN and FOX Sports. He lives in Durham, North Carolina with his wife, Khaki, and dog, Daisy, where he is attending Duke Law School.