Book Excerpt: The Greatest Summer in Baseball History: How the ’73 Season Changed Us Forever

Chapter 12: Rah Rah Rah for Cha Cha

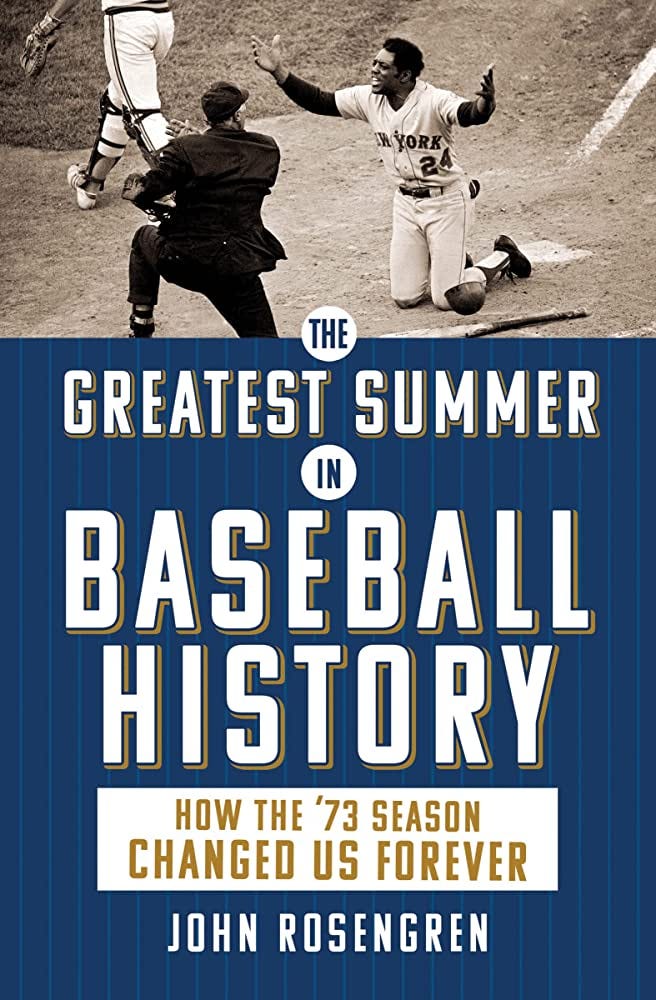

With number 22 in our book excerpt series, I am pleased to present yet another fine work by a prolific author. Originally published in 2008, updated and re-released for the 50-year anniversary, it is “The Greatest Summer in Baseball History: How the ’73 Season Changed Us Forever,” by John Rosengren, (Sourcebooks, $7.99 Kindle, $16.99 Paperback).

First, by way of introduction, are a few words from Mr. Rosengren:

“Today's the day. My new book hits bookstores. ‘The Greatest Summer in Baseball History: How the '73 Season Changed Us Forever’ looks back fifty years at a time when Watergate was unraveling, Roe v. Wade was decided, gasoline was hard to come by, and sport reflected society. George Steinbrenner bought the Yankees and began the infusion of big money into the game, the designated hitter rule was introduced, Hank Aaron chased the career home run mark of the beloved Babe Ruth amidst bigoted resistance, and, in the World Series, Willie Mays passed the torch to Reggie Jackson, the prototype of the modern superstar. That's the story I tell, of a watershed year in the nation and in baseball.”

There is much about the designated hitter in the book, with a chapter called “The Designated Hitter Has His Day” and mentions of the men who filled the role, including Tommy Davis Tony Oliva, Frank Robinson, Deron Johnson, Rico Carty, Jim Ray Hart, Ollie Brown and first but not least, Ron Blomberg.

Orlando Cepeda, who at 37 years of age hit .289/.350/.444 with 20 home runs and 86 RBIs as the Red Sox DH in 1973, is featured prominently. It is with the 1967 National League Most Valuable Player in mind, that I have chosen Chapter 12 to excerpt. It begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 12: Rah Rah Rah for Cha Cha

There may not have been a place on the All-Star team for Orlando Cepeda, but he was playing like an All-Star. His knees, nearly crippled at the start of the season, had grown stronger. He had remained faithful to the conditioning program designed for his knees by the Red Sox trainer, and he had been careful to keep his weight down.1 Most importantly, Cepeda’s swing, which he had claimed was never better when he arrived in Boston, had lived up to his words. His greatest liability and strongest asset won him a place in the hearts of the Fenway crowds and Sox fans throughout New England.

Two weeks after the All-Star Game, Cepeda had the chance to strut his stuff at Royals Stadium. On Wednesday, August 8, Boston’s designated hitter slammed four doubles, tying the major league record. The knees carried him safely into second four times, and the swing drove in six runs in the Red Sox’ 9–4 win. Two days later, back in Boston for a series against the Angels, Cepeda hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the second inning to tie the game. It was his 17th of the season and the 375th of his career. That moved Cepeda to 18th on the all-time list, past Rocky Colavito. Cepeda may not have been challenging Ruth, but he was delighting the fans in one of the Babe’s old haunts.

Two days after that, on a Sunday afternoon at Fenway, Cepeda doubled in the second inning off California’s spitball All-Star Bill Singer, rapped singles in the third, fifth, and sixth innings, then slugged a solo homer to center field in the seventh. His five-for-five performance lifted his average to .302. His 71 RBIs were second best on the team.

The popularity of the designated hitter had grown in American League cities during the course of the season, but nowhere was the DH more popular than in the person of Orlando Cepeda. “A lot of designated hitters have created excitement in the American League this season, but none more than thirty-six-year-old Orlando Cepeda of the Red Sox,” The Sporting News reported.

Others performing the same role for other teams, intimately aware of the pressures inherent in the new position, tipped their hat to Cha Cha’s success. Frank Howard, the Tigers’ DH, said he would pay his way into the ballpark to see Cepeda play.

After his five-for-five performance, Cepeda talked hitting with a group of sportswriters in the Boston clubhouse. He claimed that he was coming into his prime as a hitter but that hitting remained a mystery to him. “I don’t know how to hit,” he said, seemingly defying what they had just witnessed. “Hitting is a personal thing,” he explained. “It is not a science to me the way it was to Ted Williams.”

While he may not have mastered the science like Teddy Ballgame, Cepeda had made an art of hitting. In the series with the Angels, he had hit one ball into the bleachers behind the Red Sox bullpen in right-center and another into the center-field seats. He had also clubbed many over the Green Monster in left. Unlike Aaron, whose home runs knew just one route—the shortest distance to the left-field seats— Cepeda managed to homer to all fields.

Cepeda was baffling opposing pitchers, proving to be a difficult out. The Sporting News offered this scouting report on Boston’s right-handed DH: “He lashes outside pitches to right field, and he pulls inside pitches to left. Some managers now believe the best way to pitch him is inside, but then there is the frightful risk of a fly ball into the chummy nets at Fenway.” Of course, having played in the National League until 1973, Cepeda had the advantage of being an unknown among his AL opponents, but his ability to hit most pitches frustrated their efforts to learn his weaknesses.

Cha Cha also excelled in the clutch, seemingly hitting best with two strikes on him. He preferred not to swing at the first pitch, wanting first to have a look at the pitcher’s stuff. Though that often put him behind in the count, he managed to work it to his advantage. He hit his four doubles in Kansas City and his five hits against the Angels all with two strikes against him. “I hit better when I am behind on the count, after I have seen what the pitcher is throwing,” he explained. “I concentrate better.”

He was the complete package DH: able to hit for power to all fields, a tough out, and able to handle the pressure, even when he created extra amounts of it. Most importantly, those once wobbly knees had carried him to second for a team-high 21 doubles by mid-August. The fans at Fenway and those watching on televisions flickering throughout New England adored his swing, but they might have loved him best for his knees.

They’d seen how he had strained in his losing effort to beat out a ground ball in the opening series against the Yankees. They knew his history and his pain. So they appreciated his legging out the doubles—even when many of those would have been triples in years past—and they loved him best for the way he hustled out every ground ball, never letting the pain beat him. Gotta love the heart in that guy.

The Puerto Rican star was honored for his Hispanic heritage as part of “Latin American Day” at Fenway Park in July, along with eight other players from the Red Sox and Twins, before a game against Minnesota. Also in July, the Puerto Rican Businessmen’s Association of Hartford, Connecticut, selected Cepeda as the first recipient of its Roberto Clemente Award. Now that Clemente, beloved in his native Puerto Rico, was gone, Cepeda was the island’s reigning star. The Puerto Rican community of New York City honored “Baby Bull” before a Boston game at Yankee Stadium in September.

But it was in Boston where he became beloved not for his heritage but for his hitting. The city could be hard on its sports figures. The Boston public harbored a fifty-three-year-old resentment against Harry Frazee for selling Babe Ruth to the Yankees. They still begrudged Johnny Pesky for the hesitation on his relay throw in the seventh game of the 1946 series that allowed the Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter to score from first and rob them of victory. Hear the boos lobbed at Sparky Lyle when he took the mound for the hated Yankees. But Boston fans also loved a hero, and Cepeda was one for them.

When Cha Cha stepped out of the dugout to swing his bat in the on-deck circle, he looked to the stands. Fans shouted to him. He called back. Joking, bantering. It was a mutual love affair. He was playing out some of the happiest days of his career in Beantown.

The good vibes made him want to play more. He hoped his knees were strong enough to let him play the field again. He told reporters he dreamed “of returning to full-time duty at first base next season.” Despite his success in the DH role, he was still not content with the part-time work. The position still carried the stigma of the incomplete player, even for him.

Cepeda’s season made a strong case for the success of the DH experiment, which was intended to set off a chain reaction of increased offense, fan interest, attendance, and revenue. Results from around the league bore that out.

Designated hitters easily provided more offense than pitchers, whose natural strength was on the mound, not at the plate. Through the 1973 season, the twelve AL teams used 132 different players in the designated hitter role. Combined, they batted .257, nearly a 90-point improvement on the .169 combined average for pitchers and those who pinch hit for them the previous year. The designated hitters raised the AL’s overall batting average 20 points, from .239 in 1972 to .259 in 1973, which bested the NL’s overall average of .254 for the first time in ten years.

More hits meant more runs. In 1973 AL games, teams averaged 8.55 runs per game compared to 8.31 in the NL. American League teams averaged almost 25 percent more runs per game in ’73 than they had the previous season, 8.55 to 6.93.

Home runs in the AL were up to 1,552 from 1,484 in 1971, which makes for a better comparison because teams played fewer games in the strike-shortened ’72 season. Again, the designated hitters drove the pace with their power hitting. The designated hitters knocked in a run once every seven times at bat; pitchers had an RBI once every 20 times at bat the previous year. The designated hitters slugged 227 home runs, at a ratio of one every 33 at bats; pitchers homered 48 times, once every 217 at bats in 1972.

The experiment had improved offense, no question. Fans liked that. The Harris poll, taken during the season, showed 62 percent of respondents agreed with the statement: “By allowing a real batter to bat, instead of the pitcher, it means more runs and more action, and that’s good.” The Sporting News conducted its own poll around the All-Star break, figuring that its readers would provide a more knowledgeable view of baseball than the Harris poll’s sample of the general population. Fifty-two percent of The Sporting News’s readers polled favored the use of the DH, while 48 percent opposed it, not a large majority of support. Fans in American League cities, more likely to have seen the DH in action, did show stronger support for the new rule—57 percent for and 43 percent against—than in NL cities, where 52 percent opposed and 48 percent approved.

The key measure of the fans’ interest was revealed at the gate, where attendance showed a strong increase. Attendance at AL games reached an all-time high, with 13,443,016 clicks of the turnstile in 1973, a significant 1.6 million jump from 1971, the last full season. The National League still outdrew the junior circuit by more than 3 million with an attendance mark of 16,679,175, though that was down 645,682 from 1971. One possible explanation for the NL’s drop and the AL’s gain could be found in Chicago and New York, two cities that had teams in each league. The NL teams in Chicago and New York saw a 653,351 drop to the AL teams’ 673,873 gain from 1971 to 1973. The addition of the DH in the AL no doubt factored in the figures from those two cities, where both NL teams were involved in division races until the end of the season but neither AL team was.

Major league attendance overall set a record mark, topping 30 million for the first time. The AL accounted for most of the rise. That suggested that the DH experiment had helped fans get over the bitter feeling they had about baseball’s labor relations at the outset of the season. Nine teams playing better than .500 ball and two tight division races at the All-Star break also contributed to the AL’s increased attendance. The two five-team division races halfway through the season created “an unprecedented state which is having a beneficial effect on the gate.” The new ballpark in Kansas City alone nearly doubled the Royals’ attendance, up by 637,685 in 1973 from 707,656 in 1972. But the designated hitter was widely seen as the primary factor generating more interest and increased attendance throughout the league.

Fans also liked seeing their favorite stars play an extra season or more. The new DH rule extended not only Orlando Cepeda’s career, it added years to the careers of many players. The eight top designated hitters of the rule’s inaugural season—Cepeda, Tommy Davis (Orioles), Tony Oliva (Twins), Frank Robinson (Angels), Deron Johnson (A’s), Rico Carty (Rangers), Jim Ray Hart (Yankees), and Ollie Brown (Brewers)—were all aging players, many recovering from injuries, fit to bat but not to field, the early definition of the DH. All except Oliva had enjoyed success in the National League. Their reputations alone drew fans to see them in the AL, often for the first time. This had not been one of the stated objectives of the experiment, but it proved a popular side effect for the fans and lured them through the turnstiles.

Bowie Kuhn had said he would let the fans decide the fate of the DH experiment. By that, the commissioner meant if they responded by turning out in larger numbers, they would have their designated hitter. He wanted them to put their money where their opinion was, and they did. Each additional click of the turnstile deposited extra revenue in the owners’ pockets. What had started out as a three-year experiment had proven such a success that the owners voted after just one season to make the rule permanent.

A’s owner Charlie Finley’s lobbying for the new rule is widely credited for its eventual adoption. He found a measure of vindication in the decision. “At first, they thought I was nuts,” Finley said. “But after continuously harping, I finally woke them up.” Yet the AL owners’ vote remained far from the final word on the designated hitter.

The National League, content with its status quo, still wanted nothing to do with Finley’s permanent pinch hitter. Chub Feeney, NL president, said he had observed “no real interest” in the DH among NL owners. He credited the AL’s improved attendance to close division races, not the designated hitter. Opposition among NL owners to the designated hitter was so absolute that they rejected their AL counterparts’ request to use the DH in All-Star and World Series games played in AL parks.

Thirty-five years later, the leagues remain divided, the DH being the only rule on which they cannot agree. The rule also polarizes fans, managers, and players. “I screwed up the game of baseball,” Ron Blomberg said thirty years after he made history as the game’s first designated hitter. “Baseball needed a jolt of offense for attendance, so they decided on the DH. I never thought it would last this long.”

Some say Blomberg’s right—he screwed up the game. Others say he’s wrong. The argument usually pivots on the way the DH has—or hasn’t—diminished the game’s strategy. That was Feeney’s main objection in 1973. “I like the strategy and the fans do, too,” Feeney said. “And I think the DH rule takes some of that away. It deprives them of thinking along with the managers.” He still speaks for many fans, managers, and players today.

But not all. “Everyone in the world disagrees with me, including some managers, but I think managing in the American League is much more difficult for that very reason [having the designated hitter],” said Jim Leyland, who has won pennants as a manager in both leagues and skippered the Detroit Tigers in 2007. “In the National League, my situation is dictated for me. If I’m behind in the game, I’ve got to pinch hit. I’ve got to take my pitcher out. In the American League, you have to zero in. You have to know exactly when to take them out of there. In the National League, that’s done for you.”

The venerable Bill James backed him up. In The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, he demonstrated mathematically how the use of the DH actually increased the use of strategy.

Carl Yastrzemski and others had initially feared that the DH rule would endanger hitters by allowing pitchers to freely throw at their heads, unchecked by any fear of retribution. Minnesota Twins manager Frank Quilici believed the rule had the opposite effect, giving umpires the chance to better police the game and protect batters with warnings for suspected chin music. “The DH took away the fear of retribution by a pitcher who knowingly threw at a hitter and allowed the umpire to control the game instead of the unwritten rule in baseball that left it up to the players to decide when action should be taken,” Quilici said after he retired in 1975.

An economist and a mathematician from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, presented a paper at the Joint Mathematics Meeting in January 2004 that backed Yastrzemski’s claim. They called the DH a “moral hazard,” an economics term referring to “the idea that someone insured against risk is more likely to engage in risky behavior.” The pair, Charles Bradbury and Doug Drinen, figured pitchers who did not have to answer at the plate for their actions were more likely to throw at opposing batters. After a detailed analysis of eight MLB seasons, Bradbury and Drinen determined that the DH rule “increases the likelihood that any batter will be hit during a plate appearance between 11 and 17 percent.”

While batters worried about the moral hazard posed by the DH rule, fans continued to worry about the rule’s impact on the integrity of the game’s records, particularly among pitchers. They focused on Nolan Ryan.

The California Angels flamethrower finished the season with two no-hitters, though he nearly racked up four. In addition to the no-hit bid spoiled in the seventh by the Orioles’ Mark Belanger in his first start after Ryan no-hit the Tigers, Ryan had another no-hit game spoiled by the scorer, though no one realized the fact until it was too late to protest.

Against the Yankees on August 29, 1973, Ryan struck out ten, walked three, and retired the final fifteen batters in order. The only “hit” he allowed came in the first inning when Yankees catcher Thurman Munson hit a popup to shallow center. The Angels shortstop and second baseman gave chase. Both called for it. At the last instant, both backed off, and the ball dropped between them. The official scorer credited Munson with a hit, though if the play had occurred in the later innings of Ryan’s no-hit bid, the scorer would probably have given one of the infielders an error, following the traditional practice of requiring a clean hit to break up a no-hitter. That simple twist of timing kept Ryan from becoming the only pitcher in history to throw three no-hitters in a single season.

Ryan’s near-miss may have inspired heartbreak, but his pitching moment that provided the test case for the DH’s impact on pitching records occurred with Ryan’s final pitch of the 1973 season. On Thursday, September 27, he faced the Minnesota Twins first baseman Rich Reese in the top of the 11th inning. Ryan had already struck out 15 batters that day, tying Sandy Koufax’s single-season record of 382 strikeouts set in 1965. With a runner on second, two outs, and two strikes on Reese, Ryan threw an inside fastball by Reese for strike three and strikeout No. 383 on the season, a new record.

The Angels won the game in their half, giving Ryan his 21st win of the season against 16 losses for a team that was last in the American League in hitting, runs batted in, and home runs and that had lost more games than it won. The last-minute All-Star addition bested two more Koufax records that season. The Dodger great had struck out 10 or more batters 21 times in 1965; Ryan struck out 10 or more 23 times in ’73. Koufax set the modern record (since 1900) with 699 strikeouts in consecutive seasons; Ryan struck out 712 in 1972–1973.

Initially, it was thought that the new rule might reduce a pitcher’s numbers because the DH meant he faced tougher competition, a lineup of nine valid batters without the gimme out of the pitcher at the plate. By that measure, Ryan’s 383 strikeouts came against more difficult conditions than Koufax’s 382 in 1965, when he fanned the pitcher 53 times. Ryan had fanned pitchers 42 times in 1972, when he led the majors with 329 strikeouts, but struck out designated hitters only 30 times in 1973. The DH was a tougher out, but Ryan had still struck him out 30 times. In that regard, the DH rule had boosted the quality of the mark Ryan set.

The biggest boon to pitchers from the DH rule was that it allowed them to stay in games longer—instead of being lifted for a pinch hitter—and determine the outcome of the game. Ryan completed 26 of his 39 starts in 1973, throwing 326 innings, up from 20 complete games and 280 innings the previous year. Koufax pitched 27 complete games and 335.7 innings in 1965. Ryan’s strikeout record was deemed a legitimate besting of Koufax’s mark. “He [Ryan] might have struck out 400 [batters] if he was facing pitchers instead of designated hitters,” The Sporting News surmised. Ryan vindicated pitching records in the DH era.

By allowing a pitcher to stay in a game longer, the DH rule, originally intended to boost offense, had, ironically, produced a record number of 20-game winners (12) in the AL. In 1971, the last full season, 537 AL pitchers had completed their starts; in 1973, 614 did. “Beyond doubt, the DH enabled many a pitcher to remain on the job and win instead of bowing out for a pinch hitter,” The Sporting News observed in a year-end editorial. “That’s the only logical conclusion to be drawn from the AL’s twelve 20-game-victory hurlers, the highest total for one majors since the National produced 17 in 1889.”

Some pitchers remained adamant that the rule change favored the hitters, but there was no denying pitchers had also benefited from the change. The rule may have taken away an easy out and denied pitchers the chance to help their own cause at the plate, but it certainly allowed them to focus on their primary task, pitching, without having to worry about their turn at bat.

As the commissioner well knew, there was no pleasing all of the people, whether they were pitchers, managers, fans, or players. After only one season, the DH had become as certain in the American League as death and taxes in the United States.

The long season caught up with Cepeda in September, when he turned thirty-six. He pulled a muscle in his leg and had to sit out several games. He seemed to have lost his home-run strength, clouting only one tater all month. Prior to coming to Boston, he had stolen 141 bases, but he didn’t steal a single base all season. He also managed no triples. Certainly, in days of better knees, he would have stretched many of his 25 doubles into triples. With his current, worn-out knees, he ignominiously led the league in the number of double plays he grounded into, unable to beat relay throws to first. “If I could run, I’d be in the Kentucky Derby,” Cha Cha joked.

Still, worn-out knees and all, the Red Sox DH managed to finish the season with some impressive numbers. The man who had thought his career over the previous winter had batted 550 times in 142 games. His final home run, a three-run blast on September 26 that gave the Red Sox a 3–2 win over the Indians, was his 20th homer of the season and 378th of his career. His 15 game-winning hits led the Red Sox and tied him for fifth-most in the AL, seventh-best in majors. His 25 doubles had tied him with Yastrzemski for the team lead. Cepeda’s 15 game-winning hits were tops among designated hitters. His 20 homers and 86 RBIs were both second-best among designated hitters.

He scored 51 runs himself. Cepeda was named the Outstanding Designated Hitter of the year, the first recipient of the annual award established by the Manchester, New Hampshire, Union-Leader in cooperation with the American League. A seven-person committee of broadcasters, writers, and Hall of Famers selected Cepeda ahead of Tommy Davis and Tony Oliva. “Orlando Cepeda, whose career was revived by the American League’s designated hitter rule, has been named the outstanding practitioner of the substitute batting art in the 1973 season,” The Sporting News announced.

His numbers and the award seemed to confirm what The Sporting News had reported earlier about his successful debut as a designated hitter: “He will definitely fill the same role in 1974.” But it was not to be.

The Red Sox had finished second in the AL East division, a disappointing eight games behind the Baltimore Orioles, who had pulled away after the All-Star break. Boston fired manager Eddie Kasko on the last day of the season. His replacement, Darrell Johnson, was not a strong Cepeda supporter, the way Kasko had been. Johnson had come up the managerial ranks through the Red Sox minor league system. He had seen talent there that he wanted to bring to the big leagues. The thirty-six-year-old Cepeda, shortstop Luis Aparicio, a month shy of forty, and pitcher Bobby Bolin, thirty-five, stood in the way of Johnson’s youth movement. The new manager released the aging trio near the close of spring training the following season.

Cha Cha’s fans complained, but they could not win him back his DH spot. Neither his success nor his popular standing could guarantee Orlando Cepeda a job. His precarious position on the team mirrored that of the designated hitter’s place in the game. It was destined to delight some, to antagonize others, but never to rally united support.

About the author:

John Rosengren is an award-winning journalist and author. He has written five other books, including Blades of Glory: The True Story of a Young Team Bred to Win. His articles have appeared in more than one hundred publications, ranging from Sports Illustrated to Reader’s Digest. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research and the American Society of Journalists and Authors. A lifelong Twins fan, John lives in Minneapolis with his wife and their two children. Visit him at www.johnrosengren.net.

Fantastic stuff! Looking forward to this read.