Book Excerpt: The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness

Plus ICYMI, Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

You’ve read my rave reviews of the writing at the Athletic for some time, and today we celebrate one of the publication’s best wordsmiths. With number 27 in our book excerpt series, I am happy to recommend “The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness,” by Andy McCullough (Hachette Books, May 7, 2024, Hardcover $28.80, Kindle $17.99). While I admired McCullough’s work at the Los Angeles Times, and perhaps with the freedom to be more creative, I believe he’s taken it to a new level at the Athletic. And he is Syracuse grad, like my father, Mort.

“The Last of His Kind” is a lovely read. I’ve chosen a meaty section of a chapter called “The Shadow of Sanford” to excerpt here. It begins below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 9: The Shadow of Sanford.

The door swung open, and a silver-haired eminence entered the Dodger Stadium conference room. He wore a blue pullover, dark jeans, and black sneakers that emphasized comfort over couture. He looked eighty-seven going on sixty-five. His bearing was more genial than regal, despite his ability to cause a ruckus at a card show or a convention, despite the mob that would swallow him if he climbed a flight of stairs and walked the ballpark’s concourse.

Then Sandy Koufax extended his right hand. “Have you ever seen Sandy’s hands wrapped around a baseball?” Clayton Kershaw once asked. The legend of Koufax bloomed for many reasons—spiritual, technical, philosophical. Some of it was just genetics. “He doesn’t have hands,” a teammate replied. “He has paws.”

Koufax pulled up a chair. To his right, a framed illustration hung along the wall. In the painting, Jackie Robinson, clad in a white shirt and blue tie, smiled beside a southpaw from Brooklyn, the man with The Left Arm of God, grinning in his crisp, No. 32 uniform.

Every pitcher at Dodger Stadium lives in the shadow of Sandy Koufax. Even, at times, the man himself.

The comparisons started at the beginning. Sometimes Dodgers people blamed the press. When the Dodgers selected Kershaw, a left-hander with a hellacious overhand curveball, the writers likened him to the franchise’s most famous left-hander with a hellacious overhand curve ball. But Dodgers officials indulged the temptation. “I’m the one who opened my mouth and said he reminded me of Koufax,” Joe Torre recalled. He wasn’t the only one. Marty Reed, the minor-league pitching coordinator, sat in a meeting at the end of 2007 with the brass. “I don’t know if I should say this,” he told the group. “But he might be the closest thing to Sandy Koufax.” By the spring of 2008, the sentiment was not limited to private discussion. “You’re praying he’s Koufax,” Logan White told the Press-Enterprise of Riverside, California.

In those years, Koufax still roamed Dodgertown each spring. Rick Honeycutt, who had become a Koufax disciple while pitching for the Dodgers in the 1980s, encouraged his friend to check out the team’s top prospect. “Wait ’til you see this kid,” Honeycutt said. Koufax kept his interaction with Kershaw brief. “Good luck,” Koufax told him.

This was the land of hopes and prayers that Kershaw inhabited that spring, after he humbled Sean Casey, after Vin Scully compared his curveball to John Dillinger’s tommy gun, after he crossed the bridge to big-league camp. He was still a teenager. He could only throw two pitches. He had pitched in four games above class-A baseball. And yet the team openly wondered if he could grace the celestial plane established by Koufax, the organization’s patron saint of pitching, the three-time Cy Young Award winner who walked away from the game at thirty, the living deity still worshipped from coast to coast.

All that stood between Kershaw and the chance to emulate Koufax was the Dodgers front office. Ned Colletti had authorized Kershaw’s rapid ascension through the minors the previous year. But he held the line when Joe Torre’s staff clamored for Kershaw to break camp with the big-league club. “I remember Larry Bowa going, ‘How about the Kershaw kid? Why don’t we just take him?’” recalled catching coach Mike Borzello. “And Ned’s like, ‘No, no, no. He’s not ready yet.’”

The Dodgers sent Kershaw back to Jacksonville. To ease his passage out of the minors, the team promoted Glenn Dishman, his pitching coach in Midland. The organization intended to challenge Kershaw while treating him with care. It was a delicate dance. Dishman maintained steady dialogue with Colletti and Reed. There were the usual changeup quotas. Dishman monitored Kershaw’s pitch count closely. The Dodgers did not want Kershaw to expend too many bullets against the Tennessee Smokies or the Montgomery Biscuits.

Kershaw chafed at mandates. On the endless bus rides, he would tell fellow pitching prospect James McDonald he was sick of changeups. He toiled with the pitch, often against his will, to satisfy superiors who he believed did not understand his body as well as he did. “He would get frustrated with it, when they were trying to force him to do things,” McDonald recalled. “He was just like, ‘I’m not throwing it. I’m done doing that. I’m going to be Kershaw. I’m not trying to be who they want me to be.’” He disliked being told what to throw before the game, rather than choosing during the heat of competition. “If I had his fastball, why wouldn’t I want to throw it by people?” Dishman recalled. The pitch counts were tougher to argue against. The Dodgers were training Kershaw to be able to throw a hundred pitches or more in a game in the majors. But the club did not want to overexpose him in less consequential settings. All teams faced this conundrum when develop ing pitchers: how do you build stamina without risking injury? Kershaw believed the only way out was through. “You know I can go further than that,” he would say after being informed he could only throw five innings or seventy-five pitches in a given outing. Dishman counseled Kershaw about the big picture. The message did not always land. “It was always a tough day when you knew Clayton was only going to have a certain amount of pitches,” Jacksonville manager John Shoemaker recalled.

Kershaw grumbled while abiding by the restrictions. He had thrown 122 innings in 2007; the Dodgers did not want him to exceed 170 in 2008. In his first month in Jacksonville, he pitched into the seventh just once. The Dodgers responded by skipping his turn in the rotation and giving him ten days off. The handcuffs did not hamper his results. He was striking out about a batter per inning. His command improved. He discovered that he did not need to chase strikeouts. If he threw his fast ball or his curveball in the zone, Cody White recalled, “People just couldn’t hit it.” To Shoemaker, Kershaw personified what Tommy Lasorda, the organization’s cartoonish sage, used to tell prospects: “Walk out onto the field and act like you’re the best ballplayer on the field—but just don’t tell anybody about it.”

Kershaw’s presence brought heightened attention to the club. “It wasn’t just the Jacksonville Suns,” recalled outfielder Adam Godwin. “It was the Jacksonville Suns and Clayton Kershaw Show.” Kids at the Baseball Grounds of Jacksonville hounded him for autographs. So did the ladies; teammates occasionally teased Kershaw for refusing to chat up women who sought his acquaintance. When the Suns auctioned the players’ pink jerseys for breast cancer awareness, Kershaw’s led the bidding at $800. He stayed humble, several remembered. He drove a Chevy Tahoe purchased with insurance money he recouped after flip ping his dream car. One afternoon, a few players ventured to the outlet malls. Kershaw found a pair of Under Armour sneakers he liked on sale for $49.99. “I like these,” Kershaw told Godwin. “I’m not going to get them, though. They’re too expensive.” Godwin thought Kershaw was kidding. Then he watched him leave the store. A similar scene had unfolded at a Sunglass Hut in Florida in 2006. “There was a pair of Oakley sunglasses for $100,” Dave Preziosi recalled. “And he just couldn’t justify paying that money.”

Teammates needled Kershaw for his refusal to part with a buck. In Midland, he slept on Walmart air mattresses until they collapsed under his weight. He exchanged the busted mattresses for new ones. “It was very unethical,” Kershaw recalled. “But I did it. I tried to live as cheap as possible.” He heard cracks about his disdain for pants, his limited rotation of free Under Armour polo shirts. “He doesn’t dress overly loud like, ‘Look at me, look at me,’” Trayvon Robinson recalled. “I don’t think he owns a chain, to be honest. His personality doesn’t spark like, ‘Okay, I’m going to get a two-hundred-thousand-dollar car.’” (Kershaw did wear a diamond-encrusted cross in the majors. “I’m not cheap anymore, I don’t think,” he said. “But I definitely have no interest in buying, like, the finer things.”)

Kershaw rented a condo near the ballpark with McDonald and pitcher Brent Leach. “We always joked with Clayton that he was the cheapest guy,” McDonald recalled. “Like he didn’t want to spend noth ing. ‘This TV is going to be a small TV.’ ‘We don’t need cable.’ He was always smart, realistically, about spending.” McDonald wondered why Kershaw didn’t splash his bonus money around. In time, Kershaw told his roommate about his childhood.

“When he was growing up, he didn’t have his father in his life like that,” McDonald recalled. “It was his mom. So he did whatever he could to help her, and make sure she was going to be all right.”

In late May, the Suns took a seven-hour bus ride from Jacksonville to Zebulon, North Carolina. Kershaw was slated to make his tenth appearance of the season. He had struck out forty-five batters in 42.1 innings, with a 2.34 ERA, but innings restrictions had prevented him from recording an actual victory. After Kershaw retired the side in the first inning on May 22, Shoemaker sidled up to him.

“You’re done,” Shoemaker said.

Kershaw protested. Shoemaker did not budge. Dishman offered no explanation. Kershaw retreated to the clubhouse and iced his arm. He had eight innings to stew. He racked his brain. What could this possibly be about? The answer should have been obvious. A couple of weeks earlier, the Suns reorganized their rotation so Kershaw would make his big-league debut on May 17. Then Kershaw surrendered five runs and couldn’t finish the fourth inning against the Mobile BayBears. The Dodgers delayed his promotion. Kershaw wondered if he had botched another opportunity.

After the game, Shoemaker called Kershaw into his office and handed him a phone. On the line was Colletti: the Dodgers needed Kershaw to start in three days. Colletti asked Kershaw to keep the news quiet. Kershaw wanted to play it cool, but his head was swimming. Once he stepped outside the clubhouse, he opened his phone.

“Ellen, don’t tell anybody,” he said. “But I got called up.”

Then he told her to tell everybody. His mom. Her parents. His friends. He asked her to search his closet for his suit; he only had shorts and T-shirts with him, and he didn’t want to look ratty when he reached the majors.

By the next day, the other Suns had figured out what was going on. He stood apart from the group, even if they considered him part of it. “It’s like, ‘Hey, they’re going to call Kershaw up, and I’m going with him!’” Godwin recalled. “We all had dreams and goals and missions.” Kershaw was much closer to fulfilling his ambitions than the others. As he headed to the airport, he started thinking about his first opponent, the St. Louis Cardinals. His excitement gave way, ever so slightly, to fear.

A car picked Kershaw up at Los Angeles International Airport and hustled him to Dodger Stadium. Inside the clubhouse, the inner sanctum of the best of the best, he dropped his duffel bag and gawked at the cleanliness, the orderliness, the stars gathered around him. The team gave him a locker next to veteran pitcher Jason Schmidt, a three-time All-Star with the San Francisco Giants who was midway through a disastrous Dodgers tenure. The club had signed Schmidt for $47 mil lion, only for Schmidt to show up with an injured shoulder. When Kershaw debuted, Schmidt couldn’t really throw. But he could still pull a prank.

Jazzed about his opportunity, unsure of his surroundings, Kershaw reached into a locker and grabbed a jersey. It was not his. Schmidt saw the rookie sporting a No. 29 with SCHMIDT on the back and told his teammates to dummy up. Schmidt put on Kershaw’s No. 54. When the players lined up for the national anthem, Schmidt instructed Kershaw to stand beside him. The big screen at Dodger Stadium showed Kershaw’s face. And then it cut to the back of his jersey, where another man’s name was spread across his shoulders. The crowd and the rest of the players cracked up. Kershaw thought the song would never end.

After the game, he met his friends at his hotel. Ellen had come through. A twenty-three-person fleet had made the trip from Texas. Marianne Kershaw and Leslie Melson were there. Kershaw gabbed with his crew before heading to bed. Alone in his room, he thrashed around, staring at the tableside clock. After a while, he called Ellen, who was staying in a separate room at the hotel. She calmed him with their shared belief that God controlled his fate the next day. Kershaw felt his heart rate slow. After they said goodnight, he managed to get a few hours of rest.

In the morning, he sat alone in the Dodgers clubhouse, overwhelmed with the swirl of emotions. In the years to come, he leaned into the comfort of his routine to ease his mind. But on his first day, he rode the waves. He was too amped to notice the hoopla, his starring role in this seismic event in franchise history. Koufax offered encouragement before he took the mound. In the dugout, Kershaw felt his heart hammering in his chest. He remembered what Ellen had told him. He said a few words, which he would repeat before every subsequent start: “Lord, whatever happens, be with me. Be my strength.”

Across the field, the St. Louis hitters were unsure what to expect. The scouting report on Kershaw was brief. A few players studied video clips. Cardinals outfielder Rick Ankiel approached his agent, Scott Boras, who frequented games at Dodger Stadium. Seven years earlier, Ankiel had been a phenom, a pitcher whose left arm supplied lightning. A mysterious inability to throw strikes nearly ended his career before he reinvented himself as a hitter. He knew Boras, who had been unable to convince Kershaw to attend college, kept tabs on all the top prospects. “He’s the next Rick Ankiel,” Boras said. Ankiel and his teammates scoffed. “We’re like, ‘He ain’t no Rick Ankiel,’” infielder Skip Schumaker recalled. Under future Hall of Fame manager Tony La Russa, the Cardinals possessed a pride that bordered on haughtiness. “Our whole thing was ‘We’re not going to get beat by a twenty year-old. We’re the Cardinals,’” recalled infielder Aaron Miles.

Schumaker, the St. Louis leadoff hitter, had spent his entire career as a Cardinal, a modestly talented ballplayer who maximized his talents, molded by a player-development system designed for La Russa. Schumaker figured Kershaw would be too nervous to throw anything but fastballs. At 1:10 p.m., Kershaw wound up to pitch in the majors for the first time. His legs and hands rose in concert. Up. Down. Break. One. Two. Three. The fastball disarmed Schumaker. “It came from a spot where I just could not see it,” Schumaker recalled. The video had not prepared him for this. He hung around for seven pitches, fouling off four, before Kershaw pumped a 95-mph fastball past him.

Inside the dugout, Schumaker spotted Ankiel. “Ricky,” he said, “he’s better than you.”

Kershaw permitted himself a smile. His first big-league strikeout resided in the record books. He extended his glove to catcher Russell Martin. Martin tossed the ball toward the dugout, where it could be commemorated.

“Can I have the ball back?” Kershaw said. “Relax,” Martin said. “Here’s a new one.”

The rest of the inning demonstrated the challenge ahead. Unable to locate his fastball, Kershaw walked outfielder Brian Barton. Up next was Albert Pujols, an imperious slugger who had already won one National League MVP award and would win two more. He excelled by combining patience with power. He waited for mistakes and then punished them. With a full count, Kershaw thought he might surprise Pujols with a curveball. Pujols smashed it for a run-scoring double. Kershaw chuckled to himself. This, he realized, would not be easy.

His first inning lasted thirty-two pitches. St. Louis ground pitchers to dust through tenacity. The Cardinals could not crush his fastball. But they could nick it, redirect it, do anything to keep Kershaw working. He responded by challenging them in the zone. “Every once in a while you face a kid making his debut and you just instantly know that it’s not normal,” reserve infielder Adam Kennedy recalled. In the sixth, Kershaw gave up another run, but he finished the inning with the game tied and a pitching line worth savoring: six innings, five hits, two runs, one walk, and seven strikeouts. He did not collect a win, but the team did. Kershaw cheered from the dugout as outfielder Andre Ethier delivered a walk-off hit in the tenth inning.

After the game, Kershaw met Ellen, Marianne, Leslie, and the rest of the Highland Park contingent. He had changed into an orange T-shirt and the navy suit Ellen brought. The gang posed for pictures with all their friends, the happy couple in the center of an Aéropostale ad. When Leslie returned home, she told her husband she sensed things between Ellen and Clayton were getting serious.

Kershaw bid the group farewell and boarded a bus to the airport. His friends were going home. He was headed to Chicago and New York. Most of his buddies had just finished sophomore year in college. He was the youngest pitcher to debut in the majors that season. He was the first member of Team USA to do so. Tyson Ross was a junior at Berkeley. Shawn Tolleson was just getting back on the mound at Bay lor. The Diamondbacks had traded Brett Anderson that winter; he was pitching for one of Oakland’s class-A teams.

Kershaw had beaten his goal, to reach the majors by his twenty-first birthday, by 298 days.

“This is a dream come true,” he said after the game. He had made it.

About the author (via the Athletic):

Andy McCullough is a senior writer for The Athletic covering MLB. He previously covered baseball at the Los Angeles Times, the Kansas City Star and The Star-Ledger. A graduate of Syracuse University, he grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia.

ICYMI:

Last week I noted what I hoped might be the final news items relating to the Dodgers’ disgraced translator, Ippei Mizihuara, for a while. But alas. Now former Angels infielder David Fletcher is under Major League Baseball investigation for placing illegal sports bets with the very same bookmaker, a crook by the name of Mathew Bowyer. And the beat goes on.

On a more pleasant note, the jersey worn by Babe Ruth, when he purportedly called his home run shot in the 1932 World Series, will be auctioned by Heritage Auctions in August.

MLB.com’s early-MVP poll is out, with Juan Soto leading the way in the American League and Mookie Betts in the National League.

Regular readers of this column know of my fondness for Zack Greinke. I just love everything about the guy. In no particular order, I love his Hall-of-Fame worthy pitching, his hitting, the pinch hitting in the World Series, Gold Glove fielding, running (nine steals in nine career attempts before finally being caught in 2019 at the age of 35) and his personality. I love the fact that he is the Dodgers franchise leader (that’s Brooklyn and Los Angeles) in two important categories — earned run average (2.30) and winning percentage (.773). I miss watching him play and hope to again someday. Which might happen. He’s working out at Diamondbacks’ facilities trying to determine if a comeback is in order. I certainly hope so. And if anyone has any leads, I would love to buy an autographed bat — Los Angeles or Kansas City only, please — or trade him for one. I have a unique item I believe Greinke would like. It’s something that no one else has.

I’ve thought of Blake Lively every time I’ve seen “B. Lively” in a box score for two years running. Because I’m a dude. And now it’s a thing:

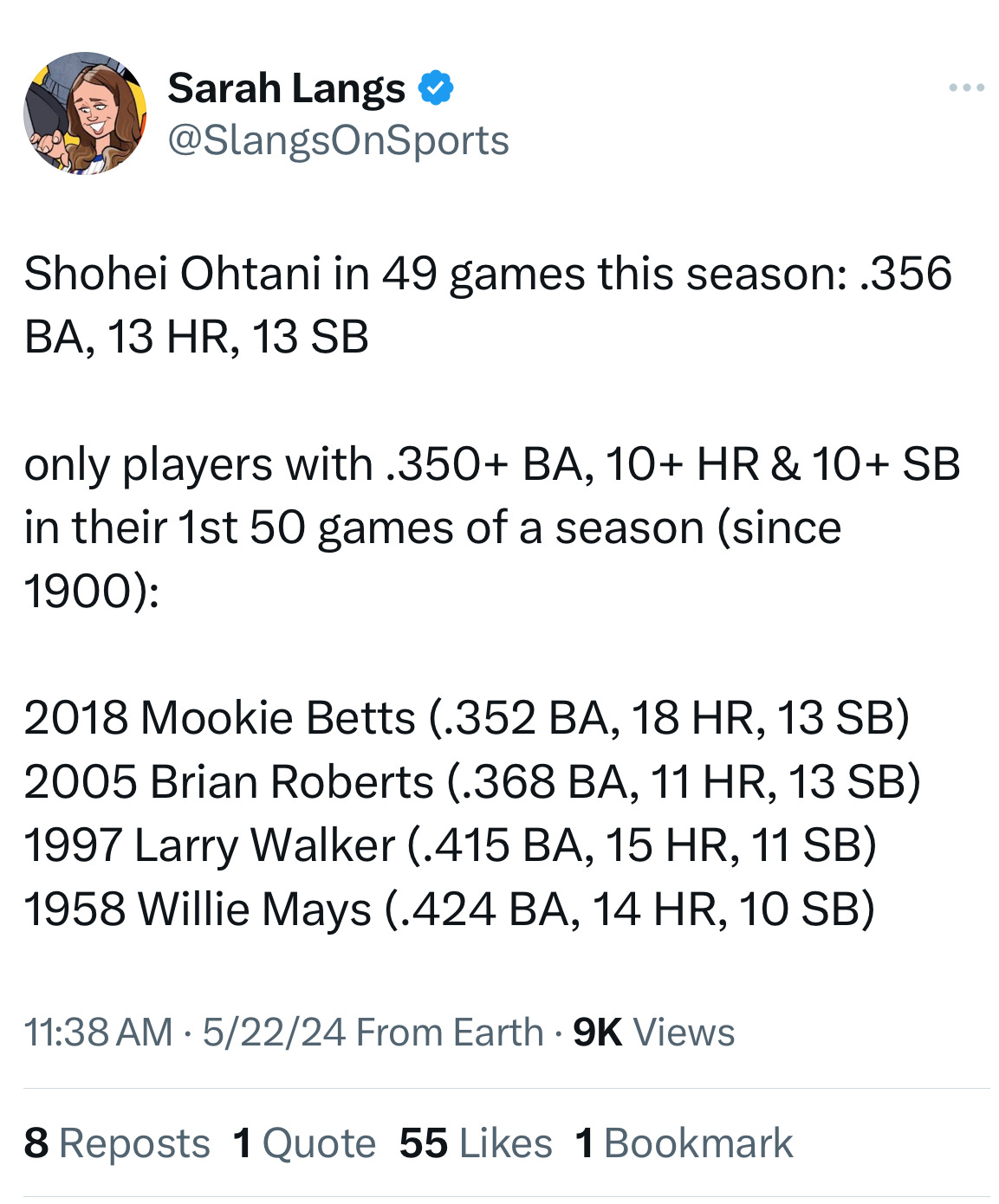

Stat of the Week:

Media Savvy:

Looking for more great writing recommendations from the Athletic? I’m your man.

Here is “Transition of Dodgers’ Walker Buehler hits its next stage with long-awaited win,” by Fabian Ardaya. Also by Ardaya is “Three Dodgers takeaways: Mookie Betts’ glove, James Paxton’s cutter and pitching depth.” And “Yoshinobu Yamamoto keeps rolling and adapting for Dodgers: ‘It’s special’” also by Ardaya.

Since all conversation about the Dodgers and pitching is relevant, and has been since the club moved from New York to Los Angeles following the 1957 season, here is one more: “‘He’s turned into a weapon.’ How Michael Grove became a high-leverage Dodgers reliever,” by Mike DiGiovanna at the Los Angeles Times. (Please note that I chose this story prior to Grove’s Tuesday meltdown and didn’t feel like cutting it afterwards.)

Finally, three from baseball historian Bill Arnold:

1. The A's became the sixth team since they moved to Oakland in 1968 to score 40,000 runs when Max Schuemann crossed home plate after belting one over the fence in the fifth inning against the Mariners in Seattle on May 12. Other teams to plate 40,000 or more runs since 1968 are the Red Sox (43,616 runs), the Yankees (42,720), the Rangers (41,069), the Guardians (40,340), and the Twins (40,257). Through Thursday, the A's had pushed across 40,007 runs. Two teams are on the cusp of joining the 40K club this season: the Orioles, 11 runs shy, and the Tigers, who'll need 47.

2. When outfielder Jacob Hurtubise debuted as a pinch-runner after being called up by the Reds last week, he became just the second West Point, N.Y., U.S. Military Academy graduate to play in the majors, joining Oriole RHP Chris Rowley (2017-18). Only three other military academy grads have reached the bigs: pitchers Willard "Nemo" Gaines (1921, Senators), Mitch Harris (2015, Cardinals), and Oliver Drake (Orioles, Brewers, Guardians, Blue Jays, and Rays, 2015–20), all alumni of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. The Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Co., has yet to produce a major-league player.

3. According to Mike Hughes of the Elias Sports Bureau, when Oriole catcher Adley Rutschman hit his walk-off home run against the Jays [last] Wednesday, he saved the Os' ongoing streak of 105 consecutive regular-season series played without once being swept. Only three other teams have managed the feat: the 1942-44 Cardinals (124 consecutive series), the 1906-09 Cubs (115), and the 1903-05 Giants (105). The Birds' binge began somewhat ingloriously in May of 2022 when they scrounged the final game of a series against the Yankees, denying the Bombers a four-game sweep.

Baseball Photos of the Week:

Lucille Ball and Julie Andrews.

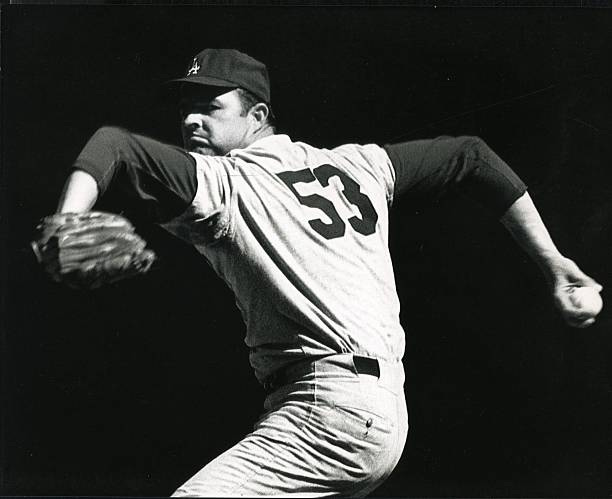

Don Drysdale.

Ray Oyler, Seattle Pilots, 1969.

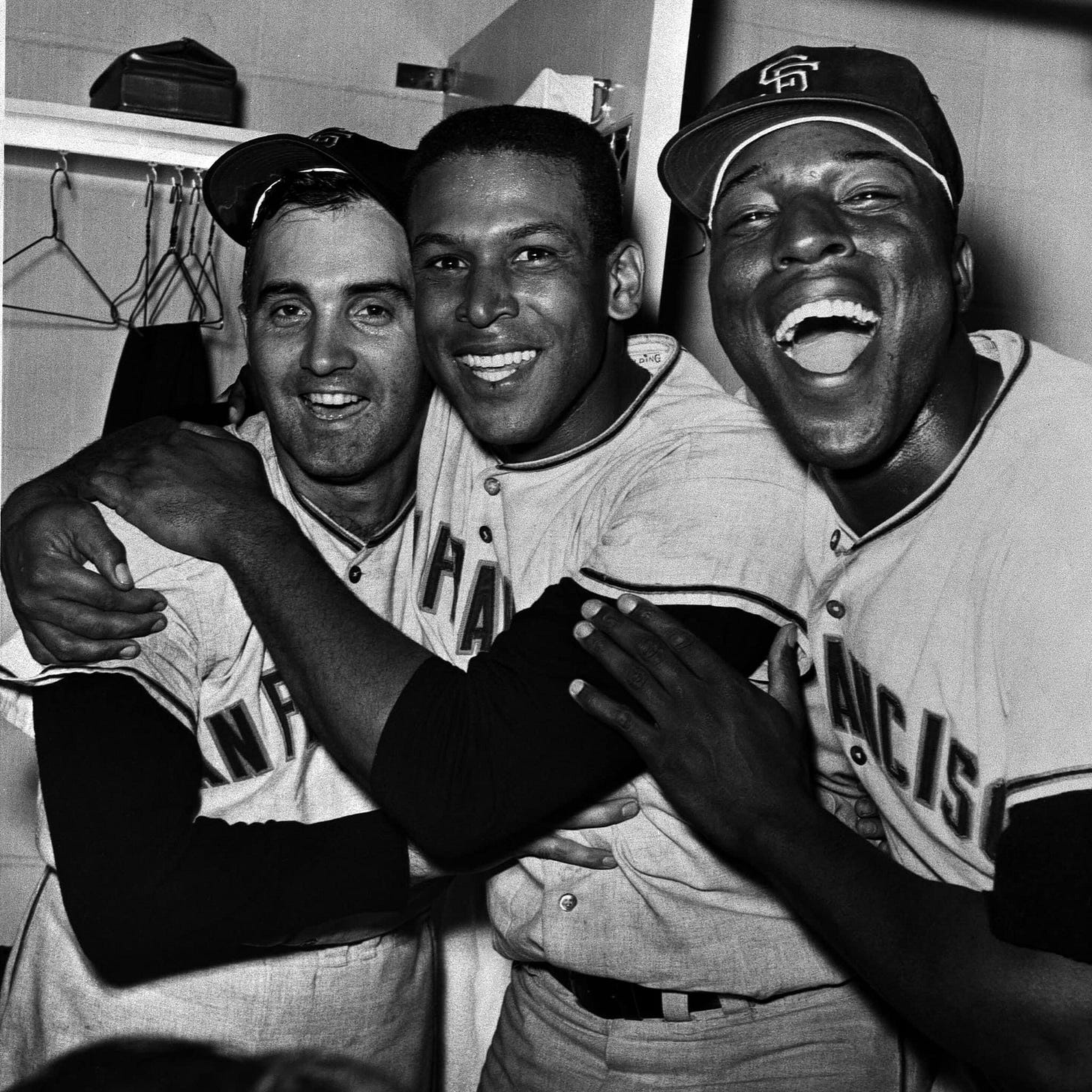

Billy Pierce, Orlando Cepeda and Willie McCovey. I suppose this picture was taken in the bowels of Dodger Stadium after the tragedy that was the 1962 three-game playoff. And you know what I say to that, don’t you? “Too soon!!”

Roger Maris.

Same photo, 1958 Topps Maris card.

Clayton Kershaw in the bullpen at Chavez Ravine, May 18. Photo by loyal Dodger fan and Twitter personality, Adrienne.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.

I’ve been saving this to savor it.

Yes, too soon, and the worst thing Uncle Walt ever did.