Book Excerpt: The Saga of Sudden Sam: The Rise, Fall and Redemption of Sam McDowell

Chapter 13: Gateway to Sobriety

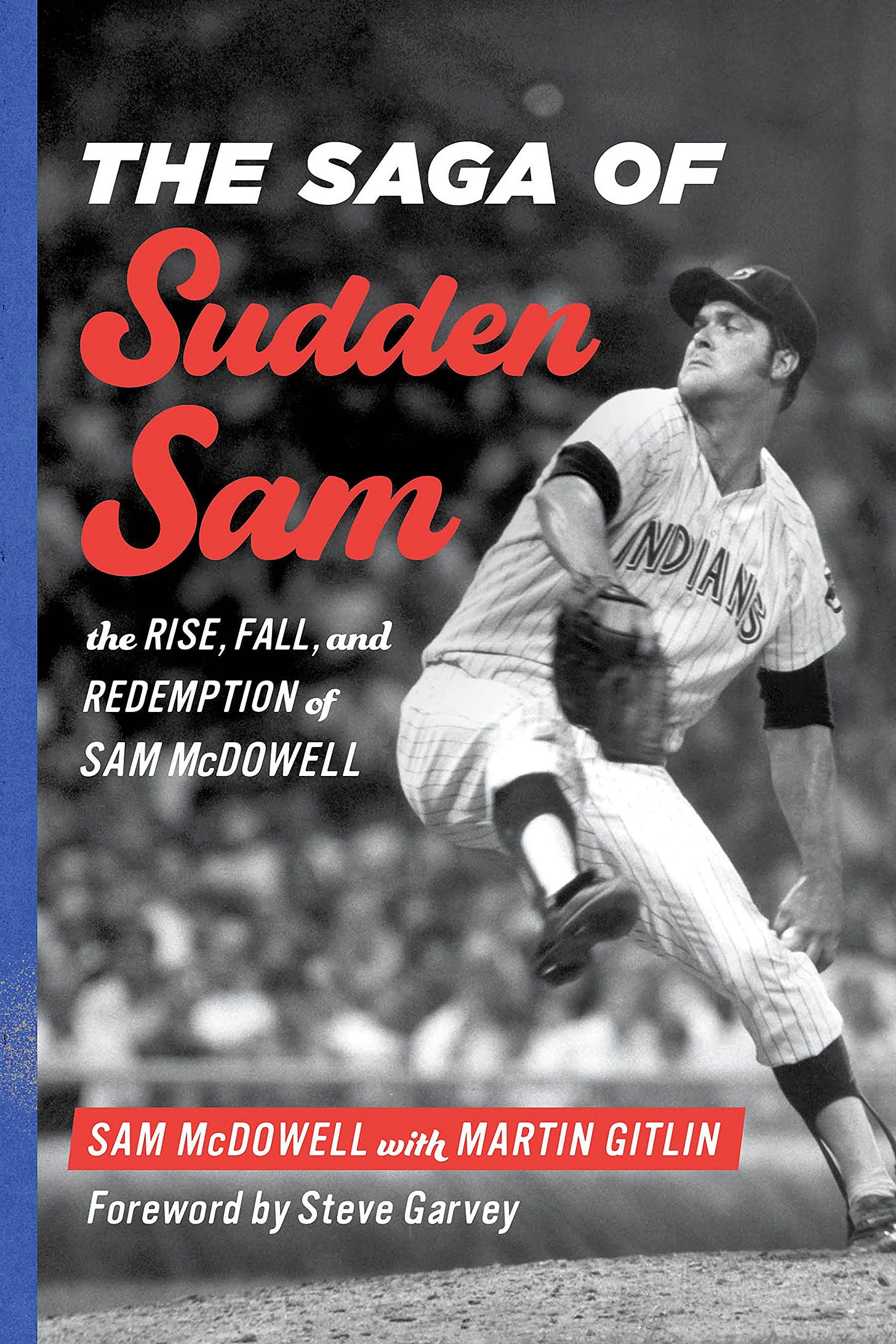

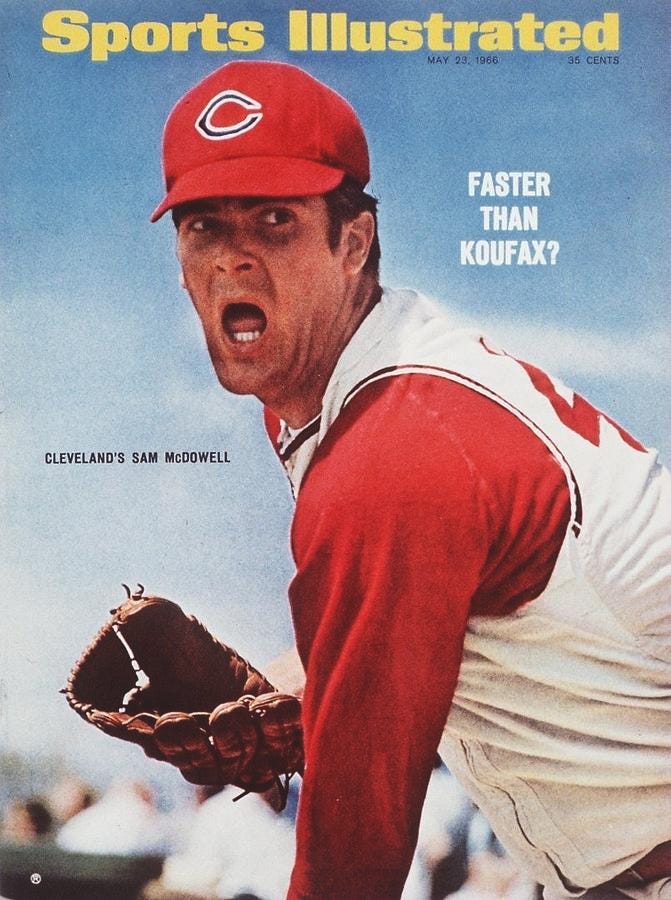

As a child of the 1960s and a baseball fan from the crib, I knew about and admired Sam McDowell. What I didn’t know until recently was that he drank himself out of the game. Since I had drunk myself out of whatever life I had in the 1990s and then gotten sober, I was intrigued by the left-hander’s story, and eager to read his new autobiography “The Saga of Sudden Sam: The Rise, Fall and Redemption of Sam McDowell,” by Martin Gitlin (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2022, Kindle $19.49, Hardcover, $22.91, autographed and personalized hardcover, $48.00, here).

The first 11 chapters amount to the rise and fall part. It reads like a drunk-a-log, which one might hear in a 12-step meeting, and it isn’t pretty. Compelling, yes, but what interests me most is McDowell’s inspiring story of recovery — how he got sober in 1980 and has trudged the road of happy destiny since — which begins with “Chapter 12: The Lost Years” and continues with “Chapter 13: Gateway to Sobriety,” which is the chapter I have chosen to excerpt, below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Excerpt: Chapter 13: Gateway to Sobriety:

Those who do not understand the alcoholic personality might be flabbergasted to learn that I remained unaware of my addiction as I arrived at the Gateway Rehabilitation Center in 1980. After all, how could anyone who embarked on a 10-day drinking binge, passed out in his car overnight in freezing temperatures, and lost his wife and kids not know he was an alcoholic?

But it was true. I knew something was seriously wrong with me, which is why I checked into the facility. My assumption, however, was that I was insane. Addiction is never obvious to the addicted. That is why it is known in the field of medicine as the most treacherous of all diseases as the body and mind demand the chemical, supplant all of our normal survival characteristics such as love, shelter, food, sex and warmth. There was a chemical imbalance within me from birth that automatically altered the frontal lobe, thereby numbing or desensitizing the area of the brain affecting such thought processes and emotions as critical thinking, fear, logic, and judgment. And because of all the chemical changes and differences in an addicted person, once he or she partakes in a mind-altering substance such as alcohol or a drug, the chemical becomes paramount in that person’s hierarchy of the above survival instincts.

I indeed believed I was insane. I wrongly assumed that if I were an alcoholic, I would be capable of controlling my intake. I felt that I had proven my exceptional will power throughout my amateur and professional baseball career and that I could win any battle with determination alone. I had also extensively studied basic and abnormal psychology through books and tapes during my playing days. I ignorantly related what I was experiencing to many of the disorders I learned about. Therefore, I must be crazy. And I embraced that belief with deadly seriousness.

The first week of my 30-day in-patient stay proved uneventful and unexciting. It was designed to ensure that I was stable physically and mentally and that detoxification was not necessary. Cutting off alcohol can prove dangerous and life threatening to an alcoholic. It can result in shock or even death. I soon underwent a complete psycho-social interview to provide the Gateway therapists with a synopsis of my emotional and psychological health. The initial concerns are depression and the possibility of suicide. I was interviewed during a counseling session to determine if other problems existed within me, such as mental illness or other disorders. Addiction is a primary disease, which means no matter what other issues were present, including mental illness, the alcoholism required the initial focus and treatment. If the addiction is not addressed first there could be no help, cure, and resolution.

Since I was deemed stable the therapy and educational aspects of my treatment could begin during my second week at Gateway. I underwent one-on-one counseling with a licensed therapist three days a week. That transformed my addictogenic personality and mindset to a normal, healthy one that would lead me to exhibiting more appropriate behavior. During that same period in rehab, we attended seminars that educated patients like me all about addiction, including how we contracted it. The sessions taught us that the disease is genetic. It showed us the chemical changes in the brain and its resulting abnormal workings of the pain and pleasure centers, as well as the altered state of the decision-making part of the mind, which is in the frontal lobe.

What an incredible learning experience! The relevance to every patient as we sat in the same room felt palpable. Those that took the sessions seriously (some who had been legally forced to attend and apparently had no intention of changing did not) understood what was being explained to them. I could see it in their body movements, their simple head shakes. I strongly sensed that going to Gateway had been mandatory for those who had not physically reacted. They had sadly allowed the teachings stream into one ear and out the other. But most of the patients soaked it in and took it sincerely. After the talks, when we were all alone, we discussed what we had just heard.

Soon came the greatest epiphany of my life. I had assumed upon my arrival at Gateway that I suffered from a mental illness because I had tried everything to stop drinking and failed, though such a claim could certainly be refuted. After two weeks of rehab, I realized I had a bonafide disease. That mistaken identity had been greatly a product of the times. Addiction for decades well into the 1970s had been considered a character flaw, mental illness, a psychological defect. The physical research data proving otherwise was uncovered late that decade by a researcher who studied cancer tumors and found tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) in the brains of alcoholics, but not normal people.

Since her discovery new research has confirmed that addiction is a disease. One finding at the Carnegie Mellon Research Center in 2005 showed in alcoholics and other drug addicts that their frontal lobe, which controls our fear, logic, and sense of reality and decision making, is anesthetized. It also demonstrated that the frontal lobe regenerates after 16 to 18 weeks of proper recovery from addiction. Doctors have marveled in recent years about what they see in their patients after that length of recovery. It is no longer a theory. It is a proven fact based on nearly a half-century of research to which I can certainly attest.

I was truthful about my thoughts, feelings, and life story from the start at Gateway. But I was quiet and noncommittal. I felt skeptical about how the struggles and commitments that laid in front of me could solve my problems. The ignorance of my belief system had been so cemented over the years that I could not see any light at the end of the tunnel. But I opened up quickly. I could see that all the addiction patients were in the same boat. We were all drunks or drug addicts with similar behavioral issues.

Twerski came to the rescue willingly and passionately. My amazement at his story and admiration for his work continued to grow with time and exposure. He was an orthodox Jewish rabbi who died at age 90 in 2021. He graduated from the Marquette University medical school in 1960, trained in psychiatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and later headed the department of psychiatry specializing in alcoholism and addiction at St. Francis Hospital. He combined his Rabbinical teachings about morality and ethics with his education in psychiatry before opening Gateway, which has helped thousands of people gain new leases on life. Twerski was a strong believer in the twelve-step recovery program embraced by Alcoholics Anonymous. I embarked on it after my stay at Gateway. It allowed me to remain on the path to mental, emotional, and physical health.

Other therapists worked the day-to-day therapy and counseling during my time at Gateway while Twerski served as the medical director who provided physical examinations and ran most of the educational seminars. We watched films about addiction and received a tremendous amount of educational material, including one book simply titled “The Big Book,” which is the bible of Alcoholics Anonymous, a pathway to success for those in recovery.

Carol and the kids were invited into the facility to confront me with their thoughts and feelings. That was quite an eye-opener. It proved very emotional for me because I had been so wrapped up in my own life that I had been deaf and blind about how my addiction was affecting them, as well as my parents. My mother called my therapist unbeknownst to me and asked for advice regarding my return. Should we hide the booze in our house? The answer was no. Should we talk avoid talking about our son’s alcoholism? No, talk about it often. Should we make sure he attends his Alcoholics Anonymous meetings? No. If he goes, he goes. But show faith in your son.

Toward the end of my time at Gateway all the misconceptions I had about my drinking problem had been educated out of my mind. But the recovery had barely begun. The potential of falling back into bad habits were frighteningly real to all who left the premises. The seminars in our final days at the Center focused on our new, sensitive, realistic, healthy psyche and how to maintain it. It was all new to us recovering addicts. We were told never to get too hungry or lonely or tired or angry. Those were cues that could launch a relapse process. They might start a chain reaction that trigger a setback into old and dangerous behavior. We were warned that the old addictogenic thinking within our subconscious would remain for quite some time. It would yearn for that old feeling that would give me an excuse to start drinking again.

I had to be aware of my thirty years of thinking a certain way. Now all of that had changed. We had been therapeutically taught a new way of reasoning and acting. The goal was to continue that path so I could ultimately change into a realistic, honest, logical, decent human being.

Gateway was a test. But it was not the ultimate test. It was a controlled environment. My honesty with Twerski and the therapists, willingness to soak in all I learned, and desire to rid myself of a debilitating disease were positive steps. Yet they would mean nothing if I could not apply my new knowledge practically. My understanding that alcoholism is a treatable disease rather than a reflection of my weaknesses gave me hope and strength. Now I needed to continue the path to sobriety and wellness.

Mission accomplished. Though it takes up to four months for recovering to recognize a magnificent change in oneself that can be perceived as a miracle, my loved ones noticed a nearly immediate difference. Before leaving Gateway on May 1, I was taught what to expect internally after six weeks and beyond if we embraced the special twelve-step program.

Among those who required far less time to recognize a positive trend was Tim. I have spoken often with him about his observations at the time. He detected that I began living my life so differently that he felt in his heart that I was destined for a permanent and wonderful change. He observed my mindfulness about everything I did, particularly my strict adherence to attending AA meetings as if my life depended on it, which I believed it did. Tim told me that he was unaware that I felt my very existence hinged on strict adherence.

He also remarked that he began to see me as the humblest human being he had ever known – quite a departure from my pre-Gateway reality. I had before my recovery been quite opinionated. If I did not know something I would always hazard a guess so as not to be perceived as ignorant. I had to smile when he recalled the first time he asked me something about addiction and I replied, “I don’t know … let me check with my sponsor.”

Tim also reminded me of an incident in which I was running late to an AA meeting, parked illegally, and got a ticket. He asked me if I was planning on getting one of my police friends to fix it. After all, even though it was years after my retirement from baseball, I was still a big name in Pittsburgh. But I replied to my son, “No, I screwed up. I need to pay this fine.” When Tim relived this story he expressed a sense of wonderment about his changing father. “I didn’t know this new guy but I loved what I was seeing and couldn’t wait to see what was next.”

He believed what was next was continued sobriety. Tim was quite aware that I had gone five or six months without drinking at times previously and that only a month had passed since I had graduated from Gateway. But his dad radar was telling him something was different. He said he could have bet his life that I had taken my last drink. He was right. The effort I put into my recovery and the drastic changes I was making in my life were beginning to tear down the protective wall he had built between us. It allowed him to promote within him a sense of hope and belief that I would remain sober.

My stay at Gateway and resulting optimism about my future as Sober Sam freed my mind to consider potential options in my personal and professional lives. Among them was reconciliation with Carol. I had prior to my rehab visited her and my then-teenage children at her apartment. I mentioned the possibility of getting back together but she had grown beyond skeptical of my promises, which I had always broken. She replied that if I got help and proved myself with one year of sobriety she would think about reuniting. Nobody knew at the time I was heading to Gateway – that was a spur-of-the-moment decision made after my breakdown at my parents’ house.

After my month-long treatment I visited the kids often but nothing was said between Carol and me about our future together, though I had learned she had been dating other men. So I dropped the idea in part because as a more clear-headed and thoughtful person I felt she deserved some peace and happiness for a change and did not feel it would be right to interrupt the new lifestyle she had adopted. Soon she was living with another guy and I had begun dating as well, though not so often as I had my schedule quite full meeting AA obligations, selling insurance, undergoing special counseling with Twerski, and working with neighborhood children. The latter endeavor would prove particularly rewarding. I assumed for a couple years after leaving Gateway that it would be my career.

Another curve that life might have thrown at me was a return to baseball. I did some serious reflecting on the viability of a comeback. I was only 37 and, heck, some pitchers thrive into their mid-40s. My arm was certainly fresh after five years away from the sport. I competed in an old-timers game in Jacksonville, not just for fun. While warming up I tried to capture my previous form. I lobbed throws during the game for hitters to blast out of the park, as is expected in such an exhibition, but I was not the only person in attendance thinking about a comeback. Another was a scout awaiting the Triple-A game to start who clocked my fastball in the upper-90s during the warmup session. He asked me if I would be interested in returning to the game. Given the million-dollar contracts that had been tossed about during the advent of free agency, a new phenomenon in major league baseball from which I could have benefitted if I had stayed on the straight and narrow, it was a proposal I had to consider. I mulled it over and even discussed it with Twerski.

I ultimately decided that my sobriety was too important to be jeopardized by a return to baseball. My priorities had changed dramatically. They had shifted from what the so-called celebrity lifestyle offered me, which led to dishonesty, self-loathing, and guilt, to what recovery had provided. And that was honesty, pride, and self-respect. Perhaps I could have revived my baseball career successfully. But I simply could not take the chance.

Maybe a return would have been possible had I established a permanent sobriety. It was still too early in the game in 1980. My focus remained entirely on maintaining it and becoming a good man, living a productive life, helping others. My name was still Sam McDowell. But those who knew the old Sam could hardly recognize the new one. They liked what they saw. And so did I when I looked in the mirror.

About the author:

Martin Gitlin is a veteran author and sportswriter. He has had about 150 books published since 2006, including “A Celebration of Animation: The 100 Greatest Cartoon Characters in Television History” (Lyons Press, 2018) with Joe Wos. His “Great American Cereal Book” (Harry Abrams, 2012) soared to No. 1 in both the Americana and Breakfast Book categories on Amazon.com immediately upon release and remained there for several months while his “Powerful Moments in Sports: The Most Significant Sporting Events in American History” earned critical acclaim. Gitlin won more than 45 awards as a sports journalist from 1991 to 2002, including first place for general excellence from The Associated Press for his coverage of the Indians-Braves World Series in 1995. AP also selected him as one of the top four feature writers in Ohio. Gitlin lives in North Olmsted, Ohio.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.

Inspiring story. Thanks, Howard. To Sobriety! I'm grateful that the help was there when i needed it.