Book Excerpt: Under Jackie's Shadow: Voices of Black Minor Leaguers Baseball Left Behind

Plus ICYMI, Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

Law professor and author of sever baseball books, including “God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen,” featured in this space in 2022, Mitchell Nathanson has another fascinating volume for your consideration. Serving as number 23 in our book excerpt series, it is “Under Jackie's Shadow: Voices of Black Minor Leaguers Baseball Left Behind,” (University of Nebraska Press, April 1, 2024, Hardover $32.95, Kindle $31,30).

The blurb at Amazon describes the new work aptly: “The stories of thirteen Black Minor League baseball players during the post–Jackie Robinson era, from the 1960s to the mid-1970s, who were figuratively and literally left behind even as both baseball and the country claimed a newfound racial progressiveness.”

Since he is from Southern California, drafted out of East Los Angeles College and grew up a Dodger fan, I have chosen the chapter contributed by second baseman Chuck Stone to excerpt here. Please find Chapter 13 below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 13: Chuck Stone

It looked

Like half the town

Came in

To watch me get a haircut.

I was originally drafted by the Orioles. I was what you would refer to as a “draft-and-follow” player. I was going to a school called East Los Angeles College when they drafted me. And because they didn’t give me any money to sign I went on to Cal State Northridge where we won the national championship. I was the MVP of the 1970 Division II College World Series.

A draft-and-follow player is when a club gets the rights to you and then they kind of follow you along. And they had until, I believe, sometime in August when they had to sign you. If they didn’t your name went back in the draft for the next season. I didn’t sign with the Orioles. I got right up to that date and then went up to Cal State Northridge and played there. At the end of that season I signed with Detroit. I knew nothing about the Tigers. In LA I grew up a big Dodger fan.

Baseball was always in me; I’m born with it, I guess. I’ve got pictures of me in diapers holding up a baseball bat bigger than me. My family were musicians and as a kid I used to play the drums because of my parents but I’d hear kids outside playing baseball and I didn’t want to come in and practice any longer. I told my mother, I said, Mom, I don’t wanna play the drums anymore. I want to go outside and play baseball. We played every day after school in the street until it got dark.

I joined the Cub Scouts only because I found out the Cub Scouts had a baseball team. Baseball was very big when I was a kid. So much so that a number of guys that I grew up with were drafted in baseball coming out of high school. And that became a goal of mine as well—to get into the baseball draft and become a professional. Derrel Thomas was a neighbor, and he became the first-round draft pick of the Astros.

I grew up in what was called the Crenshaw District. It was a very racially integrated neighborhood. We had Japanese, Blacks, Caucasians, a few Hispanics. And my high school was integrated as well. I was president of my class for three years there. And so, I didn’t have a real strong racial-bias type of situation growing up. I just liked baseball players. I used to like Orlando Cepeda and Don Drysdale, Maury Wills. Jimmy Lefebvre had a real impact on me; he played with the Dodgers and he was Rookie of the Year in ’65. He was a switch-hitter. But Pete Rose was my idol. Another switch-hitter. I patterned my play after Pete Rose. I wanted to be able to play like him and have people call me Charlie Hustle. That was my goal.

Anyway, there were these two Orioles scouts: Al Kubski and Ray Poitevint, and I was on their scout team. Enos Cabell was on that team along with some other guys who eventually went into pro baseball. A number of them played at Cal State Northridge. I think five of the guys that I played with on that scout-league team got a pro contract.

If you watched the movie, Million Dollar Arm, that was Ray Poitevint. He was the scout involved in that—the game show where they looked for a pitching prospect in India. I played for his scout team.

We would play other scout teams. These were teams full of college-eligible guys who were playing on these scout teams. We’d travel down to San Diego, to Arizona. It was all kids who were also being scouted by one team or another. You didn’t get paid for this. It’s still done today. You have guys you’re interested in signing so you take a look at them. They’re predominantly in California. Basically we played on Sundays, some Saturdays.

And then, as I said, I signed as a free agent with Detroit. I decided to drop out of school; left in my senior year. ’Cause like I said, there were kids from my neighborhood or that I played with that were starting to sign. And I started to feel like I was going to be left behind.

A scout by the name of Jack Deutsch called me up one day and asked if I could come up and play with his team on Saturday in a doubleheader. And he says, “Are you sure you can make it to the game?” I said, “Yes, Mr. Deutsch, I’ll be there.” And he said, “Good, because I want to sign you after the game so be sure to be there.” And after the ball game, he took me to his house and I signed with him. I got very little money for signing, I’ll say that much. Nothing to write home about. I was just chomping at the bit for the opportunity.

When I got to Lakeland, Florida, where they assigned me, I couldn’t believe it was A ball. I said, “Are you kidding me?” It felt like the big leagues to me. We played in all the spring training parks where the Major League teams played. The hotels were first-class.

It wasn’t the pit that people make it out to be. For a guy who wanted to play baseball, I was in hog heaven. I enjoyed it a great deal. My manager in Lakeland was a fellow by the name of Stubby Overmire. He was a little guy like I was, and he liked me quite a bit. He gave me an opportunity because he put me in the lineup as lead-off guy practically every day. I believe I played in 130-something ball games and the schedule was 142. Even when I had a bad day, I’d come back and my name was back in the lineup.

But Florida was a bit of a culture shock because I wasn’t accustomed to the Southern drawl, that sort of thing. I couldn’t understand people at first—the drawl of the dialect is a lot different than what I was used to out on the West Coast. But I became a bit of a fan favorite because of the way I played— lots of hustle and a lot of fire. And I think that helped me to get accepted by those people who probably wouldn’t have accepted me, maybe, because of my race.

But I got along with everybody and never had any problems even though there were certain elements of that society in the South that you had to deal with. But for me it was really no big deal. I’m a people person. I try to see the good in everybody.

You know, pretty much everyplace that I played, other than in high school, I was always the first Black player to play there. Myself and John Young—he was my best friend. We grew up together. We played in high school together. He was drafted by Detroit. He later founded baseball’s RBI [Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities] program—he was the first Black player to play at Chapman College. I was the first Black player to play for Cal State Northridge. So I was used to it and really didn’t feel any real pressure. I just ignored a lot of it and kept my head down and kept going, treating everyone with respect.

I would have a lot of telephone conversations with Jack Deutsch during that season in Lakeland and he kind of got me through it. He was telling me what they expected. He’d say, “You play hard. You’re Chuck Stone and if you play like you’re Chuck Stone, that’ll be good enough for everybody.”

I was the only Black player on the team. There were Hispanic players who were Puerto Rican; two of them were my roommates. They didn’t speak much English so I had to learn to speak Spanish. That’s how I became bilingual. And now my wife doesn’t speak English so I speak Spanish fluently. I thought that year was good because I got to play a lot. I grew up mentally, baseball-wise, a great deal. I was disappointed that my average wasn’t higher than it was, though. I hit into a lot of hard outs; those were big parks and guys were running down balls pretty good. So it made it a little difficult to have a good average, yet still I was pleased that my on-base percentage was extremely high. I scored a lot of runs.

But it was a pitcher’s league. It was High-A, the Florida State League, and I faced a lot of tough pitching. But I was able to survive the entire season and it was a lot of fun for me because I just loved playing baseball. We turned two triple plays that year—I played second base. I think we led the league in triple plays!

When the season ended, they didn’t really sit down with you and review your season with you. No, back in those days they didn’t really do that. For the most part you would just hope you got a new contract in the mail and maybe even a little bit of a raise in pay. Even though things were tough for me that year I did get a new contract in the mail. I got moved up to the Midwest League, in Clinton, Iowa. And it was hard enough to try to get a little bit of a raise. But I did and then I played that season for a fellow by the name of Jim Leyland, who went on to have a lot of success in the big leagues. I was his lead-off guy as well.

Clinton, to me, was the same as Lakeland. I didn’t have many racial problems, but I wasn’t a guy who’d go out there intermingling with everybody. So maybe that didn’t hurt. And I had experienced that area before. After my freshman year in college, I played in a summer collegiate league called the Basin League, where I played in Rapid City, South Dakota. I was one of maybe ten Black people in that town, maybe in the state.

And I remember that at one point that summer my hair got really long. Usually I’m close-cropped so I said I gotta get a haircut. And I walked past this barbershop about ten times before I had enough nerve to walk in there to ask the barber, who was white, to give me a haircut. Finally I did and he says, “I’m not too sure if my blades are sharp enough, but come on, sit down, I’ll cut your hair for you.” And I’m in the barber’s chair and—it was so funny—it looked like half the town came in to watch me get a haircut.

Another time I got invited to the Kiwanis Club to be a speaker at their lunch. They asked what it was like growing up in Los Angeles during the time of the Watts riots, back in ’65. They wanted to know what it was like being Black in Los Angeles with the riots going on. I told them, to be totally honest, it was scary. You had to stay inside because there was a curfew in effect. And my parents were pretty strict about me being a decent guy, that sort of thing, so I didn’t go out and loot, none of that stuff. I just wasn’t raised that way. Also, my grandmother worked for the LAPD. She was working records and identification, and I didn’t want to get in trouble because I would hurt my grandmother.

As far as baseball’s concerned, wherever I went—Rapid City, wherever—I was known as a holler guy. They call them holler guys—always chattering, that kind of stuff. Also, I used to like to whistle a lot. Whenever I walked around the town or had to go someplace, in Rapid City or wherever, I’d have kids following me around the town saying, “Hey, are you the Whistler?” And I say, “Yeah, I’m the Whistler.” “Can you whistle for us?” That’s how I got the nickname, the Whistler—from the kids. And I’d chatter: “Hey, batter batter . . . strike ’em out!” And then I’d whistle. And so the little kids would hear that, and then all of a sudden when I’d whistle, they’d whistle back. So the announcer would say, “Now batting for the Rapid City Chiefs, number six, the Whistler, Chuck Stone.” And everybody starts whistling. I was pretty well accepted in that town, especially after I got the nickname.

After that season I got released from the organization. I was told they had to make room for a guy named Tom Veryzer, who was their number-one draft pick. So that’s kind of the way it goes. I was a little bit in shock, but I didn’t have high numbers—the batting numbers—I guess that they were looking to have. So that was that. But some years later they offered me a job as Minor League manager in rookie ball.

And I actually signed a contract with them. But I never got to manage. I was technically the first Black manager in the Tiger organization, and I was supposed to go to rookie ball in Florida. But during that year I got divorced from my first wife. And I would’ve had to be in Florida for a long time. And she wouldn’t allow my kids, who were ten and eleven at the time, to come visit me there. They really wanted to come but she refused to let them go. So I had to tell Detroit that I wasn’t going to take the job because I didn’t want to miss my kids over the full summer. So I had to walk away from that. I didn’t want to hurt them. I said, I’ll find another baseball job somewhere down the line, but I really want to be with my two children.

I let some years go by because I wanted to make sure I had the visitation, that kind of stuff. I ended up working in insurance. I mentioned John Young, my best friend growing up—I was friends with him since we were both fourteen years of age. One night we were talking and he said, “You know, we used to play in all these parks in LA when we were growing up. There were all kinds of community leagues and stuff.” He says, “I pass these same parks today, Chuck, and they’re all empty. Nobody’s playing baseball. I wanna do something about that.” This was in the 1980s. “I want to revive baseball,” he said to me. Then it just hit him: “We’ll revive baseball in the inner cities,” and that became the RBI program that baseball runs today.

It wasn’t easy. In LA we’d primarily go to inner-city parks, announce that the RBI was coming there and conducting tryouts for teams. All we had were caps and T-shirts. And a certain amount of kids would show up. Parents would show up and we’d ask the parents to get involved, be coaches of the team, you know, dads who had some level of baseball acumen. And it just kind of grew from there.

Along with the baseball there were programs where they would have kids tutored to try to get their grade point averages high enough to where they would qualify for scholarships. A lot of scholarships were given out to some of these kids. And then John gravitated to where RBI had girls’ softball and that just blew up for rbi. Because a lot of girls had nowhere to play. John was pushing these girls to do better because that would get them the recognition from the college coaches and give them scholarship opportunities also.

John would go out soliciting big league players to help him out with the funding. The first guy that really came through for him was Kevin Brown. He donated a million dollars to John for the RBI program. That got him off the ground. And then Major League Baseball caught wind of it, and went Hey, this could be a big deal for baseball. And they donated a lot of money to the RBI program.

Around this time, ’87 or ’88, a friend of mine, Dennis Lieberthal—his son Mike played in the big leagues— recommended me to be a scout for the Tigers. Dennis was a scout with Detroit and after I’d stopped playing in ’72 I’d refer guys to him. I referred a number of guys to him that he signed and eventually he helped me to get a scouting job with the Tigers. But then I started thinking to myself: Why don’t I give being an agent a try?

I thought I could be a good one because I know what baseball players are up against and what they need to do. I used to tell my players, “Look, you got any problems with your manager or other players or confrontation with the front office . . . you don’t go complaining to them. You let me stand in between the two of you and I’ll take care of the problem.”

I wanted to become a player’s agent. You know, you gotta make money to survive, but I was just trying to influence and get my players to the big leagues. I was able to acquire a number of good players. One of them was a kid named Covelli Crisp. I was his agent when he signed, initially. He became Coco Crisp and played in the Major Leagues. When he was playing rookie ball in Johnson City the kids there thought it was interesting to call him Coco Crisp, you know, after the cereal.

I did that until I got a job with the Houston Astros in 2006. At that point I had to stop doing the agent thing because I’m now working for management. I got the Houston job because a good friend of mine, Enos Cabell, was working for them. And they got into a little bit of a problem racially during the 2005 World Series. They were playing the Chicago White Sox and the NAACP was boycotting them outside of the stadium because they were the first World Series team in decades to not have a single Black player. And so the owner got kind of offended by that and he said I have to do something about that because I’m not a racist. His name was Drayton McLane and I liked him a lot.

So Enos Cabell said to him, I know a guy who could help us solve that problem. This guy’s name is Chuck Stone. He lives in LA. He could go into the Black community. He can also go into the Hispanic community because he’s bilingual. So they asked me to come to the winter meetings that were in Anaheim that year.

So I went to the Anaheim Hilton. They interviewed me, told me what the situation was. They said they would like for me to find minority players in the inner city. I told them it’d be no problem. I’d love to do it. So they hired me and that was my objective, but I was going to look at everybody.

I ran the Astros’ scout team from 2006 to 2009. In three years of playing in the scout league against the other scout teams, we lost two games. We beat everybody up pretty bad. And my scouting director, he came out to California to watch us play.

And he hears all this cheering and all these guys—my Astros—running the bases all the time. So he came down to the field where we were. He said, “Chuck, what the hell is going on here?” I said, “We just keep running these guys off the field.” And he sees us scoring runs. And I said, “Well, I’m going to keep this job or I’m going to lose it. We’ve got some n——s on this team. We’ve got some Mexicans and we got some hard-ass white boys and we come every day to kick your blankety-blank.” And he says to me, “Well damn Chuck, why isn’t every club that way.” So we hit it off real good after that. ’Cause he saw that I wasn’t just . . . because I was hired to find blacks and minorities. And I thought I found some pretty good ones, but the whole deal was, we didn’t want to look like we were prejudiced in one way. At least that’s the way I saw things. So that’s what we did.

But my supervisor was very racial. I don’t care to mention his name, but he told me to my face one time that he would never sign a Black ballplayer. And then I saw what the problem was for the Astros. They had a lot of kids who could’ve signed with the Houston Astros during that time, but they weren’t being scouted correctly. When I was growing up, heck, the Astros were loaded with Black players, and they’d beat the hell out of you. When I was playing in the Florida State League, they had a team in Cocoa Beach and, man, the Astros had some studs, they could do a number on you. So I was surprised when I found out that they didn’t usually sign Black players anymore because of this area supervisor.

For me it was an eye-opener because I always said, Woah, the Astros, they’re loaded. They always had a lot of Latin players in their rotation, mixed in with a lot of white players who were good prospects. But this supervisor . . . it’s just unfortunate that he didn’t pull the trigger on those prospects because we had some guys on our scout team that he just refused to come out and scout and co-sign the deal. Because you know, when you turn a guy’s name in as an area scout, the supervisor has to cross-check it. He has to agree with it. I had a lot of trouble with him in that regard.

And then they fired me. I was told I’d have a job for life. That’s what I was told when they hired me. But they let me go. Eventually the supervisor got fired too.

When I look back on my days in the Minor Leagues, it’s the friendships I remember most. For the most part, I look at it as more of a positive than a negative. I take a little pride in it all. I wear my Detroit stuff whenever I can. People, they might think I’m a little weird out here in California: “What’s that D stand for? Dodgers?” I say, “No sir, it stands for Detroit.”

I sometimes dream in baseball but those dreams are kind of unfulfilled. And so I try to inspire the youngsters I work with now. I’m too old to play, but I try to inspire them, tell them what it’s like in the Minor Leagues, what you need to do to get there, and what scouts are looking for. It gets them to play a little bit harder to try to reach their goal. The goal I was never able to reach.

About the author:

Mitchell Nathanson is a professor of law in the Jeffrey S. Moorad Center for the Study of Sports Law at the Villanova University School of Law. He is the author of several books, including Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original (Nebraska, 2020), God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen, and A People’s History of Baseball.

ICYMI:

Former Dodgers great Justin Turner is headed to Toronto on a one-year $13 million contract, with “$1.5 million in roster and performance bonuses.” He’ll serve as the Jays primary designated hitter, and possibly getting into some games at first base and third base, as was the case in Boston in 2023. Turner hit .291/.361/.497 through August 27 last year, slumped a bit in September and finished at .276/.345/.455 with 23 homers and a career-high 96 RBIs. He can still hit. And the Dodgers will see him in Canada April 26-28.

Since leaving the Dodgers after the 2020 postseason in which he hit .382/.432/.559, Joc Pederson has played for the Cubs, Braves and Giants. He’ll be Arizona’s DH in 2024. And I’ve got news for you: With the addition of third baseman Eugenio Suárez and Dodgers-snubber Eduardo Rodriguez, the DBacks are much improved from last year’s National League pennant-winning club. It’ll be a two-team NL West race from start to finish. San Francisco, San Diego and Colorado aren’t even trying to be competitive, and as a result, they won’t be.

Former Dodgers left-hander Alex Wood has agreed to terms with the A’s. For some reason. While I imagine he could have gotten a minor-league deal with a better team, the East Bay will serve as a reasonable facsimile.

Shohei Ohtani accepted his American League Most Valuable Player Award in New York over the weekend, delivering a speech entirely in English, thanking the Angels, the Dodgers and his fans in Japan. Read the transcript here.

A handful of little transactions to tell you about. Los Angeles has signed reliever T.J. McFarland, infielder Kevin Padlo and right-handers Kevin Gowdy and Michael Petersen to minor-league contracts, with invites to Spring Training.

And New York Congressman Adriano Espaillat has begun a campaign to honor Roberto Clemente with a commemorative coin in celebration of his “impact on the ‘Latinization’ of baseball and his commitment to helping others.”

Media Savvy:

David Adler explains “how the Dodgers can unlock a next-level Paxton” at MLB.com. Mark me down as skeptical.

The always great Jayson Stark answers a mailbag question about who might be a future unanimous Hall of Fame inductee. And a number of other interesting HOF bits of information, at the Athletic.

Also at the Athletic is a story by Ken Rosenthal about age falsification and identity fraud involving young players in the Dominican Republic. And Ken has a piece about why he isn’t buying “the A’s grandiose Vegas plans” that is worth your attention.

While this isn’t a baseball centric topic, the art buff featured covers all sports during their respective seasons. And he’s incredible. Please see “You Saw Jason Kelce. This Guy Saw ‘The Feast of Bacchus.’ With his Art But Make It Sports social media accounts, LJ Rader connects the drama and pathos of classic artwork to viral moments in sports. And no, he’s not using A.I.” by Scott Cacciola at the New York Times.

Baseball Photos of the Week:

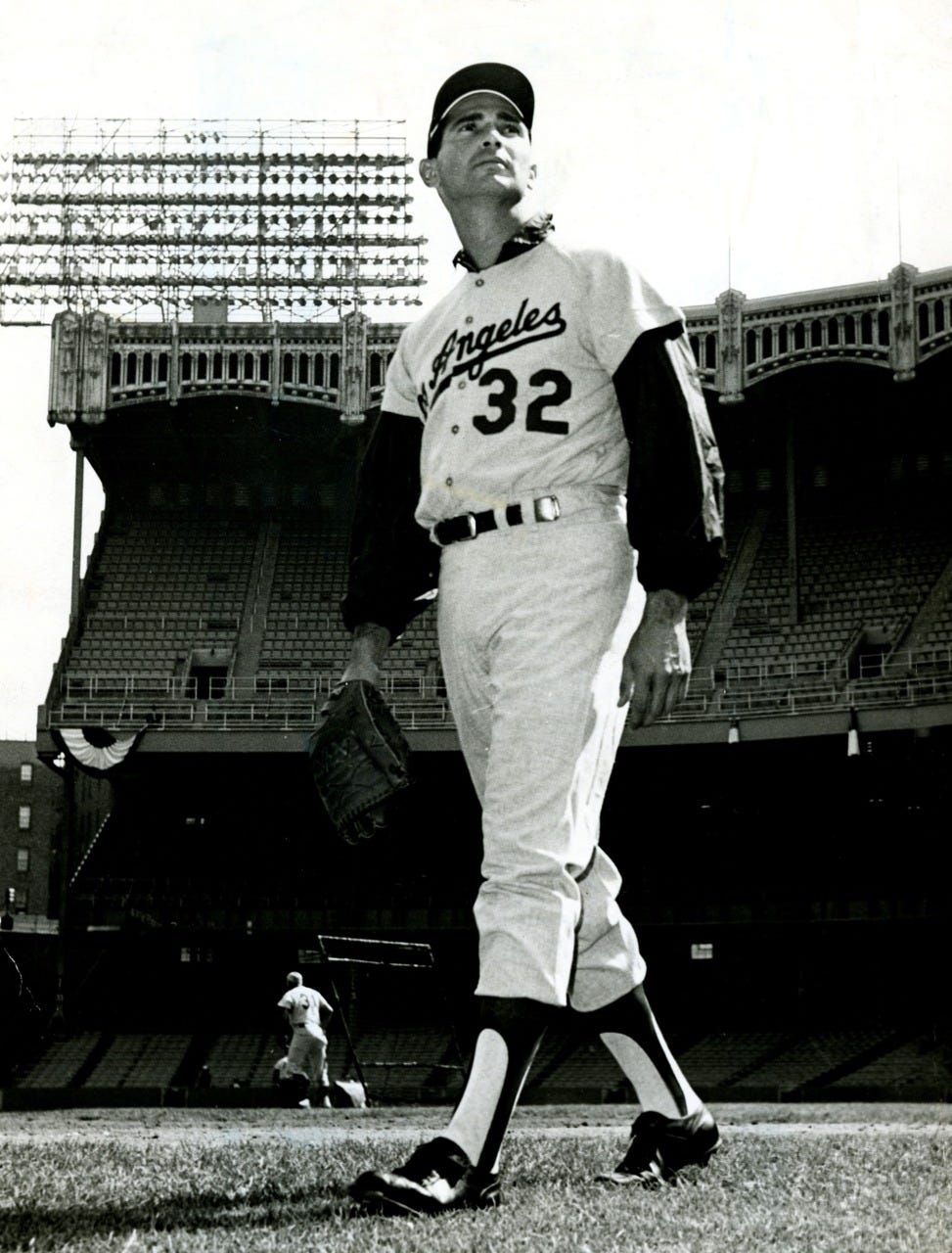

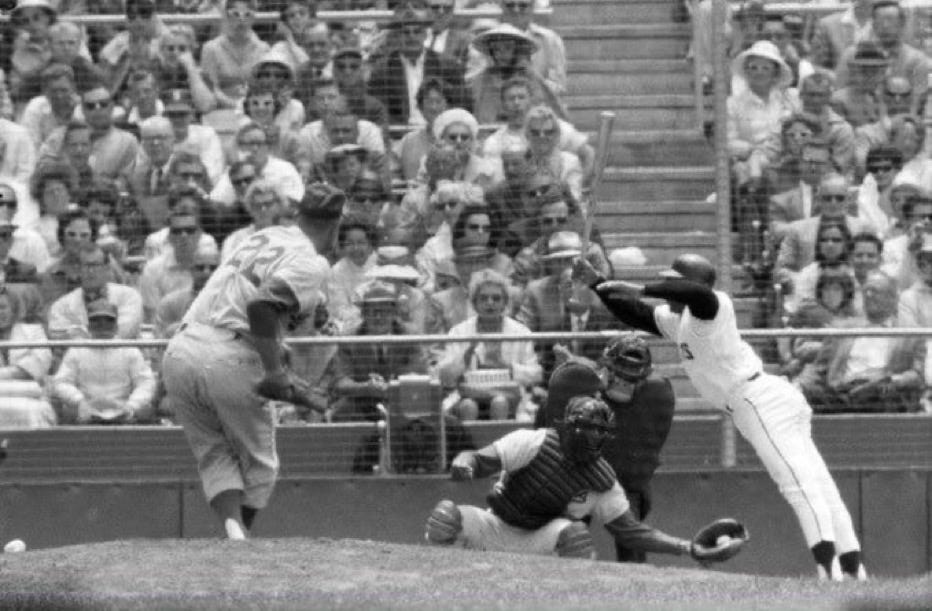

Sandy Koufax, October 1963.

Johnny Padres and Willie Mays.

Oscar Gamble.

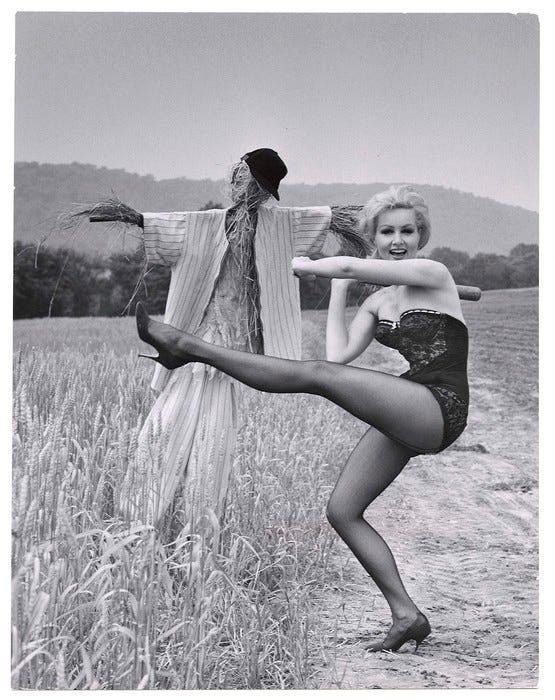

The archived Life Magazine caption reads: “Actress/dancer Julie Newmar warming up for her devil's role in the musical "Damn Yankees” next to a scarecrow in baseball togs at summer theater.” But I imagine she appeared as Lola, with the Ray Walston part going to a player to be named later.

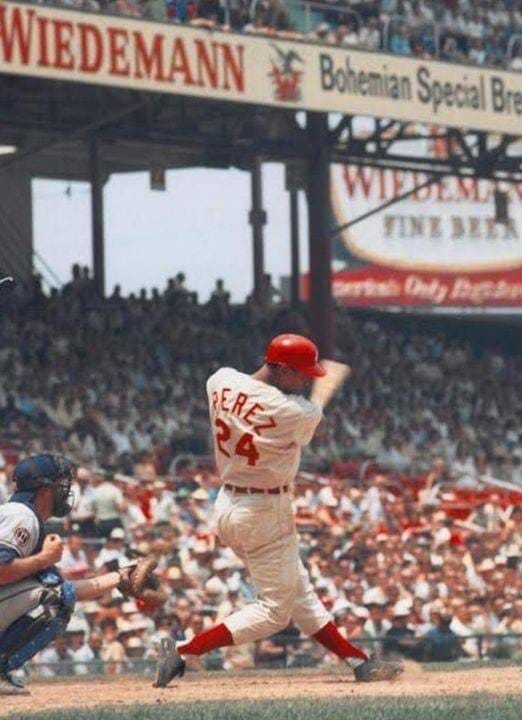

Tony Perez.

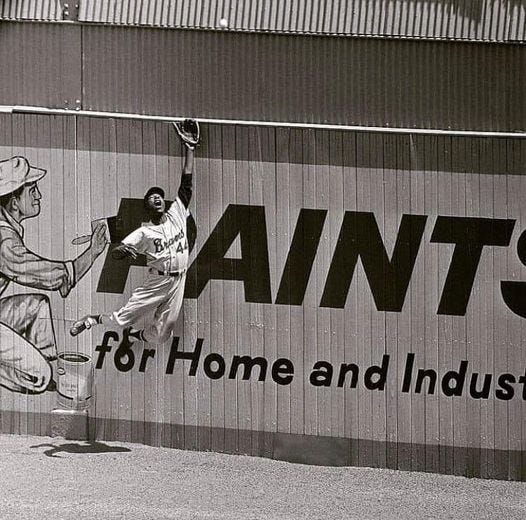

Hank Aaron.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.

Good chapter, good story. And "Stubby Overmire"!

I would like to pay the $50 for upcoming season with a gift card. Can your administration provide me with an email so I can send the card number.