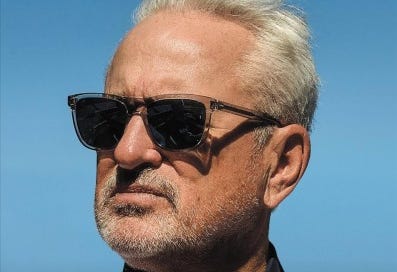

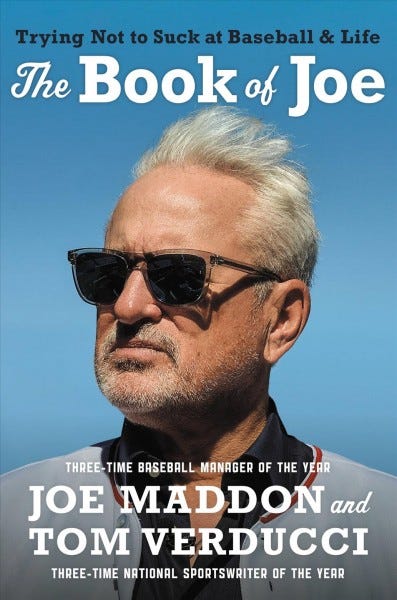

I’m excited about this one, folks. With number 15 in our book excerpt series, I turn to the former Angels, Rays and World Series champion Cubs skipper, and “The Book of Joe: Trying Not to Suck at Baseball and Life,” by Joe Maddon and Tom Verducci, (Twelve Books, October 11, 2022, $29.99 Hardcover, $14.99 Kindle).

More accurately, “The Book of Joe” is a baseball book by Tom Verducci. In collaboration with Joe Maddon. It’s Maddon’s quotes interspersed throughout; not him writing in first person. It’s Maddon’s thoughts on all kinds of things, obviously very much including managing baseball. And I think it’s fair to say that “The Book of Joe” is about the making of a big league skipper; this particular, thoroughly interesting big league skipper.

Included in the volume are the thoughts of several managers, with Joe Torre, Bruce Bochy, A. J. Hinch, David Ross, Dusty Baker, Alex Cora, Brian Snitker and Dave Roberts, who is featured prominently, among them. I considered excerpting a Roberts section about the Dodgers’ 2019 National League Division Series loss to the Nationals, but stopped myself, screamed “too soon!” and didn’t.

Instead I chose an especially philosophical chapter — Chapter 10, “Aim High” — in which Michelangelo is mentioned seven times, and quoted once. John Wooden, Albert Camus and Alan Greenspan are also quoted in the chapter, which follows below.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

After the excerpt you will find the usual Off Base sections, ICYMI, Tweet of the Week (which is a good one), Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

Chapter 10: “Aim High”:

The Devil Rays lost 101 games in Maddon’s first year there and ninety-six the next. By the time they assembled for spring training in 2008, they had a new name—just the Rays—and a stunning new look. Of the twenty-five players on the 2006 Opening Day roster, twenty-two were no longer in the organization. Dukes and Young had both been traded. Professionals in the mold of Davey Martinez had been brought in: outfielder Cliff Floyd, first baseman Carlos Peña, infielder Eric Hinske, pitcher Edwin Jackson, and, by way of Minnesota in the deal for Young, shortstop Jason Bartlett and pitcher Matt Garza. First-round picks Evan Longoria, a third baseman, and David Price, a pitcher, were major leagues ready without the earmarks of an entitlement program that had marked the Devil Rays system.

The Rays, Maddon believed, were ready to smash conventional wisdom. That is, if his players believed they could do it. A few weeks before spring training began, he composed a letter to them. In part it read:

We accept conventional wisdom as true, especially if it blends with what we already think. It is the “raft” that supports the world as we see it. We are in, we agree. Who will benefit the most with the acceptance of this “conventional wisdom?” Does it in fact stand up? Is it actually true and worthy of our support? Do we really know, or are we repeating what we have heard?

Our view of the baseball world is different than say, the Yankees, the Red Sox, etc. We play by the same rules, but at the same time, we do not. The sameness occurs on the field, and that is up to us to make sure that we stand toe to toe with them in the execution of the game. The preparation. The desire to be the best. The will to win.

Conventional wisdom tells us that we have no chance based on their economic base. They have the ability to spend countless dollars to arrive at the top. We need to find another path. A path that lies below the surface.

We have to do all the little things better than anyone else. We are in the process of creating the “Ray Way” of doing things. Conventional Wisdom be damned. We are in the process of creating our own little world. Our way of doing things. The Ray Way. To those of you who feel as though this sounds “corny” wait a couple of years and you will see how corny turns into “cool” and everyone stands in line to copy our methods.

Shortly after sending that letter, Maddon was riding his bike on his usual jaunt along Birch, Rose, and Bastanchury in Brea and Fullerton, California, when a particularly clear thought floated to the top of his mind: Nine equals eight.

If nine players played hard for nine innings every night, he thought, then the Rays could be one of eight teams in the playoffs in 2008. And maybe even the World Series.

It made sense to Maddon. It sounded like lunacy to everybody else. Tampa Bay was coming off a ninety-six-loss season. Two hundred and twenty-nine teams in baseball history had lost ninety-six games or more. Only one of those previous 228 losers had gone to the World Series the next year, the 1991 Atlanta Braves.

Maddon liked the combination of power and simplicity in his equation. He rolled it around his head some more.

Nine more wins from the offense, nine more wins from the defense, and nine more wins from the pitching staff equal twenty-seven more wins, which should be enough to get in the postseason. Add the digits of twenty-seven and you get nine. And nine equals eight.

Neanderthals used cave walls. Ancient Egyptians used papyrus. Jackson Pollock turned household alkyd paints into eternal art. Maddon’s medium is the T-shirt.

Maddon has a sloganeering tradition that dates to the Angels’ minor league system in the 1980s, when he handed out T-shirts that read, “Every Day Counts.” As manager, starting in 2006 with “Tell me what you think, not what you’ve heard,” every year Maddon likes to come up with a slogan that eventually finds its way onto your basic cotton T. In 2008 the slogan was “9=8,” which the Rays began sporting early in the season. Much more than a gimmick, such themes are mortar to Maddon.

“When you are with an organization like the Rays, where there is no established identity, this kind of repeated language helps that identity that you want to form,” he says.

Maddon stood before his players before the spring games started and told them, “I want you to play the same game. I don’t care if it’s March fifteenth or June fifteenth or, yes, October fifteenth. Play hard. We will play hard in spring training and take it into the season.”

The Rays took his message to heart—and to the New York Yankees. On March 8 at George M. Steinbrenner Field in Tampa, a Rays utility player named Elliot Johnson broke from first base for home on a ninth inning double with Tampa Bay leading 3–1. As New York catcher Francisco Cervelli caught the throw from the outfield, blocking the plate, Johnson lowered his shoulder into Cervelli.

“Boom!” Maddon says. “He absolutely pancakes Cervelli. The ball flies out. Run scores. We win the game. Cervelli breaks his wrist.”

Word reached Maddon after the game that Yankees manager Joe Girardi was incensed over Johnson plowing into Cervelli.

“I’m in the manager’s office, and I’m getting word from the press that Girardi’s upset,” Maddon says. “I thought I needed to know why he’s upset. Did he consider it a dirty play, or did he think you shouldn’t do it in spring training? I needed that answer. There’s a big difference, and there would be a big difference in how I would respond.

“If he thinks it’s dirty, well, that’s just his interpretation. We can disagree. But if it’s the other thing ...”

One of the writers in the room explained to Maddon that Girardi said the play was “uncalled for” in a spring training setting.

“The moment he said that—that you shouldn’t do it in spring training because you don’t want to get anybody hurt—man, that opened up a whole can of worms for me,” Maddon says. “I went off. We’re trying to ascend in this division. This idea that it’s OK if the game is played in the regular season but not in spring training didn’t sit well with me. Not at all.”

Told of Girardi’s view that spring training should be played with less effort and intensity, Maddon shot back, “I never read that rule before. ... We play it hard, and we play it right every day.”

“A few days later, we’re playing the Yankees again,” Maddon says. “Jerry Crawford, the home plate umpire, has a meeting before the game at home plate with Girardi and me. I go, ‘We’re good, man. We just want to play baseball.’ I could tell Joe was upset.

“Jerry goes, ‘We can’t have it. I’m telling you, we can’t have it.’ I go, ‘Jerry, you’ve got nothing to worry about.’ But I knew Joe was not pleased.

“Game starts. Shelley Duncan of the Yankees hits a line drive off somebody’s glove and tries to stretch it into a double. There is no way any runner is going to go to second under those circumstances—no way— but Shelley knew this was his opportunity to get revenge. Shelley comes in spikes high into our second baseman, Akinori Iwamura, at second base. He spikes him in the right thigh and knocks him down. It was a dirty play and I said so. All hell breaks loose. Jonny Gomes is in the middle of the melee just picking guys off the pile—I mean picking them up and tossing them away.

“Now I will tell you this: those two moments—the play by Elliot Johnson and the way we came together after the Shelley Duncan slide— accelerated us out of the chute. Icing on the cake was a fight we had later with Boston. But when Shelley came in spikes high and when those writers told me Girardi said you shouldn’t play like that in spring training, we were on our way. It was validation. Everything I had been telling them, they were putting into practice.

“We knew the Yankees had had their way with us. We knew we were going to have to take it from them. They weren’t just going to give it to us. But that day at Al Lang Stadium was like Bizarro World. It was turned upside down. We were taking it from them. Had the Yankees chosen not to go after us, then nothing at all would have happened. I am absolutely convinced that set us on our way.”

The Rays finished spring training 18-8, a club record for wins and the best record among all thirty teams. They went 15-12 in April, followed by 19-10 in May. By July 6 the Rays led the American League East by five games. But suddenly they collapsed. They lost seven straight games heading into the All-Star break, getting outscored 45–13 and falling into second place.

On July 18, before the first game after the All-Star break, a home game against Toronto, Maddon called a team meeting. This was one of the three planned meetings Maddon will hold during a season, all to reinforce a positive message. The first meeting is held as spring training begins. His second meeting is held just before or after the All-Star break to refresh the message to his team. The third takes place before the start of the postseason. Otherwise, Maddon hates team meetings.

“How does the line go? ‘The beatings shall continue until morale improves,’ ” Maddon says. “In the big leagues, I’ve been around managers like Scioscia and Marcel and Terry Collins who have had meetings. Even one time Billy Bavasi, the GM, came down during a bad moment, and, if I remember correctly, he was airing us out.

“And it’s really hard. You have to understand, it sounds like it’s such a good idea in your head before you do it, but it’s rare that it actually has the impact you’re looking for.

“And I would sit there on the floor during major league team meetings by the manager and I would shake my head because hey, I played in the minor leagues, at least, but I’m an athlete. I played a lot of games, for a lot of teams. And some really bad teams like the Scranton Red Sox, my first year up there, I think we won, I don’t know, 8 and 32, something horrible. So I’ve been on that side—rarely—but I’ve been there.

“So when a coach sits you down and wants to start beating you up verbally, it rarely works. It makes the coach feel better. It makes the deliverer of the message feel better and getting it off his chest. Not necessarily the players.

“I’m here to tell you, it was rare that I was involved in a meeting that there was any kind of substantial boost to our morale, our play. It’s just a venting procedure for the guy that’s doing the yelling. I really believe that.

“The other thing is, usually with a team that’s losing there probably has been a lot of negative backlash about the team, negative things said about you as a manager. Most of the time it’s not true, but it’s something you’ve got to wear it. You got to wear it.

“That’s another reason why I don’t like team meetings: because it always sounds like you’re making an excuse.

“Most meetings, I’d say ninety-seven percent of them, are not necessary.”

On the Rays’ first day back from the 2008 All-Star break, Maddon gathered his team for a meeting in right field at Tropicana Field. It is his policy not to conduct team meetings in his team’s home clubhouse. Why?

“It poisons the room,” Maddon says. “To show up at home every day and then have it be this negative room and a lot of yelling and screaming and throwing of things and name calling? Not good.

“The other part about that, the thing I learned from in the past, all these other major league meetings I was in? A lot of them were in a home clubhouse. Home clubhouse after a loss. Two things about that: You just lost. You feel like crap already.

“And two, you’re at home. This is your living room. This is supposed to be the warm fuzzy you need to go to when things are bad to get your act straightened out. If it’s going to be a blowup, folks, if at all possible, remember two factors: do it on the road, and do it after a win. That’s the best time to make your point.”

Gathered in the outfield, Maddon told his players a story about the 1983 Baltimore Orioles. They had two seven-game losing streaks, one in May and one in August. Each one knocked them out of first place.

“Do you know what they did?” Maddon told them. “They won the World Series.

“Do you really think we’re going to roll through this without hitting some bumps? Treat this moment with respect because this doesn’t happen every year—the chance to win the World Series. For you young guys, it’s happening for the very first time, so treat it with respect because it doesn’t often come along. For you veterans that maybe have been through this before, treat it with respect because it might be your last chance.”

That night the Rays trailed Toronto, 1–0, two outs into the seventh inning. Hinske drew a six-pitch walk from Blue Jays right-hander A. J. Burnett. Ben Zobrist hit the next pitch for a home run. Tampa Bay won, 2–1, and regained first place. The team held first place the rest of the season, though not without Maddon calling one of those rare fire-and-brimstone meetings that he detests.

The Rays were in Kansas City. It was a Saturday night, and only eight days after Maddon’s inspirational 1983 Orioles speech. Tampa Bay had beaten the Royals, 5–3, but Maddon seethed about how they’d played. The baserunning had been lethargic. Second baseman Akinori Iwamura, for instance, had jogged from first base on a bloop double by B. J. Upton, costing himself a chance to score.

“We made all kinds of mistakes,” Maddon says. “We weren’t running hard, mental errors... we were doing well, so we thought we were hot stuff. I went off.”

As a steamed Maddon walked back to the clubhouse, he said to bench coach Dave Martinez, “Get ’em in here. Right now.”

The meeting was brief, but hot. For the first time in three years, Maddon ripped his team for not hustling. “I’ve seen teams miss the playoffs by one game!” Maddon told them. “And here you are up by one game and you’re not playing hard!

“We haven’t done shit yet, and if we keep doing this, then this wonderful beginning we’ve had to this year is going to end up hollow. So for those of you who think you’re hot shit, know one thing: you’re not! And if we don’t get our shit together from here on out, it ain’t going to happen.”

Says Maddon, “It was one of those times when you talk and cry at the same time a little bit. You’re crying because you can’t control your emotions. I was a little bit out of control. I was really loud. I don’t think my message was long or elegant, by any means. I’m screaming. I mean, it’s to the point where I’m yelling, crying, and running out of breath at the same time. I don’t think it took more than three or four minutes, but I did find out—I didn’t ask, but I found out, you always do—that a lot of guys thought that was perfect. We needed that kind of a thing.”

As reliever J. P. Howell said, “From then on, every game was important to us. We weren’t going to give anything away. I think that’s when we realized we could really do this.” The Rays went 36-23 after that meeting. They finished 97-65 and won the division by just two games.

Maddon had succeeded in changing the culture. The Rays played hard, they expected to win, and they did not reek of entitlement. It had happened not because Maddon forced discipline upon the team but because of the relationships he’d built and how he trusted his players to be guided by self-discipline. Anybody who walked into the Rays’ clubhouse not only felt that vibe but also could read about it in giant letters plastered on the walls there, courtesy of placards that Maddon ordered:

DISCIPLINE YOURSELF SO THAT NO ONE ELSE HAS TO

—JOHN WOODEN

INTEGRITY HAS NO RULES

—ALBERT CAMUS

RULES CANNOT TAKE THE PLACE OF CHARACTER

—ALAN GREENSPAN

Not posted, but at the root of the same philosophy, was this pearl from Maddon to his Rays: “The more freedom given, the greater respect and discipline returned.”

Maddon also knew he had to step in if the self-discipline broke down. On August 5, B. J. Upton did not hustle down the line when he hit a grounder back to the pitcher in the eighth inning with the Rays up 8–4. Maddon benched him the next game.

“I didn’t run it out,” Upton said. “But it’s over, done with, you move on. Learned a lesson.”

Eight days later in Texas, Upton failed to run hard again on a double-play grounder that ended the sixth inning. So much for Camus. Maddon motioned for Upton to return to the bench rather than to his position in center field. He pulled Upton from the game and replaced him with Justin Ruggiano.

“If we’re going to be a really good organization, it has to permeate the entire group,” Maddon said. “I’m not just talking about the major league team. I’m talking from rookie ball all the way up to Triple A. So I hope that our minor leaguers read about all this also, because I want that message sent to them, too. That’s how we play.”

Upton sat out one game. He returned August 17, the night Maddon ordered an intentional walk to Josh Hamilton with the bases loaded. The Rays were leading, 7–3, with two outs in the ninth inning when Maddon told pitcher Grant Balfour to walk Hamilton, choosing to give up one run rather than risk a game-tying grand slam. Maddon then replaced Balfour with Dan Wheeler, who promptly struck out Marlon Byrd to seal the win. (Maddon reprised the gambit in 2022 with the Angels. He intentionally walked Corey Seager of Texas with the bases loaded while trailing—and won the game. No other manager in the previous twenty-four seasons ordered a bases-loaded intentional walk once.)

Maddon managed the Rays unconventionally. He used a four-man outfield and a five-man infield. He brought in left-handed relievers to face right-handed batters, and vice versa.

His team stole more bases and bunted the least of any team in the majors. His players ran into more outs on the bases than all but one team. It was not because his players were reckless. It was because Maddon encouraged them to be bold. Maddon never liked the bromide “Don’t make the first out at first base or third base” because that is a negative thought that encourages conservatism on the bases.

“The proper mindset is, ‘Get to third base with less than two outs as often as possible,’ ” Maddon says.

The Rays ran all the way to the World Series, where a loaded Philadelphia Phillies team stopped them in five games. Maddon responded to the World Series defeat in a thoroughly Maddonian way: with optimism and a paraphrase of a quote from an 1858 collection of essays by the poet and polymath Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

“The mind, once expanded to the dimensions of larger ideas, never returns to its original size,” Maddon said.

He knew his players were better for the experience. They had expectations now of success. The culture was changed. The Rays had an identity. From that formative season of 2008 through 2021, during which time Maddon and Kevin Cash, his former player, each managed seven seasons, the Rays posted the fourth-best winning percentage in the majors, behind only blue blood franchises the Dodgers, Yankees, and Cardinals.

Maddon helped launch one of the most shocking turnarounds in baseball history. A franchise that had never had a winning record, that had never won more than seventy games, suddenly won ninety-seven games in 2008— a thirty-one-win improvement over the previous year—and did so with the second-lowest payroll in baseball. The Rays finished eight games ahead of the Yankees with a payroll that was one-fifth of what New York spent.

Less than a month after the World Series, Maddon was honeymooning in Rome with Jaye when his phone rang. It was nine o’clock on an oil painting of an Italian evening, and the two of them were well into a bottle of red at a restaurant not far from the Spanish Steps. There was good news on the line: Maddon had been voted American League Manager of the Year—and by the largest margin ever. He’d received twenty-seven of the twenty-eight first-place votes.

On their trip Maddon and Jaye also sampled Florence, Prague, and London. The highlight for Maddon was being in the presence of two of the greatest works of Michelangelo, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and his sculpture David.

“Those may be the two most religious moments you can have as a human being,” Maddon says. So inspired by Michelangelo’s work and life was Maddon that he sat down to write a letter to his newly crowned American League champion Rays:

The greatest danger

For most of us

Is not that our aim is

Too high

And we miss it,

But that it is

Too low

And we reach it.

MICHELANELO (1475–1564)

Maddon then liberally quoted from Wisdom of the Ages by motivational speaker and author Wayne W. Dyer, a book he had read recently. Maddon was so impressed by Dyer’s insights that in a 2009 interview he included Dyer among his three ideal dinner guests. The other two were Branch Rickey and Mark Twain. Rickey, the innovative baseball executive with the Cardinals, Dodgers, and Pirates, is Maddon’s “administrative idol.” And Twain? Maddon admires Twain’s “zest for life.” He regards Twain as an especially keen observer of human nature who captured our complexities and nuances with a razor-sharp wit and the simple turn of a phrase.

Michelangelo is one of sixty intellectuals whose teachings Dyer explores in Wisdom of the Ages. Fresh off his trip to Italy, Maddon quoted from the book to his players:

The world is full of people who have aimed low and thought small who want to impose this diminutive thinking on any who will listen. The real danger is the act of giving up or setting standards of smallness for ourselves with low expectations. Listen carefully to Michelangelo, the man who many consider the greatest artist of all time.

Michelangelo’s advice is just as applicable today in your life as it was in his, over five hundred years ago. Never listen to those who try to influence you with their pessimism. Have complete faith in your own capacity to influence others with your attitude of aiming high and achieving it.

Aim high, refuse to choose small thinking and low expectations, and above all, do not be seduced by the absurd idea that there is danger in having too much belief. In fact, your high expectations will guide you to heal your life and to produce your own masterpieces.

It was one of Maddon’s core tenets for changing the culture in Tampa Bay. Concluding his letter, Maddon continued to aim high and asked his players to do likewise. He wrote:

I have been to Italy and have seen both the Sistine Chapel and the statue David. Michelangelo’s level of skill and talent were indescribable then and now.

I believe you are all artists in an athletic sense. Very few people are able to perform daily with your level of skill and consistency. There are different levels of success within our profession. My wish is that you all understand to participate is merely the first goal, and one to be passed very quickly. The ultimate goal is to play the last game of the year which is more the result of teamwork over individual achievement. This requires dedication above and beyond. Kind of like walking through the Vatican for four-plus years and spending much of the day lying on your back while painting a ceiling that you had no idea would be talked about for the rest of time.

Hopefully this piece will stir a bit of thought within you. We all have to apply total dedication to our goals. We may not cause people to talk about us for the rest of time, but I would settle for this next century.

THE FOUR BASIC HUMAN NEEDS:

1. to live

2. to love

3. to learn

4. to leave a legacy (let’s leave ours)

ICYMI:

Yep, you heard correctly. Eric Burton botched the national anthem prior to Game 1 of the 2022 World Series Friday night in Texas.

Former Dodger Skip Schumaker has replaced former Dodger Don Mattingly as the manager of the Marlins, God bless em. If this marks the end of Mattingly’s career as a big league skipper (and I think it does), he finishes with an 889-950 record, good for a winning percentage of .483. Or bad for.

David Stearns has stepped down as president of baseball operations in Milwaukee. And while he said all the right things afterwards, my assumption is that the Brewers big boss left to work for an owner who actually wants to win, instead of Mark Attanasio, who simply can’t be bothered.

And sadly, Roz Wyman, the Los Angeles City Council member who was as arguably responsible for bringing the Dodgers to town as anyone west of the Mississippi, has passed away at the age of 92.

Tweet of the Week:

Media Savvy:

Photographer Robert Gauthier, who is also a fine writer, has a lovely story titled “Capturing old-time baseball with a 113-year-old camera” at the Los Angeles Times. Dateline: “Twin Peaks, Calif.”

For more fine baseball writing we go to Tyler Kepner, and a piece about the 1980 National League Championship Series between the Phils and Astros, at the New York Times.

Also at the NYT is an Astros cheating scandal primer, by Neil Vigdor.

Baseball Photos of the Week:

Willie McCovey and Jim Bunning.

Don Drysdale, Tommy Davis and Sandy Koufax on “The Red Skelton Hour.”

Yankees’ Ralph Terry, with the Corvette given to him by Sport Magazine in recognition of his winning the outstanding performer of the 1962 World Series.

Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

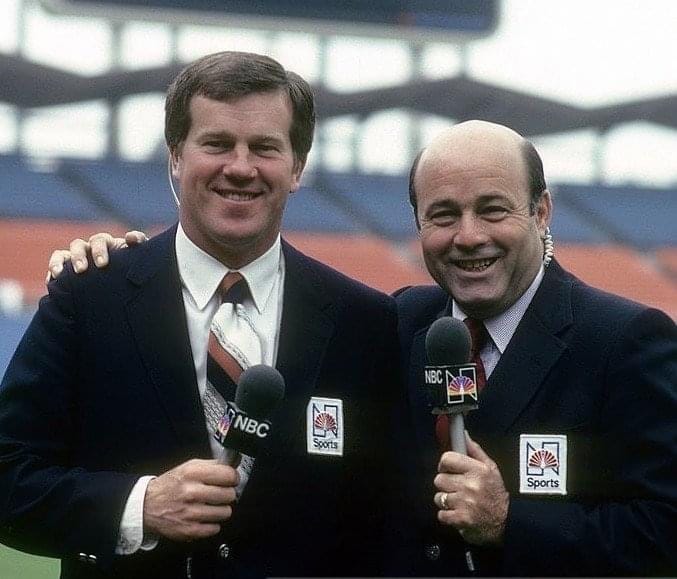

Tony Kubek and Joe Garagiola.

Genna Davis and Lori Petty in “A League or Their Own.”

Dodgers’ five men on the right side, circa 2014, which come Opening Day, 2023 will never be seen again.

Andrew Friedman look-alike in Ukraine.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Be friends with Howard on Facebook.

Read OBHC online here.