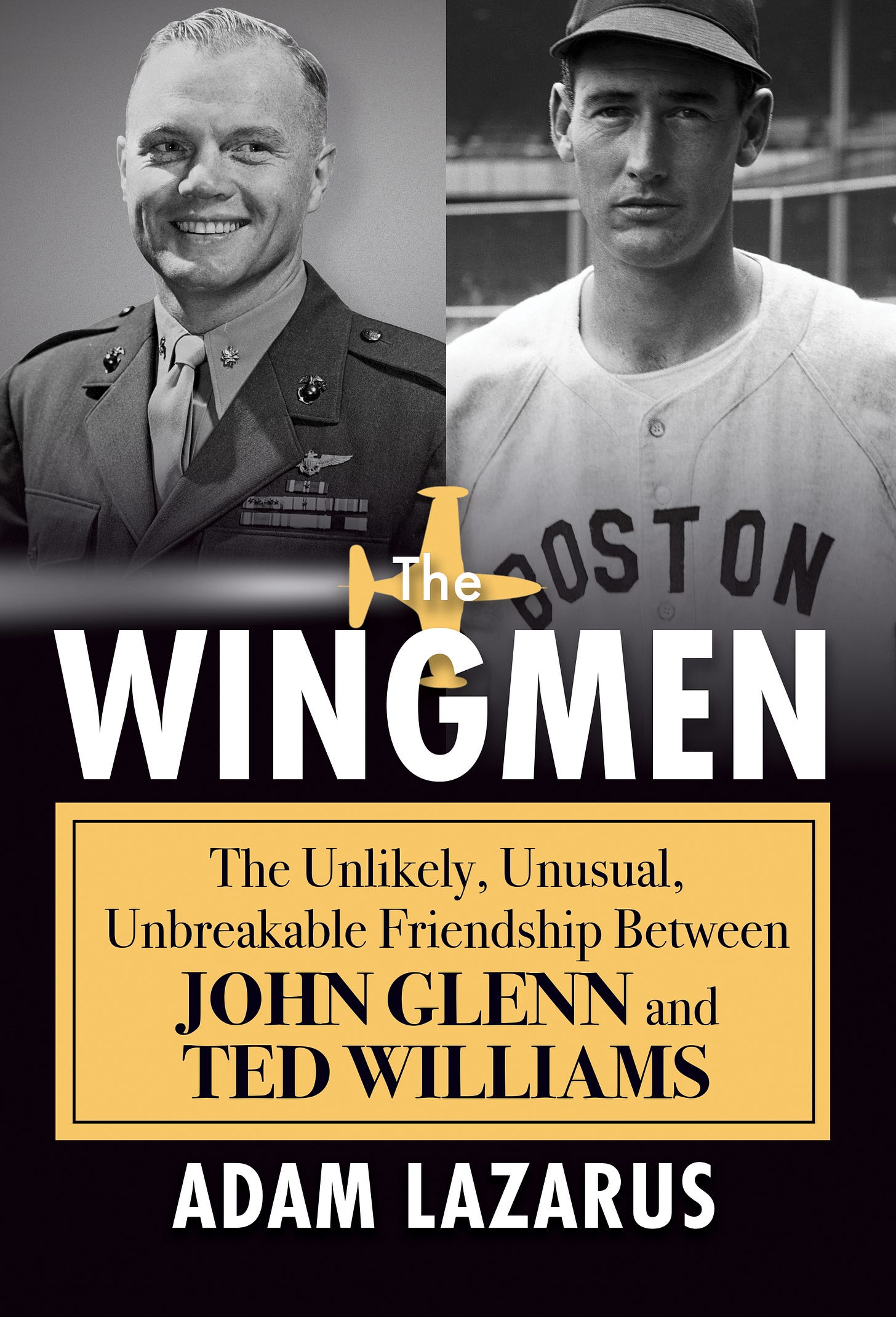

Book Excerpt: The Wingmen: The Unlikely, Unusual, Unbreakable Friendship Between John Glenn and Ted Williams

Plus ICYMI, Media Savvy and Baseball Photos of the Week.

There are history books and there are baseball books and on occasion the two shall meet. With number 22 in our book excerpt series, I am pleased to recommend one such example, and a fascinating one at that. It is “The Wingmen: The Unlikely, Unusual, Unbreakable Friendship Between John Glenn and Ted Williams,” by Adam Lazarus (Kensington Books, August 22, 2023, Hardcover $25.49).

Below please find Chapter Five: Hospitality, followed by the author’s bio and our usual weekly features.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter Five: Hospitality

“Everyone just counts the days till R&R in Japan” —Captain Bill Clem, letter home, February 13, 1953

Crash-landing a five-ton fireball at two hundred miles per hour took a lot out of Captain Ted Williams. Emotionally drained from nearly dying, physically drained from smashing around in a cramped, smoking cockpit and banging his feet on the useless pedals, and mentally drained from hours of debriefings, Williams just wanted something to eat when he returned to K-3.

“I remember Ted Williams coming out of the debriefing saying, ‘I AM STARVING!’” Woody Woodbury said. “They told him there was nothing to eat. He could get a candy bar.”

Hungry, but not gun-shy, Williams impressed 311’s executive officer Art Moran by saying he would like to fly again as soon as possible.

“That is the right attitude when one has had a narrow one: Get back in the air and don’t think about it,” Moran believed.

Twenty hours after bellying the plane in at K-13, Williams launched on an interdiction thirty miles northwest of Pyongyang. With 104 GPs and 1,995 rounds of ammunition Williams and the other nineteen pilots on Mission Number 3301 destroyed a Communist tank and infantry school then escaped to safety. Low on fuel, Williams again landed at K-13, refueled, and arrived at K-3. During a phone call with the United Press’s in-country war correspondent Victor Kendrick, Williams described the mission as, “all right, I guess, I couldn’t see very much up there.”

Two days later, he completed a run-of-the-mill bombing near the Taedong River, off the Kangso ward of Nampo. Immediately after Williams took off, Moran received a phone call. Major General Vernon Megee, the commanding officer of the entire First MAW, was irate.

“Moran, what in the hell are you doing down there?”

“Just trying to run a fighter squadron, General,” he answered.

“Did you launch Ted Williams again?”

“Yes sir.”

“Well for Christ’s sake, what if he gets shot down again? Think of the publicity.” “Down here, General, he is just another fighter pilot.”

Moran—as well as 311’s CO, Ken Coss, and MAG-33’s CO, Ben Robertshaw, both of whom flew with Williams on these two post-crash missions—seemed to have forgotten a Marine Corps policy stating that pilots who crashed were temporarily restricted from flying. When General Megee returned from K-8, he ordered Williams grounded for three days. But nearly six weeks would pass before he again squeezed his oversized frame into a Panther.

Williams had never shaken the virus he caught while training at Camp Pickel Meadows. In his first few weeks at K-3, he made frequent trips to the base’s infirmary for headaches, fever, clogged and congested ears, fluid leaking from his ears, and difficulty hearing. VMF-311 flight surgeon and Navy doctor Lieutenant (JG) George F. Catlett, Jr. diagnosed Williams as having bilateral aerotitis.

Catlett explained that flying fam hops and bombing missions in compressed air at twenty-five thousand feet—particularly his crash-landing at K-13—had only exacerbated his ailments. Catlett prescribed nasal decongestants, a prophylactic antibiotic (terramycin), and eventually a shot of penicillin. He also grounded Williams for a minimum of five days: regardless of his discomfort, a pilot unable to hear over radio was a liability to everyone in the air.

“I was really sick, the sickest I’ve been in my life,” he later wrote.

More than two weeks of rest didn’t show much improvement, and on March 12, Catlett ordered Williams to the naval hospital ship, the USS Consolation. Two days later a Marine helicopter transferred him to the USS Haven, which was docked near Inchon off the Yellow Sea. Upon his arrival, Williams was quartered with Nicholas A. Gandolfo, a ground infantry troop serving on the front lines with Company I of the Third Battalion for the First Marine Regiment. Sergeant Gandolfo had caught pneumonia while in the trenches atop the frigid Korean mountains. At one point his temperature reached 105 degrees.

“He wasn’t very happy because he didn’t want to be with the enlisted personnel,” recalled Gandolfo. “He wanted to move to better quarters. Well, he made such a stink they finally did move him to other quarters.”

Once transferred to an officer’s quarters, Williams enjoyed several amenities not offered to men like Sergeant Gandolfo. Enlisted personnel were housed three or four decks below, in crowded rooms with bunk beds, and had to wait in line for food at the ship’s mess hall. Officers enjoyed their own room with stewards who brought them far better quality meals.

Private First Class John Breske, a rifleman in Company E of the Second Battalion for the First Marine Regiment, also spent time aboard the Haven. Recuperating from severe grenade shrapnel wounds Breske heard the ship’s doctor refer to Williams as “the arrogant son of a . . .” during his daily rounds with patients.

Others aboard the ship found him charming. During Williams’s brief stay aboard the Consolation, both crew and patients clamored to catch a glimpse of the baseball star. Tony Ybarra, a 23-year-old Navy corpsman from Southern California, stopped by Williams’s bedside several times to keep him company.

“We were all interested, here we had a celebrity aboard the ship and we all wanted to go down and see him, and when we got a chance we did,” Ybarra remembered nearly seventy years later. “We talked mainly about why he was aboard the ship, what happened and all that. Not much about his career in baseball.”

While on the Haven, a Navy nurse named Nancy “Bing” Crosby monitored Williams’s ward and called him “the most gracious fellow . . . a neat guy.” He even agreed to pose for a few photographs with Crosby and the ship’s personnel.

Williams even granted an interview with Dick Hill, a radio correspondent for The Marine Corps Show which aired Friday nights on NBC. He initially refused, but Hill, who had flown in a helicopter then boarded a dinghy to reach the Haven, would not give up that easily. “Capt. Williams, I used to watch you play for the Minneapolis Millers,” he blurted out. Intrigued, Williams vetted Hill with an impromptu baseball trivia quiz about Teddy Ballgame’s minor-league playing career. Fortunately Hill had grown up in Minnesota and seen Williams play at the Millers’ Nicollet Park.

Wearing a hospital-issue robe, Williams chatted with Hill on the record in the ship’s social hall. Nasal, with a scratchy, weary voice, he talked of his illness, the recent crash-landing, and his fondness for catching up on baseball news via issues of Stars and Stripes. He accurately picked the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers to repeat as American and National League champions, respectively. Williams bristled at Hill’s question about his own baseball future.

“Well, I really don’t know, I have a tour of duty to perform over here before I think too much about what I’m going to do when I get out. However, I’m supposed to get out sometime in September/October and one of my first thoughts of course will be to get back to Florida. . . . It all depends how I feel.”

Although at first Williams had been constantly nauseated from a new antibiotic (aureomycin) prescribed by the Consolation’s physician, Lieutenant Harold W. Jayne, several weeks into his convalescence his symptoms subsided. He no longer felt “weak as a cat” and began walking around the ship, taking trips to the top deck to view Inchon Harbor. On one such tour through the often crowded, chaotic lower decks where loudspeakers frequently called out triage updates, Williams witnessed doctors operating on a young soldier hit in the face by shrapnel.

“They took a piece about the size of three-eighths of an inch thick out of this fellow’s head behind the eyes,” he wrote during his stay aboard the Haven. “I got a little woozy when they started using a drill to get into his brain. They did a beautiful job and today he’s not too bad.”

He took to visiting other sick patients—particularly enlisted men— and signed autographs. And he wrote so many letters that he joked about needing to have his arm put in a cast. A few went to Bill Churchman, his friend from Pensacola and Willow Grove. Once they arrived (often weeks later) back in the United States, Churchman casually mentioned the letters to the Boston Record’s Joe Cashman. He told Cashman that in addition to the pneumonia, Williams had become concerned about hearing loss as a result of his ears being clogged. Suddenly Churchman had become the press’s source for all news on Ted Williams’s health. Nearly every newspaper in the country soon reported that the hearing loss might lead to his relief from duty. Churchman told each reporter that Williams did not want a discharge, explaining that he “always wanted to finish first in everything.”

“It may be because of Ted’s desire to become an ace that he may cover up his ear trouble,” Churchman said. “Ted may not complain about it. He has great pride in what he wants to do and he may not say anything about his hearing difficulties.”

Pleased with the results of X-rays revealing clear lungs, Navy doctors deemed Williams fit for service again. Just as the fierce Korean winter started to tame, he returned to K-3 on April 1, and within three days was back in a Panther flying bombing missions across the MLR near Pyongyang.

After seven IDs in ten days Williams earned his first week of rest and recreation (R&R). Per the routine, a dozen or so officers went on leave in a rotation roughly every four weeks. Williams had been due for R&R in mid-March but missed his opportunity while aboard the Haven. Like all MAG-33 pilots, especially his friend Captain Bill Clem, Williams looked forward to several days in Japan, the designated R&R location for Marines serving in Korea.

On Tuesday, April 14, Williams, Clem, and a few other officers boarded a C-119, known as a “flying boxcar,” and flew 350 miles east to the Air Force base in Itami, located in the Osaka prefecture. Younger, unmarried officers and enlisted men on R&R—also known as “I&I, which is Intercourse and Intoxication”—enjoyed late nights in crowded bars or geisha houses. Williams chose more conventional tourist spots in the larger cities. He visited the Nishimura Lacquer factory, the Amita Damascene factory, and the Tatsumura Silk Mansion. Along the way he remembered his upcoming ninth wedding anniversary and purchased a gold-and-jade bracelet with matching earrings for Doris.

Near Osaka, Williams stopped by a cablegram office. Since leaving for Willow Grove the previous May, he claimed not to know much about the daily exploits of Major League Baseball, although he kept a copy of the latest sports almanac in his quarters at K-3. But by reading Stars and Stripes aboard the Haven, Williams had learned that on April 16 the Red Sox would open their 1953 season on the road against Philadelphia. To manager Lou Boudreau, Williams wired “Good luck in opener and best wishes to all—Ted Williams.” Prior to Boston’s 11−6 victory over the A’s, the cable was posted in the visitors’ clubhouse beneath Connie Mack Stadium.

While dazzled by the bright lights of the larger cities’ downtowns at night, Williams preferred quieter sites, such as Hirohito’s Hayama Imperial Villa overlooking Sagami Bay. He took dozens of Kodachrome and black-and-white photographs of the idyllic gardens and traditional Japanese architecture where General Douglas MacArthur had drafted Japan’s unconditional surrender of World War II. In Kyoto, for a few thousand yen—the conversion rate was roughly 360 yen to one U.S. dollar—he rented a room at the hillside Miyako Hotel, which overlooked the ancient city of roughly one million people. Known as the “shrine city” for its 1,429 Buddhist temples and 405 Shinto shrines, Kyoto offered Williams countless opportunities to snap more photographs.

More so than anything, he enjoyed the food, particularly the fresh shrimp and seafood. In Osaka he dined on “damn good steaks.” Something about the presentation of sukiyaki, a one-pot dish consisting of beef, vegetables, and noodles, turned him off and he refused to try it.

Six weeks later, Williams returned to Japan for his second leave. He dropped by a casino in Kobe that was populated with beautiful women and, in his words, “an Indian prince or something,” then visited towering Buddhist monuments in Nara.

John Glenn was on leave that week as well.

“I went on R&R to Japan with him once for a week and we had a great time. No comment on that,” Glenn teased a crowd, grinning as he said it, during a lecture at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in 2012.

Earlier in the spring, Glenn had also visited Japan. He stopped at several tourist spots, picked up silk samples and glassware brochures for Annie, but decided against purchasing a ninety-six-piece custom hand-painted Noritake china set that came with guaranteed shipping to the United States. He was thoroughly impressed by the country’s cleanliness and burgeoning industries—“[a] 100% change from China . . . tremendous progress”—as well as the efficiency of a train system that allowed him to see Itami, Tokyo, Yokosuka, Kyoto, Osaka, and Tokorozawa, all within a few days. But it was Ted Williams that impressed him the most.

For the most part during his stay in Japan, Williams avoided being recognized by fans and reporters, an impossibility if he visited restaurants, nightclubs, and tourist attractions in America. But Japan had become baseball-crazy beginning in 1934. That November a team of barnstorming major leaguers led by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig had played a series of games against local all-stars in front of huge crowds at the Koshien Stadium in Nishinomiya and Meiji Shrine Stadium in Tokyo.

A few days into his R&R, Williams’s anonymity ran out.

On the streets of Kyoto several MAG-33 officers, including Glenn and Williams, were touring the city. Along the way, they stopped to admire the scenery and take a few photographs. Dressed in green Service Alphas and garrison caps, the Americans already stood out. But Williams in particular caught the attention of a group of children gathered nearby. Whispering and pointing from afar, they thought they had spied the unmistakable physique and rugged face of a baseball legend. The children did not speak English, and neither Williams nor any of his Marine buddies spoke Japanese, but the two parties communicated.

The boldest child among the group stepped forward, fixed himself into a baseball batting stance, swung for the fences, then pointed directly at Williams, who let loose a distinctively loud, deep laugh. He nodded, acknowledging his identity.

Delighted by his discovery, the young Japanese boy swung again, but this time Williams furrowed his brow. He trotted over, spread the batter’s feet farther apart, bent him more at the waste, aligned his head properly, and cocked his arms back. Now satisfied with the boy’s stance, Williams walked sixty or so feet in the opposite direction. Toeing the mock pitching rubber, he arched into a windup, and threw the boy shadow batting practice.

“[The boy] swung with all his might,” John Glenn remembered. “Ted ducked, let out a whooshing, whooping big yell, swung around 180 degrees as though that non-existent baseball was headed for the center field bleachers. The kids were jumping up and down and no one was more surprised than the batter, and I’m sure he was an instant hero, but Ted got a bigger kick out of that than the kids did.”

For years John Glenn had known of Ted Williams the peerless baseball star. And during those early weeks of 1953, while they served together in VMF-311, Glenn knew Ted Williams the inexperienced, if not unlucky, Marine Corps fighter pilot. But on that day John Glenn, for the first time, saw Ted Williams the man: reclusive yet gregarious, a perfectionist yet accommodating.

Over the next five decades Glenn and Williams would share many similarly brief, yet memorable episodes together. Some born out of achievement or celebration, others out of relief or sheer luck, still others out of disappointment or even anger. But perhaps more than any other, the playful scene on the streets of Kyoto remained with Glenn. And with Williams as well.

“Nothing gave him more pleasure than talking in that inimitable booming voice of his about those Marine days in Korea,” Glenn recalled nearly fifty years later. “And he still remembered those kids in Kyoto.”

About the author:

Adam Lazarus is an author specializing in non-fiction books featuring iconic and compelling figures in American history.

Adam’s fifth book, The Wingmen: The Unlikely, Unusual, Unbreakable Friendship Between John Glenn and Ted Williams, was released in August 2023 and has received favorable reviews and mentions from outlets such as the New York Post, the Boston Globe, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist/ALA, and Publishers Weekly.

Previous books written by Adam include Chasing Greatness, Super Bowl Monday, Best of Rivals, and Hail to the Redskins: Gibbs, the Diesel, the Hogs, and the Glory Days of D.C.’s Football Dynasty.

His writing has also appeared in USA Today, ESPN the Magazine, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among other publications. He holds a bachelor’s degree in English from Kenyon College and a master’s degree in professional writing from Carnegie Mellon University. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia, with his wife, twin boys, and a variety of four-legged children (dogs).

ICYMI:

The times, they are a changin’. The Dodgers have gone from hording prospects to their detriment to actually moving some of them. First to go were starting pitcher Ryan Pepiot and outfielder Jonny DeLuca, who were shipped to Tampa Bay in the Tyler Glasnow trade in December. Last week Los Angeles dealt their 2023 Minor League Player of the Year Michael Busch, along with reliever Yency Almonte to the Cubs for a pair of young(er) players, starting pitcher Jackson Ferris and outfielder Zyhir Hope. Neither prospect will need to be placed on the 40-man roster. With the free-agent signing of Teoscar Hernandez earlier, the club now has one spot open on the 40-man.

L.A. has also signed right-hander Elieser Hernández, Brandon Davis and Chris Okey to minor-league deals. And they have inked baseball’s number 14 international prospect, shortstop Emil Morales.

In front office news, the Dodgers have brought back Raúl Ibañez as their vice president of baseball development and special projects, after a three-year absence.

Alex Anthopoulos, former Dodgers assistant general manager and current Braves president of baseball operations, has had his contract extended through the 2031 season.

Former Dodgers infielder and 2016 walkoff hero Charlie Culberson, 35, has signed a minor-league contract to pitch in the Atlanta organization. Below is the video of the division-winning homer, which is also Vin Scully’s final call.

Three months after unceremoniously passing over then-GM Kim Ng for their newly-created president of baseball operations position, the Marlins have hired Rachel Balkovec to be their director of player development. Ng was a Dodgers assistant GM under Ned Colletti.

I don’t like to write about these things as I always have, going all the way back to Bobby Cox, but alas I find it necessary. Here is the latest out of the Dominican Republic in the alleged-pedophile-and-Rays-shortstop Wander Franco case. And the latest in the Julio-Urias-domestic-violence case.

Media Savvy:

Former President of the Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco and current California Controller Malia M. Cohen would like the state to change its tax laws so that high-income earners like Shohei Ohtani cannot have salaries deferred to the extent that they are. By Bill Shaikin at the Los Angeles Times.

Former Reds’ first baseman and likely future Hall of Famer Joey Votto would like to continue playing into his forties. C. Trent Rosecrans has the story at the Athletic.

Also at the Athletic is a piece in which the baseball writers rationalize their Hall of Fame ballots. Or in the case of Daniel Brown, who voted for known performance enhancing drug cheaters Manny Ramirez, Alex Rodriguez and Gary Sheffield, don’t even bother to mention it.

From Aaron Rodgers one day to an Emmy scandal the next. The Worldwide Leader? Pfft!

Baseball Photos of the Week:

Mike Scioscia, Steve Garvey, Dodgers photographer Jon SooHoo, Bill Russell and Steve Sax. Photo by Mickey Hatcher

Willie Mays at the 1955 All-Star Game.

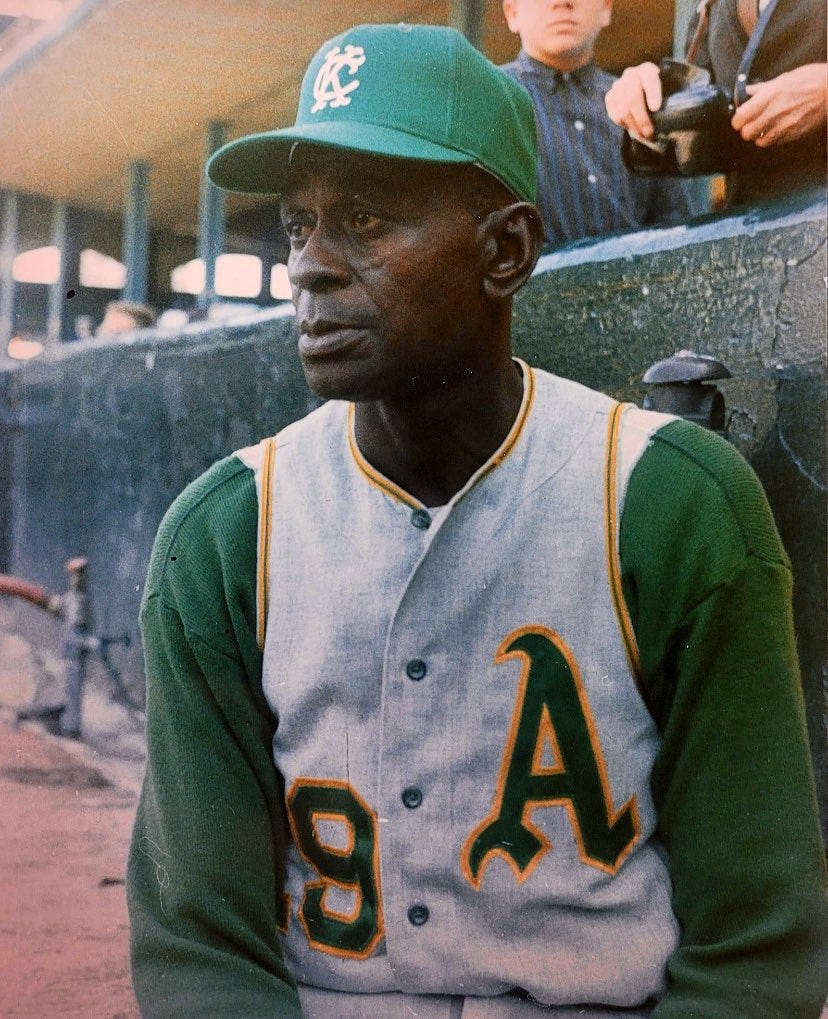

Satchel Paige.

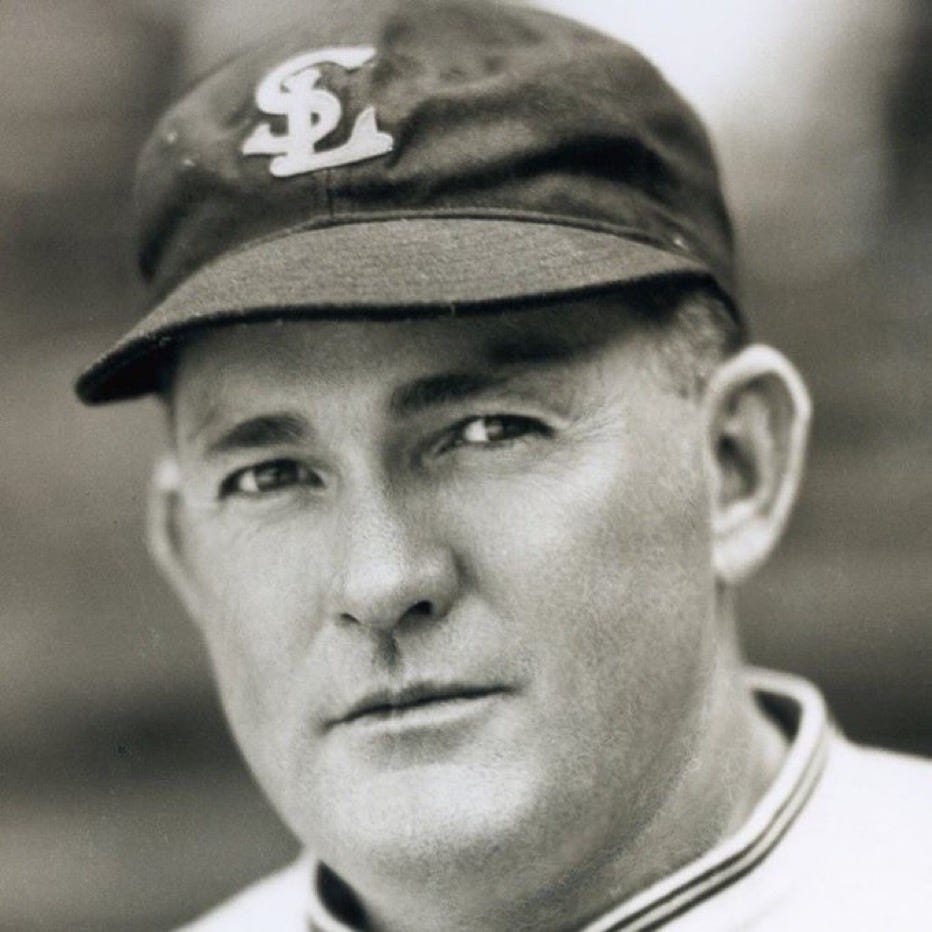

Rogers Hornsby.

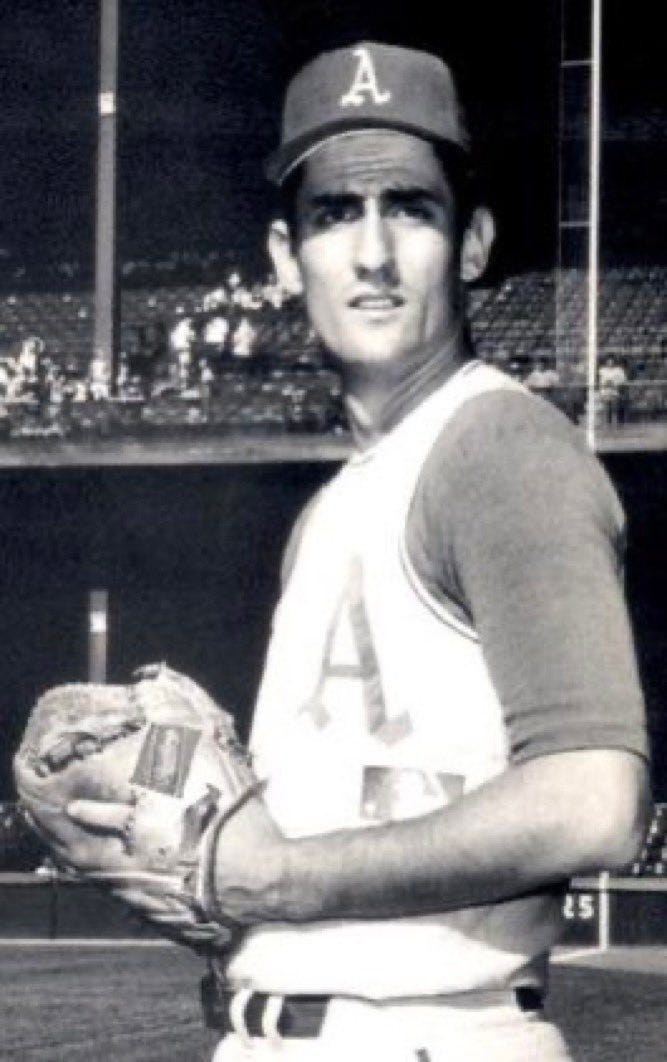

Tom Seaver.

Rollie Fingers.

From Pitching Ninja, Rob Friedman: “Needed a pic for a thumbnail, so asked AI to draw a left-handed hitter at bat from the pitcher’s perspective.”

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the Internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter. Follow OBHC on Twitter here. Read OBHC online here.