Excerpt: Diamond Duels: Baseball's Greatest Matchups

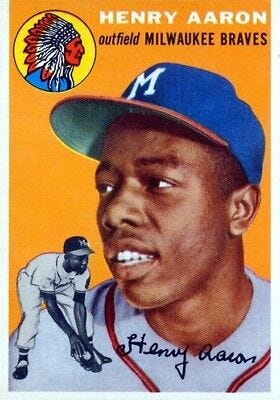

Chapter Four: Hank Aaron vs. Don Drysdale.

Picture yourself watching a game at home, or in the stands. It’s Yoshinobu Yamamoto versus Aaron Judge, or Walker Buehler vs. Alex Verdugo. If you’re quick enough, you can find their career matchup statistics before the duel. Or better yet, recall almost any time between 1950 and 2016, listening to Vin Scully tell a tale about a pair of all-time greats, with some memorable words sprinkled in: “That sounded high” or “it’s like trying to throw a lamb chop past a wolf.”

Now think Walter Johnson vs. Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson vs. Honus Wagner or Warren Spahn vs. Stan Musial. Or, say, a comparison between Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams.

Well, now there’s an entire book about such things, one which merits the Good Howard Seal of Approval. It is “Diamond Duels: Baseball's Greatest Matchups,” by John Nogowski, Lyons Press, March 4, 2025, Paperback $20.71.

If it wasn’t completely obvious, the subject matter you are about to read is Dodgers-related.

This is one in a series of occasional free posts. Please support Howard’s work by clicking the button below and becoming a paid subscriber.

Chapter 4: Hank Aaron vs. Don Drysdale: A Baseball Education

SOMETIMES THE GROAN IS AUDIBLE. SOMETIMES, YOU CAN JUST READ IT on the face of that right-handed hitter when they go to the bullpen and bring in—yes, a sidearmer.

It is difficult enough to stand in a batter’s box and try to hit. But when the ball appears to be coming from behind your head, a ball that seems to swoop in horizontally at your hands and move across the plate away from you at high speeds, no right-handed hitter wants to have to deal with that.

Typically, pitchers who don’t have the velocity or the stuff to make it throwing overhand will sometimes resort to a most devious way of delivering the baseball—sidearm. And it can work. One of my son’s former teammates, trying to make his high school team as a light-hitting infielder, ended up being cut. He transferred to my son’s high school, found out he could throw underarm—sort of an extreme sidearmer—and ended up having a glorious career pitching at Florida State as an ace reliever, even managing a brief spin in the minors.

There have been a number of very successful sidearmers in the major leagues over the years; pitchers like Dan Quisenberry, Kent Tekulve, Mike Myers, Brad Ziegler, Ted Abernathy, Gene Garber, and Joe Smith all made a nice living as relievers. But a sidearming starter, now that’s a different story.

When that sidearmer happens to be 6-foot-5, throws in the mid-90s, and possesses a mean streak as wide as the Mississippi River, you’d better hang loose once you step into the batter’s box.

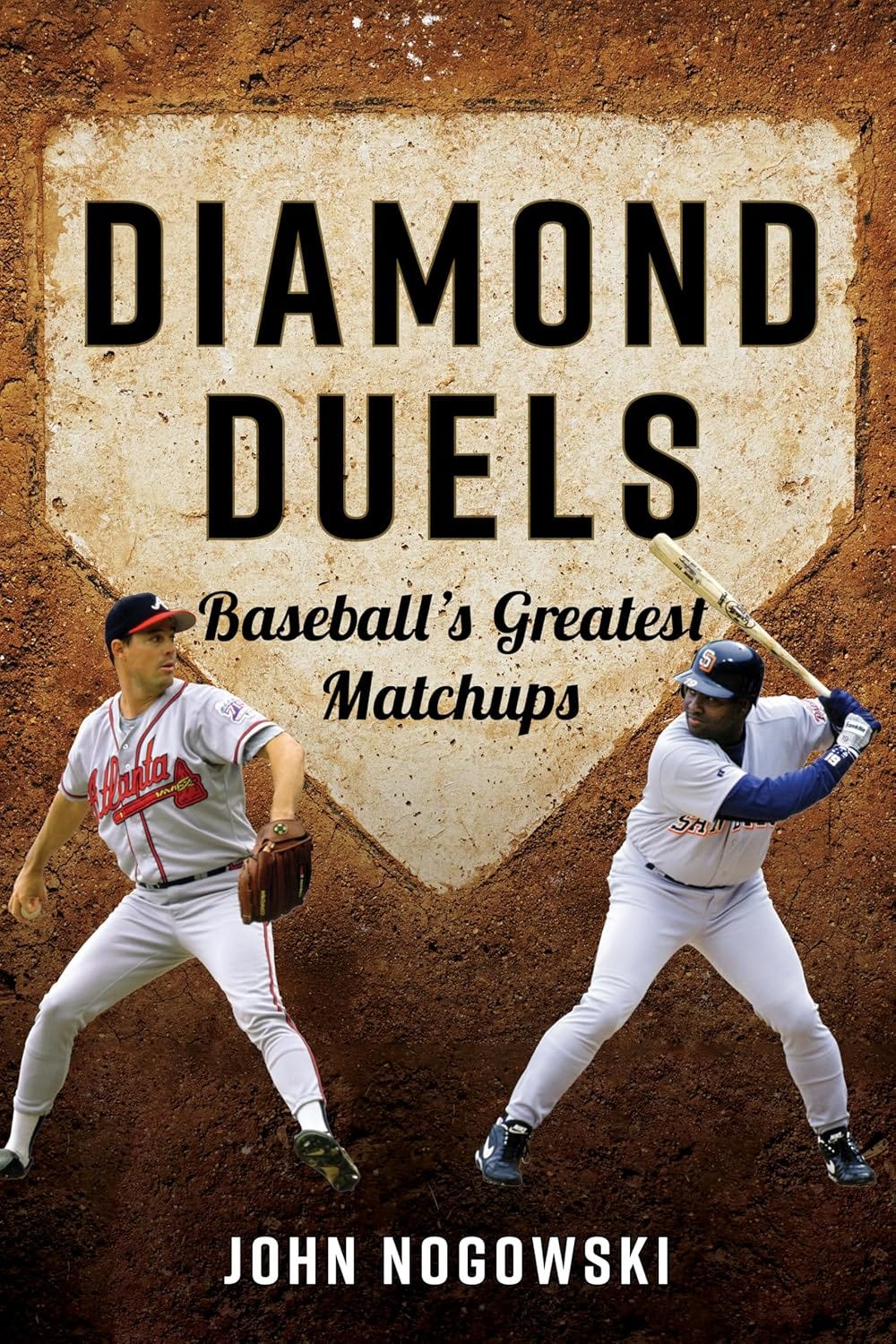

That was an accurate description of the late Los Angeles Dodgers Hall of Fame hurler Don Drysdale, an intimidating, sidearming slinger who led the National League in hit batters four consecutive years. Drysdale plunked 154 batters in his 14-year career, ranking him 20th on the all-time list. He’s probably at the very top on a per-inning basis. Almost all the current pitchers ahead of him on the all-time HBP list— Tim Wakefield, Randy Johnson, Charlie Hough, Charlie Morton, Jim Bunning, Roger Clemens, and Bert Blyleven—threw more career innings than Drysdale’s 3,432

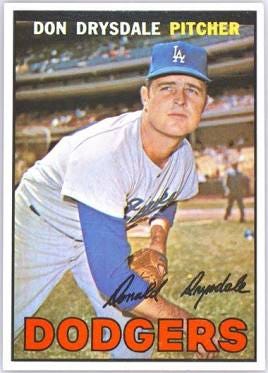

Enter Hank Aaron, a whippet-like right-handed hitter with a quick bat and an intense hatred of being thrown at. While it ended up that in 13 seasons and 249 at-bats facing Drysdale, Hank was never actually hit by a pitch, it wasn’t that Don didn’t try.

“I just feel that when you’re pitching, part of the plate has to be yours,” Drysdale told New York Times writer Dave Anderson some years after he retired. “The pitcher has to find out if the hitter is timid. And if the hitter is timid, he has to remind the hitter he’s timid.”

That was exactly the reminder Drysdale delivered to Aaron the first time he faced him in Drysdale’s rookie season. He smiled as he recounted the story to Anderson, telling him manager Walter Alston had given Drysdale, then a 19-year-old rookie, orders to throw at Aaron. Dodger pitching coach Sal Maglie, known as “The Barber” in his day for the close shaves he’d give enemy hitters, reiterated Alston’s point. One reason for Maglie’s insistence might have been this: Hank Aaron batted .409 against him, clubbing four homers. That might have been one of the factors that nudged Maglie into the ranks of coaches.

Anderson continues his column.

“‘Knock him down,’ spoke up Sal Maglie, ‘Knock him down.’ ‘No,’ said Roy Campanella. ‘If you knock him down, you’ll get him mad.’

‘Knock him down,’ Sal Maglie said. After the meeting, Sal Maglie told Don Drysdale, ‘Look over at me when Aaron comes up.’ And when the rookie right‐hander glanced into the dugout, Sal the barber nodded.

‘That was his sign,’ Don Drysdale recalled with smile. ‘I knocked him down. And after a curveball strike looked over again and Sal nodded again. And down he went again.’”

Aaron wound up rapping into a double play. Drysdale’s intimidating delivery made an impression and as the next season began, Drysdale continued knocking him down. A troubled Aaron went 1-for-18 for the season. Drysdale was, as the players say, “in his dome.”

In Aaron’s book I Had a Hammer, written with Lonnie Wheeler, former Braves publicity director Bob Allen remembered it well.

“‘One game Don Drysdale threw at Hank a time or two, and Hank went down,’ Allen explained. ‘He complained about it after the game, which was rare, because Hank never complained about much. We had a staff meeting the next day, and I can remember John Quinn saying, ‘Well, we’ve got a great young hitter in Hank. Now we’ll find out if he can stay in the league. It will depend on how he gets back after being knocked down like that.’”

Make no mistake, Aaron knew how he handled this would be important for the rest of his career. If other pitchers saw there was a way to get Hank out, things could get ugly and dangerous. His stay in the big leagues would be over fast.

“Of all the guys who threw inside, Drysdale did it the most effectively,” Aaron said. “God, Drysdale was rough. He would as soon knock you down as strike you out, and he was big and threw hard and came from the side—it seemed like he let the ball go about a foot from your ear. Drysdale was so rough on me that I thought he was going to put me out of the league—not by hitting me, just by making me look bad.”

Indeed, while Drysdale never actually hit Aaron, he didn’t have to. The intimidation factor was already there. He fanned Aaron 47 times, way more than Hank struck out against anyone else.

You could call it “Drysdale Dread.” Dodgers catcher Johnny Roseboro recognized what a weapon it was and in calling pitches, he worked out a good plan.

“With an 0-2 count, Drysdale would come sidearm inside with a 96 mph,” Roseboro said. “and when the hitter saw me move my glove inside, his intestinal fortitude will not let the batter look outside. So many a time Drysdale would just throw that ball on the outside corner—strike three.”

Aaron knew he had to figure this pitcher out. And pronto.

“I batted so poorly against Drysdale at first that Fred Haney, our manager at the time, was going to bench me one day when he pitched,” Aaron recalled. “Back then, sitting on the bench for a day wasn’t like it is now. Now, with the guaranteed contracts and diluted rosters, guys are happy to get the day off. But back then, nobody wanted to come out of the lineup, because there was always somebody eager to take your place. I said, “Mr. Haney, you just let me play against him today. I can’t sit on the bench. I’ve got to play. Drysdale got me the first couple of times that day—struck me out and made me look bad—and then I got a couple of hits. The last one was a bloop double that won the ball game. From that day on, I hit Drysdale.”

Sure enough, Aaron would figure him out. After that 1-for-18 in 1957, Drysdale began the 1958 season by retiring Hank seven more times, so the great Aaron was actually just 1-for-23 against the guy!

But an Aaron mini-breakthrough on June 6, a pair of singles, was a sign that things were about to change. The key was to get the bat head out. Even if the ball came from the side, if the bat head was there to meet it, that would work.

Three weeks later, on a beautiful Sunday afternoon at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, the Braves roughed up Dodger starter Stan Williams, knocking him out early. On in relief was Don Drysdale. So when Aaron stepped into the batter’s box against big #53 in the sixth inning, the bases were loaded with nobody out. Time for Hank to strike back.

John Nogowski is also the author of “Last Time Out: Big-League Farewells of Baseball’s Greats,” which we featured in 2022. Read an excerpt of that one here.

Aaron lined Drysdale’s first pitch over the right field fence for a grand slam, his first home run off the sidearmer and the first of Aaron’s career-high 17 homers off Drysdale. Hank, by the way, wound up with 16 grand slams, eighth all-time, tied with Dave Kingman and some guy named Ruth.

By the time 1958 came to a close, Aaron had two more singles and three doubles off Drysdale. He wasn’t sweating him anymore, hitting .320 against him for the year.

In 1959, Aaron—not particularly known at the time as a home-run threat—collected four homers off Drysdale, the most he hit off a pitcher in a single season, hitting .300. He hit three more off him in 1960, bat ting .318. Nobody would believe there was that 1-for-23 stretch now.

Hall of Famer Drysdale turned the tide back in his favor the next two seasons, holding Aaron to a .250 mark in 1961 (4-16 with three doubles, one home run) and an amazing 0-for-14 in 1962 which included three strikeouts in Aaron’s last five at-bats against him. Drysdale must have thought he had finally turned the tide. He had Aaron figured out once again.

Nope. “Bad Henry” bounced back with a stunning 1963, clubbing Drysdale’s offerings to the tune of .471 with eight doubles, four more homers, eight RBIs, his single best season against the sidearmer.

From there, it was back and forth between the two. Drysdale held Aaron down in 1964 (.176 in 1964 with no home runs allowed) and in 1965 (.222, one homer). Then it was Hank’s turn—.368 in 1966 with a pair of dingers, and .375 in 1968.

In between, Drysdale held Hank to .231 in 1967, only allowing a pair of singles with four whiffs. But the last time Aaron faced him that year, September 3, he took him deep for the 17th and final time. From there, Drysdale’s career began winding down. He and Aaron faced one another just 11 more times over his final two seasons; Aaron had three singles, three walks, one intentional, no RBIs. The fireworks were over.

In 1969, Drysdale lost his last start against the Braves. He got Aaron to pop out his first at-bat, then walked him and was chased from the start one batter later, allowing an RBI single to Rico Carty.

Plagued by rotator cuff problems, Drysdale made just five more starts that season, retiring on August 11, quite a ways from the finish line.

Like a lot of National League hitters, Aaron wasn’t disappointed to see him leave. When he looked back in Hammer, he remembered just what a challenge facing Drysdale was.

“In fact, when it was all over,” Aaron recalled, “I’d hit more home runs against Drysdale—17—than I had against any other pitcher. We had a great rivalry going, and there was nothing bitter about it.

“Later, when Claude Osteen was pitching for the Dodgers—I hit 14 home runs against Osteen—Drysdale used to call him before the Dodgers played the Braves and give him a little pep talk, tell him to bear down and give me a few more home runs so the Big D could get his name off the books.

“There are some people who thought Drysdale didn’t deserve to be elected into the Hall of Fame because he barely won 200 games (209), but I don’t agree. Anybody who batted against him knows he was one of the dominant pitchers of his day.”

When he sat down with Dave Anderson, Drysdale remembered Aaron, too.

“I wonder,” Drysdale told Anderson with a chuckle, “how many more than 17 he would have hit if I hadn’t pitched him inside. But the thing that Sal always told me about the knockdown pitch was, ‘It’s not the first one, it’s the second one.’ The second one makes the hitter know you meant the first one. And if you’ve got control, you can waste a pitch to put a little fear in the hitter.”

HANK AT THE PLATE

In a strange way, Hank Aaron’s career seemed to separate halfway through it. For the first half, he was seen as a soft-spoken, ruthlessly efficient offensive player. You never heard much about his defense, you never heard much about his baserunning. You just knew at the end of every season, you could look among the National League batting leaders and you’d see his name.

He won two batting titles (.328 in 1956, .355 in 1959), led the National League in home runs and RBIs four times each, but he never hit more than 47 in a season. He swatted 44 homers—his uniform number—four times.

It wasn’t until later on, when Aaron’s remarkable consistency got his home-run totals mounting, that we started to see him in a different light—Hank Aaron, the home-run threat.

He hit his 500th home run off the Giants’ Mike McCormick in July 1968, got number 600 off another Giant, Gaylord Perry, in April 1971, and number 700 in July 1973 off Ken Brett of the Phillies. He was steaming along toward Babe Ruth’s 714, hitting 40 home runs that season at age 39.000

To add to the drama, Aaron hit his 40th home run of the season off Houston’s Jerry Reuss in the fifth inning of the next-to-last game on the schedule, a homer which gave him 713 for his career, one shy of Ruth. Could he do it to end 1973 with a bang?

The answer turned out to be “No.” He managed a single off Larry Dierker in the seventh and the next day, with 40,517 on hand in Atlanta to see if he could tie Ruth, Aaron managed three hits but no homers. He singled off Dave Roberts in the first, fourth, and sixth, but no home runs.

The closest he got to a homer was in his final at-bat of the season against Houston fireballer Don Wilson, who gave Hank a lot of trouble (.147). Facing Wilson in the eighth, Aaron popped the ball in the air all the way out to second base. The Braves ended up as 5–3 losers and all of baseball had to wait for the 1974 season to see if Aaron could tie and then pass The Babe.

It sure didn’t take long. In his very first at-bat of the season against the Reds’ Jack Billingham, he launched a three-run homer to tie the Babe. He passed Ruth days later with a fourth-inning home run off Al Downing. He went on to hit 40 more home runs in his career, retiring after the 1976 season when he had returned to Milwaukee, this time to play for the Brewers. He finished with 755 home runs, tops of all time until Barry Bonds came along.

WHO HE HIT, WHO HE DIDN’T

One sure sign that things were different in Aaron’s day is looking at the list of pitchers he faced. There were 20 different pitchers that Hank faced over 100 times. So he knew what they threw and they knew him.

Of those starters, he had the most trouble—like a lot of National League hitters—with the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson and the Mets’ Tom Seaver. Gibson held Aaron to a .215 average, fanning him 32 times, surrendering eight homers. Seaver held him to .205 with four homers. But facing the best of the rest of NL starters in his era—here are 14 of ’em—you can see Hank did pretty darn well:

Dick Ellsworth (.451, 6 homers)

Johnny Antonelli (.409, 8 homers)

Larry Jackson (.363, 9 homers)

Sandy Koufax (.362, 7 homers)

Don Cardwell (.361, 10 homers)

Harvey Haddix (.358, 8 homers)

Bob Friend (.348, 12 homers)

Roger Craig (.347, 10 homers)

Bob Purkey (.308, 4 homers)

Chris Short (.304, 5 homers)

Gaylord Perry (.294, 3 homers)

Robin Roberts (.291, 9 homers)

Juan Marichal (.288, 8 homers)

Vern Law (.280, 8 homers)

Claude Osteen (.262, 14 homers)

The bottom line was this: Aaron was a machine. And if you’ve followed baseball for a while, you know how streaky the game can be. Aaron was a model of consistency.

For his career, Aaron hit .318 against lefties, .298 vs. righties, .304 at home, .306 on the road and monthly, he was a metronome—.297 in April, .298 in May, .305 in June, .310 in July, .310 in August, .307 in September/October.

When you sustain numbers like those over a 23-year career against the best in the game, hey, that’s an amazing achievement.

Yes, there were a few pitchers that gave him a hard time. Jim Brosnan (.160) and Don Wilson (.147, mentioned above) were tough for him. Aaron also struggled with Dave Giusti (.213), Al McBean (.167), Jim Brewer (.179), Bob Bruce (.175), and Bill Stoneman (.194).

But for every one of those, there was a Tug McGraw (.444 with four homers in 27 at-bats) or Don Gullett (.462 with seven homers in 26 at-bats) or Don Elston (.472 with four homers in 36 at-bats) to boost that batting average right back up.

As people look back on Aaron’s career, one of the lasting impressions of the player was his unflappable manner. Well, after he solved Drysdale. Nothing seemed to rattle him. And the way he handled things left people in awe.

Allen reflected on this in Hammer:

“Later on, of course, Hank made a career out of hitting Drysdale. I used to drive all around the state with Hank going to speaking engagements, and one time in the car I asked him why he never talked about hitting—about the way he hit Drysdale and everybody else. I’ll never forget what he said. He said, ‘If you can do it, you don’t have to talk about it.’ That’s just the way he was.”

Yet he knew what he was capable of and he knew where he stood. Some of his contemporaries such as Willie Mays, Bob Gibson, Pete Rose, and Johnny Bench might have gotten more publicity than he did, but Hank knew what he had done and how he measured up against the greats in the history of the game.

It might have taken him a few years but in Hammer, Hank finally spoke his piece about the player that seemed to draw most of those headlines in his day, the great Willie Mays.

“I considered Mays a rival, certainly, but a friendly rival,” Aaron said, firmly. “At the same time, I would never accept the position as second best. I looked at Willie as my guideline. There were certain things that I couldn’t do as well as he could, but I felt if I could do some things a little better, I should and maybe would be classified as the same type of ballplayer. I’ve never seen a better all-around ballplayer than Willie Mays, but I will say this: Willie was not as good a hitter as I was. No way.”

Their final numbers:

Willie Mays: .301 AVG., 660 HR, 1,909 RBI

Hank Aaron: .305 AVG., 755 HR, 2,297 RBI

You tell ’em, Hank. You tell ’em.

About the author:

John Nogowski is an award-winning sports writer and teaches AP Language, English and Journalism at Gadsden County High School in Havana, Florida. He is the author of Last Time Out: Big League Farewells of Baseball’s Greats (Lyons Press, 2022). He lives in Tallahassee, FL.

And remember, glove conquers all.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the internet since Y2K. Follow him on Bluesky. And Twitter. Read OBHC online here.

I wonder what the numbers would be if they had played in each other’s ballparks all those years.

Good, juicy article but I wish there was more on Drysdale.